As small-business owners clambered to get in on the federal payroll relief program launched in the wake of COVID-19, Anna Mangeni held back.

Her business, Nissi Naturals LLC, was in trouble, having lost all its retail and event-related sales when stay-at-home orders took effect in mid-March. But applying through a bank, as the program required, was an automatic “no” for Mangeni.

“I’ve been through the banks, and it was not a good process,” she said.

First, it was a higher interest rate on the mortgage she and her husband took out compared with peers with a similar credit history. Since launching the natural skin and hair care product company in 2015, they have repeatedly faced rejection or inflated interest on lines of credit by banks.

Mangeni attributed her bad banking experiences in part to her race; she is Black.

[caption id="attachment_337022" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

UNFAIR TREATMENT: Nissi Naturals co-owners Andrew and Anna Mangeni are pictured with the their son Samuel. Despite losing all retail and event-related sales when stay-at-home orders were implemented in mid-March due to COVID-19, the natural hair and skin care products store did not apply for a federal Paycheck Protection Program loan because Anna Mangeni says the company has been treated unfairly by the banks in the past. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

The lack of existing banking relationships is among the reasons cited for why minority-owned businesses have been largely left out – rejected or ineligible – for the billions of dollars in federal relief programs. The New York Times reported in May that 12% of Black and Latino business owners who applied for U.S. Small Business Administration funding received it, compared with 38% of small businesses overall. Nearly half of the Black- and Latino-owned businesses surveyed anticipated closing permanently in the next six months.

Yet minority-owned businesses, among the most vulnerable during and before the pandemic, were identified in a January report commissioned by the state as crucial to Rhode Island’s economic future, their success benefiting not only people of color but all workers, residents and taxpayers.

And the racial-justice reckoning set off after George Floyd, a Black man, died while in police custody in Minneapolis in May has created what some consider to be a unique opportunity to level a long-unequal playing field for minority business owners.

“This is a tiered system which has not achieved its potential over the last 50 years,” said Bruce Katz, an economic consultant who has studied the impact of systemic racism on minority-owned businesses across the country, including in Rhode Island. Katz called the current spotlight on race issues one with a “transformative effect” for equity in all areas, including business.

Black-owned businesses nationwide have reported surging revenue in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. That heightened awareness among consumers can also translate to awareness – along with funding and policies – among the institutions that support businesses, according to Sean Rogers, associate professor of human resources and labor relations at the University of Rhode Island.

“It has the potential to create this kind of virtuous cycle of funding support, consumer awareness and business that really buttresses these organizations for a longer period of time into the future,” Rogers said.

But whether this potential will indeed become reality, Rogers is unsure – it’s too soon to tell if the social upheaval will have a lasting impact, or fade just as quickly as it began, he said.

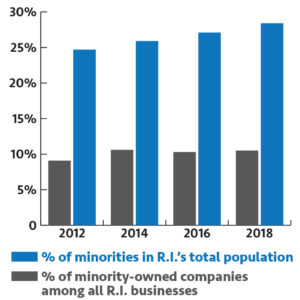

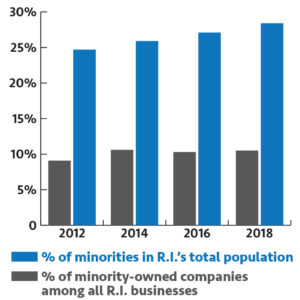

In the economic report commissioned by R.I. Commerce Corp., Katz highlighted inequalities in the state’s business community, noting that the share of businesses owned by racial and ethnic minorities is far less than their share of the state’s general population.

Data collected by the R.I. Department of Labor and Training and the U.S. Census Bureau corroborates that finding. In 2018, the most recent year available, minorities comprised 28.4% of the state’s 1.1 million people, a nearly 4 percentage point increase over 2012’s numbers despite relatively flat overall population growth. The state’s share of minority-owned businesses, however, rose just 1.4 percentage points in that same period, from 9.1% of businesses in 2012 to 10.5% in 2018.

DOUBLING DOWN

It’s a problem that reverberates across the country, and the region, with people of color comprising as little as 2.7% of business owners in Vermont and Maine and the region-high of 15.1% in Connecticut, according to 2018 census data. Rhode Island ranks third in the region for the percentage of minority-owned businesses.

While Rhode Island is not alone in its underrepresentation of minorities in the business community, its small size and well-established systems make it more able to address disparities than other states, Katz said.

The report recommended creating an accelerator for minority-owned businesses modeled after an established, privately funded program in Cincinnati, to help minority entrepreneurs start and build their businesses through training, mentorship and funding access.

But a new program may not be the answer, according to Kelly Ramirez, CEO of Social Enterprise Greenhouse. Ramirez said the problem is an issue of communication and coordination.

