Alan Hassenfeld, the former chairman and CEO of one of the state’s largest companies, Hasbro Inc., isn’t buying the conventional wisdom on municipal bankruptcy, that it is a tarnish worth avoiding at all costs.

“I think we’re in deeper trouble in Providence than anyone comprehends,” Hassenfeld told Providence Business News. “I’m not sure if we shouldn’t pull a Detroit or Central Falls and level the playing field, and start all over.”

His comments in a wide-ranging interview in December may have startled some people, given the relatively positive outlook of Mayor Jorge O. Elorza, but not everyone.

The reality is that Providence has structural problems that have presented challenges for a succession of city leaders. Bankruptcy, also known as receivership, hasn’t been seen as a sound option by most elected officials who have fought to improve the city’s finances, including Elorza. The second-year mayor will present his fiscal 2017 budget this spring and has said this is the year residents and business leaders will again see “cranes in the sky” in Providence.

But the specter of the drastic step of bankruptcy to help the capital city reset its finances has hung in the shadows of City Hall since 2011, when tiny Central Falls became the first Rhode Island municipality to go through the process.

Four years ago, Robert Flanders Jr., then the state-appointed receiver for Central Falls, said he expected Providence would follow suit. It didn’t, as then-Mayor Angel Taveras instead curbed expenses by negotiating reductions with employee unions, and increased revenue by eliciting larger contributions from the city’s biggest nonprofit entities.

Nevertheless, the city if anything is in worse financial shape today, insisted Flanders, who is a partner at the Providence law firm Hinckley Allen & Snyder LLP.

“Things have definitely gotten worse,” Flanders said. “What happened in 2013 was the then-mayor hoisted the ‘mission accomplished’ banner. He really failed to deal with the fundamental restructuring that was needed to solve the problem. In my view, he made a few cosmetic changes that didn’t solve the problem and handed it off to his successor.”

Elorza, like Taveras before him, doesn’t share Flanders’ gloomy view.

“There’s a lot of barroom talk about how Providence is going into bankruptcy, etcetera,” Elorza told PBN. “We definitely have our fiscal challenges but we don’t have any challenges we can’t figure out and overcome.”

But as recently as the most recent mayoral campaign, whether Providence should enter receivership was raised as an issue. Since then, the city’s financial stability has come under question publicly in actions taken by national bond-rating services, as well as the ongoing turmoil initiated by Elorza’s attempt to cut firefighter overtime by moving the department schedule to a rotation of larger, but fewer, platoons.

Beyond City Hall, the financial status of Providence became a question for panelists at last month’s annual Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce legislative luncheon. And it found its way into the 2016 Outlook published by commercial real estate firm CB Richard Ellis New England, which observed that despite signs of promise and potential: “A word of caution for 2016 is the tenuous nature of the city of Providence’s financial condition, which needs to be resolved.”

HOW BAD IS IT?

So how bad is it, exactly?

For five of the past seven fiscal years, the state’s capital city has operated at a deficit, Moody’s Investors Service summarized in November, before downgrading its financial outlook. Another bond-rating service, Fitch Ratings, in February lowered the rating for the city one notch.

Even with recent improvement in the state economy, Providence continued last year to spend more money than it took in.

