NEW YORK – Amazon.com Inc. says it wants to remake health care for its workers. But its biggest rival is beating it to the punch.

Walmart Inc., the largest private employer in the United States, has been buying health care for its workers directly from providers in six different regions – bypassing insurers who usually negotiate with doctors and hospitals. The retailer is trying to find out if its formidable purchasing power can squeeze out middlemen and drive down costs in the same way that its tough bargaining has brought down prices for shoppers.

“We wanted to see what was more effective – what works, and what doesn’t work,” said Lisa Woods, the company’s senior director of U.S. health care. “If we can’t impact and influence cost or how cost trends are increasing, then we need to change or do something different.”

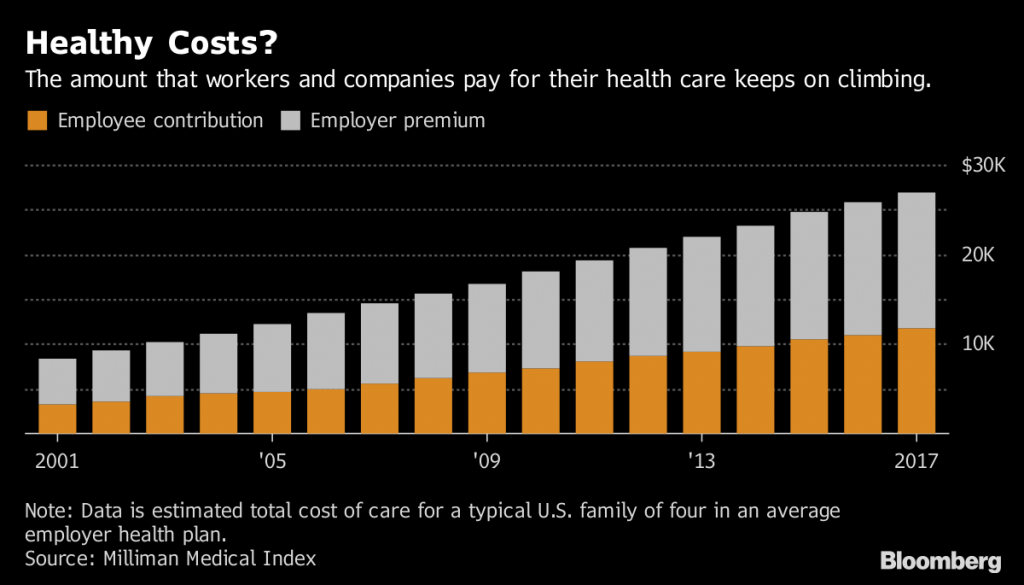

Companies are the largest providers of health insurance in the U.S., giving more than 150 million people access to coverage. While premiums have soared 55 percent over the past decade, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, most firms have done little tinkering with their health plans beyond asking employees to pay higher contributions and out-of-pocket costs.

But the outcry over rising costs is growing. President Donald Trump has decried high drug prices, while his administration has taken aim at middlemen they have faulted for a lack of transparency. Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb this week called out drug plans over a “rigged payment scheme.”

Industry makeover

That pushback is contributing to a rapid-fire refashioning of the health care business. A wave of previously unconventional deals has joined together insurers and pharmacy-benefit managers, culminating in Thursday’s announcement that Cigna Corp. agreed to acquire drug-plan giant Express Scripts Holding Co.

Increasing the pressure on health care companies: Employers aren’t sitting around waiting for the industry to get costs under control.

Amazon in January said that it, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Berkshire Hathaway Inc. would set up a new business to improve their employees’ health care. Berkshire Chairman Warren Buffett called high health costs a “tapeworm” afflicting the U.S. economy.

Others companies are beginning to experiment more quietly, too. Like Walmart, employers from private-equity giant Blackstone Group LP to postage-meter maker Pitney Bowes Inc. are trying new ways of getting better care at lower cost.

Walmart has been testing its new plans, known as accountable-care organizations, or ACOs, for two years. ACOs, which can be set up by employers on their own or with an insurer’s help, limit consumers to a smaller group of care providers.

ACOs also include financial incentives for doctors and hospitals. For example, health providers may receive extra money for making sure workers get treatment for chronic conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, or cancer screenings.

Employers often balk at making big changes for fear of upsetting workers, especially in a tight labor market, said Suzanne Delbanco, executive director of Catalyst for Payment Reform, a group of companies including Walmart that are pushing insurers and providers to do a better job of caring for workers. But high health costs are squeezing workers and firms alike.

“Employers are aware that Americans are increasingly willing to make tradeoffs between choice and affordability,” she said. “It’s a different era.”

Walmart says its ACOs have seen lower hospital admissions and emergency-room visits, while trips to primary-care doctors have risen. It’s too early to say whether Walmart is saving money, said Woods, the health executive, though premiums tend to be lower for workers who choose the plans.

Catching on

ACOs are catching on with other companies. About 21 percent of large employers are using them, though most are using ACOs set up by insurers, according to a National Business Group on Health survey.

The

The

Medicare health program for the elderly also embraced ACOs, pushed by provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The organizations take several forms, and the results have been mixed. Some have shown cost savings, while others haven’t, and some systems have dropped out as well.

Finding ways to generate more savings or limit future cost increases is difficult, according to Robert Galvin, chief executive of Blackstone’s Equity Healthcare, which handles health benefits for 51 companies including the private-equity giant itself and firms it owns.

Equity Healthcare has kept per-member cost increases below those of other corporations every year since it was started in 2009, according to its website. Typically, Equity initially controls expenses by shifting workers to health plans with higher deductibles while nudging them to get care for chronic ailments and take their medications. It began using ACOs set up by UnitedHealth Group Inc. and Aetna Inc. in 2017.

“What we’ve been doing for a long time has clearly hit a wall,” he said. “When you look at how much people are paying versus their take home pay, we have gotten to a time when it’s getting to be unaffordable for normal people. So we have to do something different.”

Galvin is skeptical of the savings potential from ACOs, pointing to the disappointing results from Medicare’s experiments.

“Some will be able to deliver better care, and I think many won’t, and I think the question is, what are the key things that differentiate them,” Galvin said.

UnitedHealth, Aetna and Cigna Corp. say their accountable-care arrangements offer lower costs and improved quality, though they provide limited data to support that.

Aetna said costs for individuals in its ACOs are $29.25 lower per person each month, compared to the company’s broader-network plans, though it says that savings may be smaller when compared to more limited networks.

Cigna said its ACO-like plans saved $424 million in aggregate from 2008 through 2016, though just more than half of the arrangements generated savings.

UnitedHealth’s report touts lower costs and higher quality without giving a specific savings figure. The company says it provides detailed quarterly data to clients.

Need for change

RH, formerly Restoration Hardware, had struggled to get good data from its insurers. The company switched this year to a startup, Collective Health, that promises to provide more data on how RH can make its benefits more efficient, improving care for its workers while limiting cost increase. RH expects to reduce its medical costs by about 3 percent to 5 percent this year.

“Health care is so bad and employers are spending so much money, it is something that just has to change,” said Karen Boone, the company’s chief financial and administrative officer.

Zachary Tracer is a Bloomberg News staff writer.