“Our early experience shows there are a lot of business owners and entrepreneurs who are just not connected to all the support that exists,” Ramirez said.

The organization has doubled down on diversity and inclusion in its programs, opening offices in Pawtucket and Newport and launching new programs – including a Spanish-language incubator – to serve a long-excluded segment of the business community.

[caption id="attachment_337024" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PREPARED: Graduates hold their certificates after completing Social Enterprise Greenhouse’s new incubator program designed for Spanish-speaking entrepreneurs in the Central Falls area. From 2017 to 2019, SEG has more than doubled the number of minority entrepreneurs served through its programs to 120. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

SEG has also tried to be more creative in its outreach to eligible participants – going door to door in neighborhoods, using Facebook and advertising on Latino radio stations.

Oscar Mejias, CEO of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, agreed that officials need to use nontraditional methods to reach minority entrepreneurs.

“If SEG or Commerce RI have a new program, they go to [TV news] or The Providence Journal, and Latinos don’t read The Providence Journal,” Mejias said.

Data suggests SEG’s strategy is working; from 2017 to 2019, SEG has more than doubled the number of minority entrepreneurs served through its programs from 55 to 120.

Among the success stories touted by SEG is Eugenio Fernandez Jr., who launched Asthenis Pharmacy in Providence in 2018 with the help of a $12,500 SEG loan.

The Cranston Street storefront is not your typical pharmacy. There are no aisles of products, no register-side candy – offering junk food seems contrary to filling prescriptions for patients with high cholesterol and diabetes, Fernandez said.

The small back room of prescriptions is the way he finances the company, but the true purpose is community health education, particularly for the lower-income and Spanish-speaking population in his neighborhood. That mission has become more important during the COVID-19 pandemic, as Fernandez worked to relay updates to his community about state testing, wearing masks, symptoms of the virus and more.

A graduate of the University of Rhode Island and Harvard University with master’s degrees in pharmacy, business and population health, Fernandez acknowledged that his training and connections made starting a business easier. He noted the inherent disadvantages faced by communities of color in any endeavor, including starting a business, and supports programming to mitigate those hardships.

OUT OF THE LOOP?

That Fernandez works in health services might have also helped. Support and funding for technology and health care companies are more developed than for food-service and hospitality industries, although the latter represents a major part of the state economy, according to Katz’s report for Rhode Island Commerce.

Rhode Island minority-owned businesses comprised 5% or less of the manufacturing, professional services, science and technology industries, according to the Census Bureau’s 2016 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs. In contrast, minority-owned businesses made up more than 27% of the accommodation and food-service industries. The latter industry has been hit particularly hard by forced closures and economic slowdowns due to the new coronavirus, which might also mean disproportionately adverse effects for the minority business community, Mejias said.

[caption id="attachment_337023" align="alignleft" width="300"]

UNEQUAL GROWTH

While nonwhites are becoming a larger part

of Rhode Island’s overall population, the

percentage of minority-owned businesses has remained relatively flat in recent years.

/ SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau;

R.I. Department of Labor and Training[/caption]

One area where traditionally underserved industry sectors might expect to find support and money is government contracting.

The R.I. Department of Administration, through its Office of Diversity, Equity and Opportunity, works to partner with minority-owned small businesses on government procurements, weighting their applications higher and requiring that 10% of total dollars be awarded to minority- or women-owned businesses, according to Dorinda L. Keene, assistant administrator for minority business enterprise compliance.

In 2014, minority- and women-owned businesses comprised 4.3% of participation – equal to $36.2 million – in state procurements. By fiscal 2018, participation rose to 14.7%, or $103.7 million, well above the state’s 10% minimum requirement. The state continued to exceed the 10% threshold in fiscal 2019, the most recent year available, with 13.1% participation and a record-high $104.9 million in contracts awarded, according to ODEO.

Still, some have criticized the absence of minority contractors in the $34 million the state poured into building emergency field hospitals for a potential COVID-19 surge. The Rhode Island Black Business Association recently faulted the state for not complying with its own requirements, calling for removal of a waiver policy that exempts contractors from meeting requirements to seek out minority business enterprises as long as the contractors demonstrate “good-faith efforts.”

In response to recent criticism by RIBBA and state lawmakers, Keene, who also serves as ODEO acting associate director, reiterated the state’s commitment to inclusion, including through an in-progress study that aims to identify and eliminate barriers to minority-owned business participation.

“We are committed to working with all stakeholders to improve access and support for MBEs in Rhode Island,” Keene said in an email.

She did not comment on the waiver policy.

“What we’re really seeing is a knee on the neck of businesses that strangles the economic efforts of our community,” said Sen. Harold M. Metz, D-Providence. “The stranglehold that has kept us back for so long needs to be removed.”