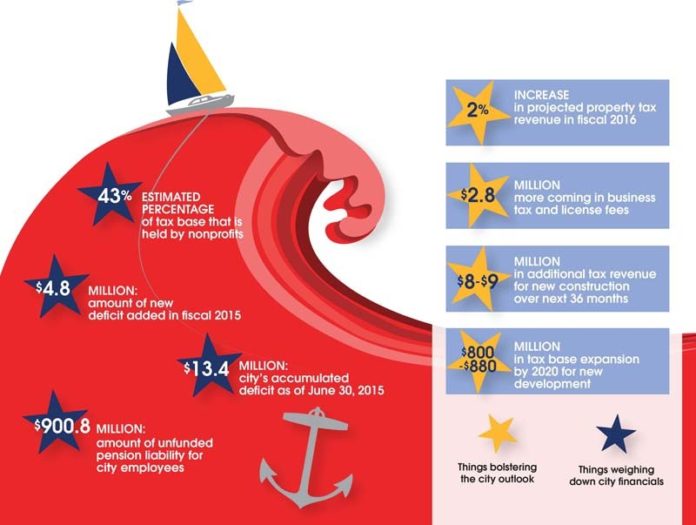

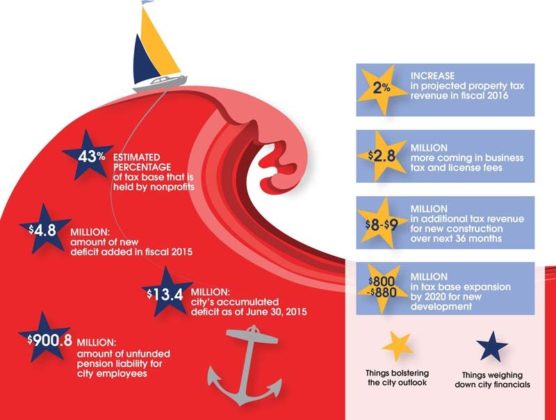

The cumulative deficit carried by the city grew in fiscal 2015, the year that ended in June, to $13 million, according to its annual financial reporting. This past year, the city added nearly $4.8 million to the operating deficit.

Meanwhile, the unfunded liability for employee pensions is approaching $1 billion, having grown from $873 million to $901 million for the year that ended in June, according to the annual audit.

The most immediate issue, the reversal of a two-year pattern of progress in not adding to the accumulated deficit, sparked a letter in October from the state auditor general. The latter is tasked with overseeing compliance with a state law that requires cities with multiyear deficits to pay them off within five years. The city recently agreed to a renewed schedule of repayments, starting with $4.3 million this year.

Why can’t the city get its financial affairs in order?

The reasons for the accumulated deficits cited by economists, auditors and bond-rating services hit familiar chords: revenue constrained by little tax base growth, overcome by expenses that are growing with increased health care and employee-related costs.

The fiscal challenges also are rooted in demographics and city characteristics that haven’t helped Providence rebound from the national recession.

The city population, which has grown modestly over 20 years, is growing more impoverished. And its labor force, largely unionized, represents a growing expense that is difficult to cut because wages and benefits are covered by contracts.

Flanders said the experience of Central Falls is evidence that the bankruptcy process can be beneficial. For Providence, it would mean a fresh start, he said, including a shedding of what he called “legacy problems,” including generous cost-of-living adjustments that in some cases date to the administration of the late Mayor Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci Jr.

In municipal bankruptcy, a judge cannot compel the city to increase taxes, or to sell its assets, Flanders said.

“To some people, bankruptcy is a four-letter word. It’s the stigma that’s allegedly associated with it,” he said. “But if you look at Central Falls, [it] is now on the rebound. The reality is most of the fallouts from declaring bankruptcy have already occurred. Property values are suppressed. Business doesn’t want to locate in a city where the fiscal house is not in order. Nobody wants to be a part of a place where there is constant pressure to raise taxes.”

Taveras, contacted by PBN, declined to be interviewed. But in a statement he had provided to several news outlets last October, after the city’s $4.8 million fiscal deficit was reported, Taveras defended his record, saying he left Providence “better off than it was when I became mayor.”

“Running a city like Providence is difficult,” Taveras wrote. “The choices an administration makes on a daily basis certainly have a significant and immediate impact on city finances and our future. The Elorza administration should focus on the choices it has made since taking office to find the reasons for the [$4.8 million] deficit that has appeared in the last few months.”

Elorza, a former law school professor who also holds an accounting degree, said he immediately commissioned an analysis of the long-term and short-term financial status of the city, on taking office in January 2015. Inspired by its conclusion, which found the city’s structural deficit could balloon to a cumulative $85 million by 2022, he made a series of decisions. Among them was the move last spring to reorganize firefighter work schedules.

The savings will be $5 million annually beginning in fiscal 2017, Elorza said.

The ramifications of the decision to take on the union are being closely followed by business leaders.

Nothing has inspired the recent talk of bankruptcy more than the prospect of another huge bill, a potential multimillion dollar back payment to the city’s firefighters. The latter argue they have been unfairly compensated in the switch to the new schedule that has increased their weekly work hours.

