(Editor’s note: This is the first of a three-part series exploring the progress of East Providence’s 10-year effort to redevelop its waterfront and what it might mean for a similar effort underway in Providence.)

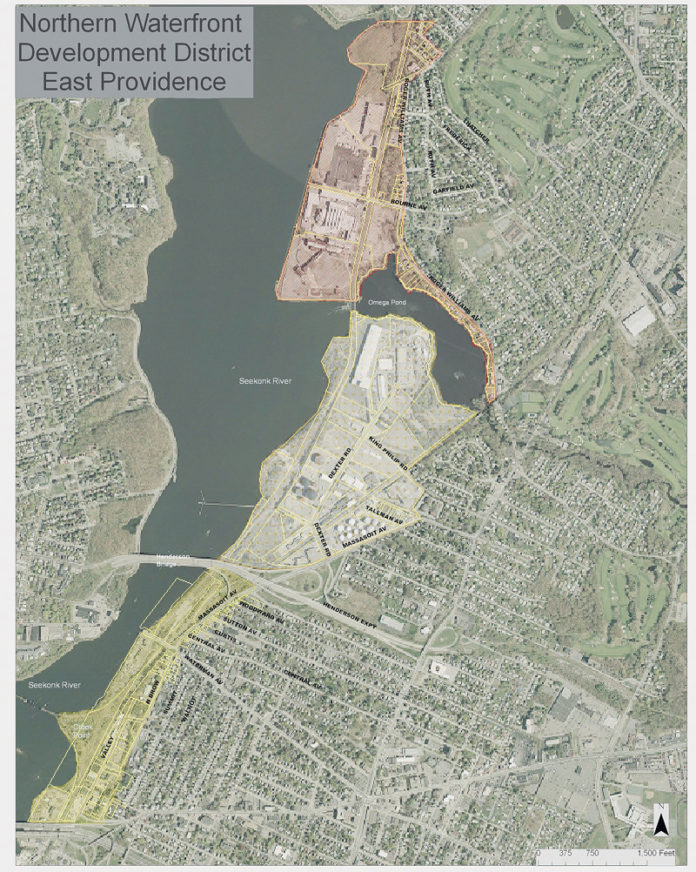

By the end of the 20th century one of East Providence’s greatest assets, roughly 300 acres of ship-and rail-accessible, industrial land along the Providence and Seekonk rivers, had become one of its biggest liabilities.

The factories and fuel depots that once thrived along the waterfront were struggling, shut down or gone, in many cases leaving decades of chemical contamination in the soil.

Looking to the future, city leaders saw growth potential in technology, retailing and condominiums and wanted to find a way to reposition their fallow industrial land to take advantage of those markets. But it wasn’t going to be easy. With so many engineering, regulatory, infrastructure and environmental challenges, private developers eyed the area warily despite its saltwater views and proximity to downtown Providence.

So with other large, multipiece redevelopment projects in mind, such as the Capital Center in Providence and the Quonset Business Park in North Kingstown, East Providence created its own state-supported, special-planning entity to manage development within the waterfront district. With enabling legislation put forward by then-state Senate President William V. Irons, who lived in the city’s Rumford neighborhood, the East Providence Waterfront District Commission was created in the summer of 2003 and soon completed a master plan for the 7-mile coastline.

In pitching the plan, city officials estimated that waterfront redevelopment would add 2 million square feet of new commercial space, 2,500 new homes and $1 billion to the tax base in 10 years.

Now a decade later, the commission has seen significant progress in some areas of the waterfront, although it hasn’t come close to matching those early plans.

Of the total 300 acres in the district, approximately 55 acres have been redeveloped so far in six separate projects. That acreage would more than double, to 117 acres, if two large residential projects, Kettle Point and Village on the Waterfront, now planned and permitted off Veterans Memorial Parkway, are built.

Of course, considering the redevelopment project was interrupted by the collapse of the housing market and subsequent financial crisis, some would say having anything built was a major accomplishment. The commission has also had to maintain continuity while the city, due to near insolvency, has been under control of a state budget commission since 2011.

“I think we have done a lot in 10 years,” said Jeanne Boyle, East Providence planning director and executive director of the Waterfront Commission. “It is an asset of statewide importance. We have had some projects that received permits and not gone forward, but a number of properties that were vacant have been redeveloped.”