Ron Brewer, vice president of C.C. Business Corp., agrees with Metz. The Providence company, which offers professional security and janitorial services, has never been awarded a state contract in the 20 years it’s been registered in Rhode Island as a Black-owned business.

“It shows that Rhode Island is one of those states where it’s who you know,” Brewer said. “Everybody turned to their buddies … and those are not minority people.”

It’s the kind of subtle racism the company has experienced for decades, Brewer said. He recalled how a Providence private school initially expressed interest in contracting with his company for security services, but after meeting face to face – seeing that the company’s leaders were Black – the school backed out.

C.C. Business Corp. is not hurting for business – its contract with Thundermist Health Center’s multiple Rhode Island locations has continued to bring in money, as well as jobs from new customers seeking extra security in the wake of a night of riots and looting in Providence. It also received a Paycheck Protection Program loan.

Instead, the company’s biggest struggle is hiring, having lost several workers due to fear of exposure to the coronavirus on the job, and others who were “not a good fit.”

While careful to distinguish security from policing, both jobs require a committed, even-keeled kind of temperament, Brewer said. His work, as well as his 20 years of service in the U.S. Army, give Brewer a unique lens through which to view police violence toward people of color.

In some situations, Brewer empathized with difficult, split-second decisions facing police officers in dangerous circumstances. On the other hand, he had no tolerance for unnecessary use of force with peaceful protesters.

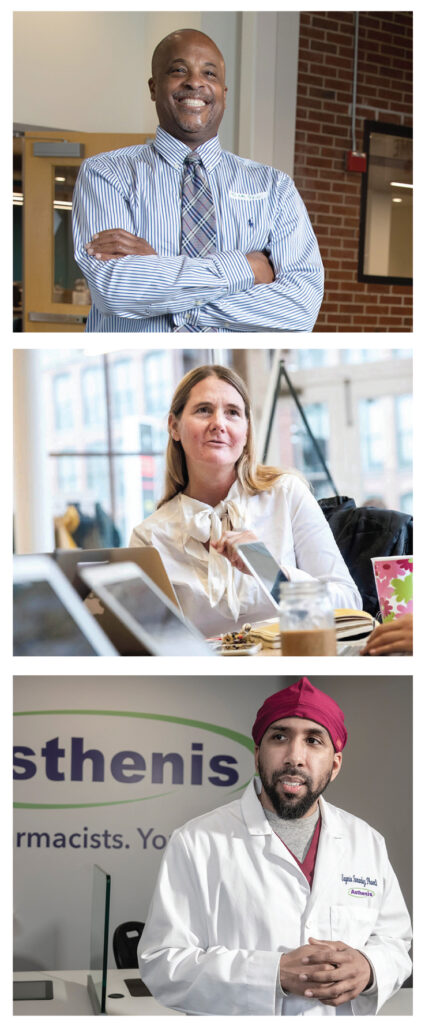

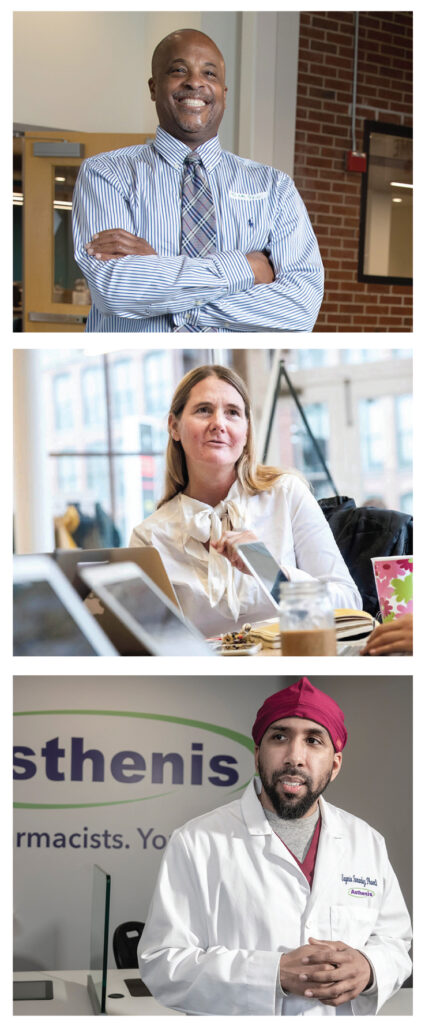

[caption id="attachment_337020" align="alignright" width="376"]

LEADERS: Pictured from top: C.C.