Arbitrators assigned by the Rhode Island Superior Court will decide whether Providence will have to reimburse the firefighters for hours worked as defined under their contract or, as Elorza contends, whether the reorganization is a management prerogative. In a recent public meeting, the City Council’s auditor pointedly observed that nothing has been set aside to cover a payment, if the decision goes against the administration.

‘COLOSSAL MISTAKE’

How much is at stake? The firefighters’ union estimates it is owed $8 million to $9 million for pay dating back to the switch made on Aug. 2. The decision to alter the rate of pay, work hours and shift structure was made unilaterally by the mayor, in violation of the contract, according to Paul A. Doughty, president of Local 799 International Association of Firefighters. The union represents about 400 firefighters, emergency medical-services employees and battalion chiefs.

“This was a colossal mistake,” Doughty said.

Under the contract, he said, the firefighters are to be paid overtime for every hour worked beyond 42 hours a week. The new schedule has the union members working 56 hours a week.

The administration has sought, so far unsuccessfully, to have the lawsuits dismissed. Prior to the lawsuits, efforts at mediation also failed.

For Doughty, the issue is centered on fairness. Firefighters may be redeployed under a new schedule by management right. But the resulting pay differential has to be addressed. “What you can’t do is make me work more hours and not pay me more,” he said.

For Flanders, who supports the process of bankruptcy as an avenue for the city, the dispute is another example of a legacy problem. Under municipal bankruptcy, the employee contracts would no longer be recognized, said Flanders, a former Rhode Island Supreme Court justice.

Just as Taveras, now practicing law in Boston, encountered what he called a “Category 5” fiscal hurricane shortly after entering the mayor’s office, Elorza has said the fiscal year that reflected the $4.8 million deficit came under a budget created by his predecessor.

On assuming office, Elorza said, he encountered almost $20 million in what he termed “budget risk.” He refinanced some of the city’s debt, a one-time move that saved about $8 million.

In other decisions, he opted to not pursue the sale of city property, as recommended by Taveras. Elorza instead scuttled plans to sell the former Flynn Middle School and would not sign a long-term lease extension for the city-owned Triggs Memorial Golf Course. Together they represented about $4 million in lost savings, which would have covered most of the eventual operating deficit. But Elorza said they weren’t good deals for the city, and would have continued the dubious practice of reliance on temporary fixes to balance the budget.

“I could have ended up with a balanced or very close to a balanced budget,” he said. “I chose not to because that would have been a bad deal for the city. We’re not relying on these one-time fixes anymore. There’s only so much we can sell and these are bad deals for the city we’re just not going to subject ourselves to.”

To bolster city revenue under the fiscal 2016 budget, his first, Elorza attached new fees on equipment at the Port of Providence that are expected to produce $500,000 annually. The city is converting old coin-fed parking meters to those that accept credit cards, and anticipates a modest increase in revenue with the addition of several hundred new metered spaces in business areas, according to the most recent financial report.

The administration also raised fees for building permits and business licenses, purchased back its streetlights from National Grid, a move that Elorza expects will reap $15 million in savings over the next decade, and renegotiated the contract for the Roger Williams Park Zoo, which will generate $9.5 million over the next 20 years.

Some of the greatest expectations in the administration rest with property values. The fiscal 2016 budget, which ends June 30, included an expectation of 2 percent growth in the city’s tax base.

In the upcoming fiscal year, Elorza said the current revaluation of all city property, the first since the recession ended, is expected to boost property tax revenue even more. “We know where the real estate market is now as opposed to three years ago. We expect to see an increase in revenue.”

One ramification of the city’s descent into deficit operation in fiscal 2015 is additional oversight by the state. The office of the state auditor will have periodic meetings with the administration to ensure that the city’s plan for deficit repayment remains on track, according to Dennis E. Hoyle, Rhode Island auditor general.

In addition, two bond-rating agencies also have recently downgraded either the city’s bond rating, or its financial outlook. Moody’s in November adjusted the outlook for Providence ratings to “negative,” citing the then-unaudited results that showed a return to deficit operations.

In early February, Fitch Ratings downgraded the city’s bond rating for two bond issues one notch, to BBB negative, citing constrained revenue and increased costs, including unfunded pension liabilities.

NO PANACEA

For some observers, a potential upside to bankruptcy would be a fresh start for Providence, a chance to renegotiate some of the benefits and salaries that pressure its budget.