The Waterfront Commission was designed as a one-stop shop for local permitting, capable of speeding a developer, typically within 45 days, to city approval.

But state officials from the R.I. Department of Transportation, R.I. Economic Development Corporation and R.I. Department of Environmental Management also have seats on the commission, which means once a project has its local permits, it already has a head start on getting state sign-offs, crucial considering the environmental issues of many sites.

“Our biggest accomplishment is we have awakened private interest in a tremendous asset,” said William Fazioli, who is chairman of the commission and was city manager when it was formed.

In addition to permitting, the commission also offers tax-increment financing packages and up to $75,000 in federal loans for energy retrofits.

The first project completed under the commission process was the 54-unit Ross Commons condominium complex, by Peregrine Group and Kirkbrae Properties in Rumford.

But after that three of the next four projects were commercial renovations in the former Fram complex at 10 New Road and Pawtucket Avenue, an area tucked away from public view and not directly on the waterfront.

“Tockwotton made a huge difference because people saw that beautiful building and saw what was possible on the waterfront,” Boyle said.

And that momentum on the high-visibility land south of I-195 appears to have continued.

For the past year Chevron has been doing site-preparation work for the Village on the Waterfront project, and after receiving commission approval this summer, Kettle Point could potentially be breaking ground this fall.

While they didn’t draw as much attention as the big residential projects, Waterfront Commission officials say the Pawtucket Avenue commercial projects in the northern waterfront shouldn’t be underestimated.

The first to open in 2008 was a new $30 million 140,000 square-foot factory for Aspen Aerogels, which makes insulation using nanotechnology.

Then, starting in 2009 with a second phase completed last year, Wurth Baer Supply Co. built a new 100,000-square-foot distribution center providing materials to the woodworking industry.

Also last year, SkyZone opened a 25,000-square-foot indoor trampoline park in another part of the complex.

And not long after the commission’s 10-year anniversary this fall, Eaton Aerospace Group is expected to relocate 200 aerospace workers now in Warwick, plus add another 50 employees, to a 145,000-square-foot plant in half of the old Fram complex.

For Eaton, whose old plant by the Pawtuxet River was damaged in the 2010 floods, the commission helped secure $5 million in federal assistance for flood victims.

As an example of the kind of revenue potential of waterfront redevelopment, Fazioli said East Providence collected $100,000 in back taxes, which may have never been paid, on the property Eaton is renovating, plus $100,000 in permitting fees. The Tockwotton Home generated nearly $200,000 in permitting fees.

The first section of the new Waterfront Drive, between Warren Avenue and Dexter Road, was finished last year for $6.6 million. Eventually, the road is expected to run nearly the length of the waterfront district, from Village on the Waterfront to Beverage Hill Avenue in Pawtucket.

The commission is hoping the opening of the new road ignites interest in what has been the most challenging part of the waterfront district to spur development, the area between Rumford and I-195.

With the real estate market fully inflated in 2006, New York-based Geo-Nova won approval to turn the 27-acre, former Washburn Wire/Ocean State Steel site in the Phillipsdale neighborhood into a 500-unit, urban village with shops, offices, public park and marina.

When the bubble burst, so did Geo-Nova’s plans and no projects have even been proposed in Phillipsdale since.

Looking back at the last 10 years, both Boyle and Fazioli said there was nothing they think the commission could have done differently – such as having the city acquire more properties – to have accelerated investment.

“There was never an appetite for city owned,” Fazioli said. “In my opinion, I have faith in the capital markets and private use of capital.”

Peregrine Group Principal Colin Kane, who worked with the commission on Ross Commons and now is chairman of the I-195 Redevelopment District Commission, has spoken with Boyle about lessons from East Providence that could apply to Providence’s former highway lands.

Mostly the I-195 Commission will look at what East Providence has done with permitting, Kane said. The two commissions differ substantially, he said, in that the I-195 entity owns the 20 acres it hopes to develop and will be active in deciding what is built.

“What does apply to us is having approvals in one super-permitting agency,” Kane said. “The difference is [East Providence] doesn’t own the land – they are truly responding to market conditions,” he said. •