Business Corp. President Marcellus Sharpe; Social Enterprise Greenhouse CEO Kelly Ramirez; and Eugenio Ferndandez Jr., owner of Asthenis Pharmacy in Providence. / PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY; PBN FILE PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO; PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

VALUE ADDED

While many state and private programs, such as Goldman Sachs’ 10,000 Small Businesses and those through Rhode Island Commerce, include people of color, they don’t set specific targets or give their applications extra weight because of their minority status. That’s a problem, said Jessica Vega, program director for SEG’s Central Falls and Pawtucket office.

“Sometimes we like to pretend race isn’t there, but if we continue to do that, we’re perpetuating the problem,” she said.

Providence Mayor Jorge O. Elorza agreed.

“There’s a lot of value in having something designed specifically for minority-owned businesses,” said Elorza, whose parents immigrated to the U.S. from Guatemala. “There’s a certain cultural competence and comfort that people feel participating in them.”

In addition to its own minority- and women-owned enterprises ordinance, with a goal of 20% participation in capital improvement projects, the city has tried to ease entry for businesses owned by people of color – digitizing and streamlining licenses in multiple languages, for example. The city also in 2018 launched the PVD Self-Employment program, which targets entry-level entrepreneurs who may have been laid off or experienced difficulty finding other jobs. Nearly 70% of the 148 graduates to date are people of color.

Those early stages of starting a business are particularly challenging for people of color. A 2016 report from the University of California, Santa Cruz, found that Black and Latino business owners began their ventures with far less working capital than their white peers, which in conjunction with lower credit scores makes it harder for them to secure bank loans or if they do, often comes with a higher interest rate.

Additionally, most capital available for minority-owned businesses is based on debt, such as loans, versus equity capital such as angel investment and venture capital, Katz’s report noted.

John Florez, founder, CEO and president of Drupal Connect, spoke about his struggles finding capital when he started his web-development firm in Newport in 2009. A former Wall Street stockbroker, he had financial savvy but few local family connections to help pull together funding – Florez is originally from Colombia.

Two years ago, Florez moved his company headquarters to Austin, Texas, where he said there were better opportunities to work with large companies. He still maintains a small office in Newport, but a majority of his 35 employees are in Texas.

Since relocating the company, Florez has been struck by the marked difference in outreach and programming available to minority-owned businesses. While Rhode Island offered little in the way of minority-specific business support, especially in the early days of his company, he has found an ample array of opportunities in Texas, he said.

Florez described unsolicited, in-person outreach from Hispanic business-development programs in Austin as an example of the welcoming climate for minority-owned businesses there. He attributed the difference between Texas and Rhode Island in part to the larger minority community in Texas and the number of years programs for minority businesses have existed there.

‘LET’S WORK TOGETHER’

Helping people of color start and grow their own business brings a multitude of benefits to the larger economy.

For one thing, research indicates minority business owners are more likely than white business owners to hire people of color.

“The more Black businesses you have, the more employment you can generate within that community,” said Cynthia Scott, vice president of the Rhode Island Black Business Association.

Brewer, for example, estimates that 70% of the company’s 39 employees are minorities, while Florez said 20% of his workers are people of color.

Minority-owned businesses can also enhance the cultural diversity and array of services available. Fernandez, a native Spanish speaker, said his ability to converse with patients in their native language also helped bridge an important gap in communication about prescriptions and general health. That he grew up on nearby Hanover Street also helps him relate to patients.

“If you want to be a good health care practitioner, you have to take into account someone’s cultural beliefs, where they come from,” he said.

[caption id="attachment_337019" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

UPHILL BATTLE: Nissi Naturals co-owners Andrew and Anna Mangeni make soap. Anna Mangeni says starting and growing the hair and skin care products store has been challenging because it’s difficult to access capital as a minority-owned business. PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY[/caption]

Nissi Naturals also promotes cultural diversity, drawing upon co-owner Andrew Mangeni’s Ugandan roots in its use of certain ingredients such as shea butter.

The temporary closure of the Pawtucket store made the couple reconsider the business model, shifting away from retail and trade shows to a focus on manufacturing and online orders. Andrew Mangeni’s unemployment benefits, combined with the income Anna Mangeni earns in a separate, part-time job, have sustained them for now, although they are unsure how long that would last.

But the pandemic has brought the couple closer to others in the business community, their shared struggles a source of comfort amid uncertainty.

“Competition has been replaced by the idea of ‘let’s work together,’ ” Anna Mangeni said.

And Floyd’s death may be the start to the racial reckoning business owners such as the Mangenis have been waiting for.

“People are really waking up to how we are treated differently,” Anna Mangeni said.

Brewer was more skeptical.

“Not in my lifetime,” he said of systemic racial change, adding that “places that have more minorities in high positions in government maybe will get it faster, but in Rhode Island we’re not fortunate enough to have that.”

Nancy Lavin is a PBN staff writer. Contact her at Lavin@PBN.com.