When asked how often the subject of bankruptcy and Providence comes up in conversation, John Simmons, executive director of the nonprofit Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council, said bluntly: “Every day.”

“Every day I hear people concerned about the long-term viability and financing of Providence,” Simmons said.

In a report RIPEC prepared in 2012, as several cities in Rhode Island teetered financially, the think tank advised bankruptcy was not a panacea. In the case of Providence, it has unusual status within Rhode Island as the capital city and the center of commerce. It isn’t Central Falls, Simmons said.

Nevertheless, the city has considerable risk in the ongoing challenge of the firefighter compensation, he said.

Would it be better for the city to enter bankruptcy, in an effort to shed debt and compel the renegotiation of employee contracts, which annually drive the expense side of the budget? It’s an unanswerable question, Simmons said.

“The question is, what would the bankruptcy provide for the city?” he said. “There’s a positive side. It could restructure its debt, its contractual agreements. It would make sense for Providence only for that purpose, but not the long-term issue, which is a balancing. You have a harder time when you’re trying to promote Providence to businesses to come here, for the predictability and stability of your government and tax structure.”

Alden Anderson, senior vice president at CB Richard Ellis New England, said companies do evaluate the city tax system and governance as part of their due diligence.

“We regularly talk to investors looking at opportunities in and around the Providence area and the subject of predictability of property taxes and services is regularly asked,” Anderson said. “It’s certainly something that is on investors’ minds.”

He would not say how he views bankruptcy, but said the city leadership needs to be able to explain how they will provide a predictable and stable atmosphere for investment. “I’m very sympathetic to the city’s leadership. It’s not an easy thing to solve,” he said.

Providence, in particular, has some unique challenges compared to other cities, according to economist Leonard Lardaro, a professor at the University of Rhode Island. He cited the expense of the city’s pension system, and other fixed costs, which leave little room for budget maneuvering.

Of concern more recently, he said, is the slowing of the economy in Rhode Island.

“Some of the overhead is just strangling them,” he said. “Times have been fairly good for the whole state, and still [Providence is] struggling. That’s the bad news. If things go downhill, how is it going to get better for them?”

The last time Providence was in similar financial straits was in 2012, after several years of a national and regional recession prompted the state to make drastic cuts in aid payments. Providence saw plummeting real estate values, as well as increasing unemployment.

Between 2008 and 2012, state aid to local communities in Rhode Island fell by 73 percent, according to a report by RIPEC. Those cuts came as property tax collections were hampered by declining values.

Besides Central Falls, East Providence, Providence and Woonsocket all struggled with substantial deficits. Both East Providence and Woonsocket eventually sought assistance through state oversight. Both have since emerged from the process. Central Falls exited bankruptcy a little over a year after it filed, having reached agreement on cuts that included a 55 percent reduction in retiree pensions.

Elorza’s predecessor, Taveras, through several months in 2012 led efforts to downscale Providence spending.

The cuts under his administration would eventually include reductions in retiree benefits, including a 10-year freeze on cost-of-living allowances. Taveras would eventually close four schools and lay off nonunionized employees. Taveras also moved employees who were 65 or older to Medicare for health insurance, rather than the city’s own self-insured plan. The shift drew a legal challenge that remains active among selected employee groups.

His administration also renegotiated existing agreements with the city’s major nonprofits, including Brown University, Lifespan Inc. and others, which resulted in millions more in increased contributions to the host city.

But City Council President Luis Aponte says the city remains at a financial disadvantage in its relationship with nonprofits.

“We are above 43 percent of our entire tax base being untaxable and that continues to grow,” he said. “It’s incumbent on the state to reimburse the city somewhat for those lost revenues.”

As for the talk of bankruptcy, Aponte said it would have a chilling effect on development.

“How much viability do you think there will continue to be for the I-195 land in a city that is in bankruptcy or considering bankruptcy? That sort of instability is not what a developer or an investor would want,” he said.

Elorza is optimistic the city will regain its financial footing. In his first State of the City address, in February, he emphasized the potential for more than $500 million in investment in the city, through projects that are expected to begin in 2016.

The city recently was awarded a grant to prepare a 10-year plan for attracting investment. “What this comes down to is we have long-term fiscal challenges,” Elorza said. “We have to face them head on. … That’s exactly what we’re focusing on.” •