Few plot twists sound more cruel or ominous for small, independent cinemas than the death of film.

Hollywood’s decision to abandon the grainy flicker of celluloid for the computerized clarity of digital images is inflicting steep costs on art houses and drive-ins across the country, many already barely scraping by thanks to home cinema and the Internet.

By the end of the year, movie studios say they will stop making the 35 millimeter prints that motion pictures have been shown on for a century, forcing theaters to invest in new digital projectors or go dark.

In New England, small theaters without the revenue to buy new digital systems, which can cost upwards of $100,000, are turning to their customers and Internet fundraising for help.

Following in the footsteps of the Brattle Theater in Cambridge, Mass., and the Jane Pickens Theater in Newport, Cable Car Cinema in Providence launched a successful online fundraising campaign on the website Kickstarter.com to buy a new projector.

Needing $48,500 for the conversion, by the end of March 681 Cable Car supporters had come through with $54,581.

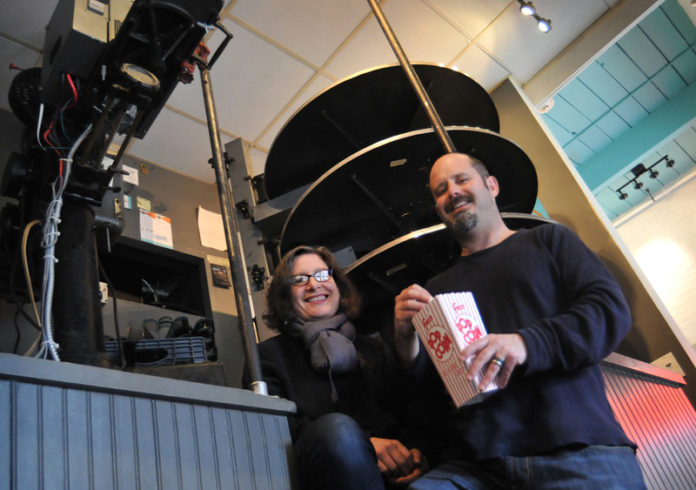

“For us it would have been cost-prohibitive,” said Cable Car co-owner Daniel Julius Kamil about the prospect of switching to digital without donations. “We are tapped out from the renovation we did in 2010 and our own finances are deep in here.”

Kamil’s wife and theater co-owner, Emily Steffian, said the campaign also served as a kind of referendum on the business’ importance to the community.

“If they care we will find out and if not we will find that out too,” Steffian said before the campaign was completed.

The move away from film toward digital has been in the works for years and affects most theaters around the world.

From the movie studios’ perspective, the switch is difficult to argue with.

Instead of having hundreds of physical prints of each film developed, at a cost of several thousand dollars each, then shipped in canisters to theaters around the world, digital movies are uploaded and sent to theaters on a computer hard drive.

Kamil said last year a Massachusetts company called FilmTrans that had delivered prints to theaters throughout the region abruptly folded when it became clear they had no future in the digital transition.

How much the switch costs each theater depends on the size of the operation and how much besides the projector, such as the sound system, needs to be changed.

Kamil said until recently digital projectors have all cost around $100,000, but new models for use in smaller theaters have brought the price down to the $50,000 to $60,000 mark.

The 75-year-old Avon Cinema in Providence is also preparing to make the switch to digital.

Avon co-owner Richard Dulgarian said his theater will finance its transition without asking for donations, and he expects to pay somewhere around $80,000 to complete the project.

“It’s something we have to do and, I don’t want to disrespect the others, but I think it is something theaters have a responsibility to pay for ourselves,” Dulgarian said.

Like many art-house-theater owners, Dulgarian hasn’t been in a hurry to make the switch and is bittersweet about abandoning film as an aesthetic choice.

“I am told my picture will be brighter and sharper, and the sound will be better, and I will benefit,” Dulgarian said. “But I like 35 millimeter and have not seen enough digital to make a comparison.”

“It might be the difference between a compact disc and vinyl records,” he added, using the analogy most connected to the switch. “The slight graininess to the film stock is something I am used to but might not be missed.”

As a sign of his attachment to his old projector, a hulking, mid-century piece with chrome and curves, Dulgarian said he is going to keep the unit around just in case.

Perhaps a bigger concern, and not just at small, independent cinemas, is what happens to projectionists, who aren’t needed to spool reels and monitor the picture anymore. With digital, entire multiplex programs could be run from a laptop in an office block.

Dulgarian said the Avon has eight part-time projectionists and he has offered to keep them on to do other tasks at the theater, but none have expressed any interest.

“It’s sad – I usually have the most in common with them,” Dulgarian said about the projectionists. “I will probably keep them on at least for a transitional period, because even with digital someone has to be around in case something goes wrong.”

Jane Pickens owner Kathy Staab noted that the theater, which she took over in 2001, has been a part of each major technical evolution in cinema, from silent films to talkies, reel-to-reel to platters, and now digital.

In a nod to history, Jane Pickens is showing “Singing in the Rain,” about the silent film transition to sound, and “Cinema Paradiso,” about the friendship between a boy and a projectionist.

“We have gone through all the different changes over the years as technology has shifted and this is the next stage in the evolution,” Staab said.

Staab said the two projectionists at the Jane Pickens have other jobs that support them and told her they will be alright without the part-time work.

At the Cable Car, Kamil said he will keep the theater’s four projectionists employed in other roles. The cinema has added beer and wine, and its café now accounts for 60 percent of revenue.

Not having to pay projectionists should save cash-strapped theaters some money, as will the lower shipping costs of a hard drive compared with film canisters.

But Kamil at the Cable Car expects most of the savings from digital conversion will stay with the movie studios, which will keep charging theaters the same amount for each film.

With so many entertainment choices available thanks to streaming video and services such as Netflix, Kamil said independent cinemas have had to diversify offerings – many are expanding live performances – and offer things people are unlikely to see elsewhere.

“One of the things we are fortunate for is, because our revenue streams are diversified, we can take more programmatic risks like documentaries, music, and a range of subject matter, from art to politics, that would not run in a major theater,” Kamil said. •