Meghan M. Hill wanted to be a teacher since she was in the fourth grade.

Of her chosen career path, the 23-year-old Scituate native said: “No two days are the same. … Building relationships with the students is rewarding, [especially] seeing how they grow and knowing you’re part of that.”

(Editor’s note: This is the first in an occasional series of stories on issues affecting the education of teachers in the region.)

But the 2018 Rhode Island College graduate is joining a profession in which demand may soon outstrip supply, if the current national trend of declining education graduates continues.

“From my core group of friends, I was the only one to go into education,” she said of high school classmates.

Hill holds a Rhode Island certificate for elementary education, grades one through six, with an endorsement in middle school math. In January, she started a six-month position as a long-term substitute teacher at RIC’s on-campus Henry Barnard Elementary School.

At RIC, she knew at least 11 fellow education majors who dropped out over time. The reasons, she believes, include the heavy workload and an emphasis on “standardized testing [that] scared people away.”

Calling it a “traditional” career choice, she added pay was likely a deciding factor for some too.

“[Teachers are] not going to be paid as much as people in other fields,” Hill said.

Rhode Island schools and others in the region have felt the sting of declining interest in teaching careers. Two-thirds of the 12 local teacher-education programs have seen a decrease or stagnation in education-major graduates between 2008 and 2018, including RIC and Providence College, the two largest.

Four local schools – Roger Williams University, Brown University, the Community College of Rhode Island and University of Massachusetts Dartmouth – have increased education graduates over the decade, though their programs remain relatively small with 64 or fewer 2018 graduates. Most credit their success to redesigning how the program functions, an expanded curriculum connected with industry needs, top-notch marketing and low teacher-to-student ratios.

The rest are all taking steps to reverse the negative trend, with some schools focusing on curriculum redesign while others concentrate on recruitment from previously underrepresented socio-economic groups, among other initiatives.

The challenge for them is compounded by simultaneously decreasing or stagnant education department faculty. As the number of education students declined at most schools, nine education departments either decreased full-time faculty or were stagnant, while the part-time count at six schools either fell or stayed the same, making it difficult to ramp up quickly if student demand suddenly increased.

And this is all happening at a time when demand for teachers, both locally and nationally, is expected to increase.

In 2009, the National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future found more than half of U.S. teachers were baby boomers expecting to retire before 2019. During the 2008-09 academic year, slightly more than 50 percent of Rhode Island’s teachers were aged 50 or older, according to the report. That demographic accounted for 53.3 percent of Massachusetts teachers the same year.

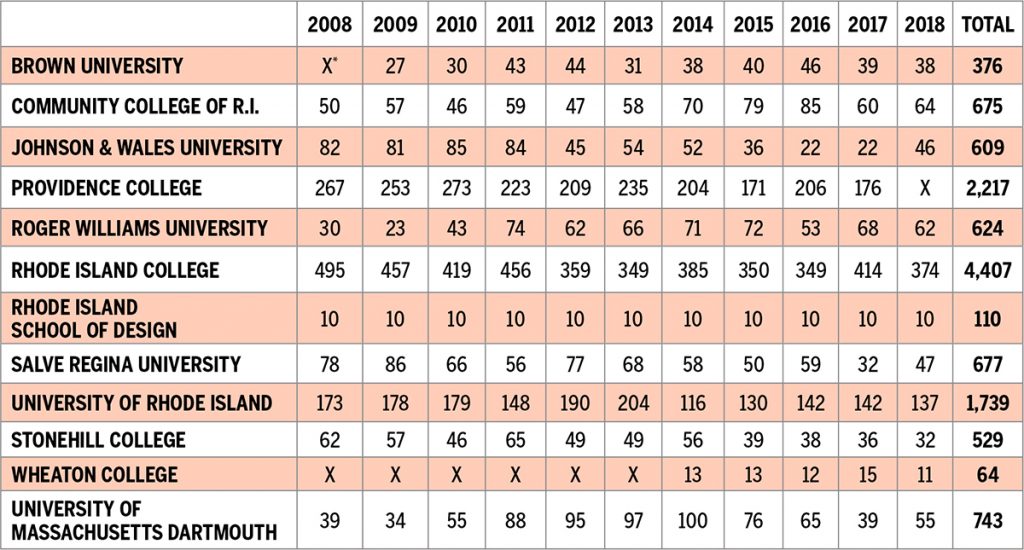

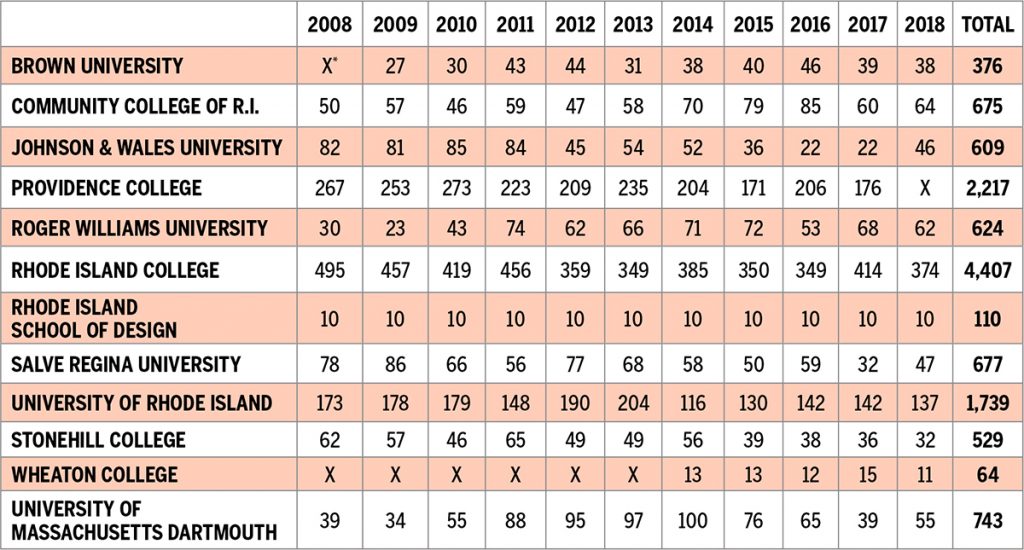

[caption id="attachment_247932" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

EDUCATION GRADUATES: TEACHER SHORTAGE? Most local schools have seen the number of graduates earning degrees in education shrink over the past decade. Four that have bucked the trend in recent years – Brown University (which did not provide data for 2008), Community College of Rhode Island, Roger Williams University and UMass Dartmouth – operate relatively small education programs with 2018 totals that were still below their highs for the decade.*Data not provided by schools for full- or part-time faculty marked with X in table. / PBN RESEARCH[/caption]

DWINDLING DIPLOMAS

While some local schools could not provide a complete count of education graduates per year between 2008 and 2018, the data provided to Providence Business News generally shows the business of teacher training is contracting at local schools.

The 10 schools that provided data for 2008 graduated 1,286 students that year. In 2018, 11 schools provided data, one more than for 2008 but the total number of graduates still declined 31.9 percent to 876.

Comparing data from 2008 and 2018, the schools that gained the most graduates last year were RWU (32), UMass Dartmouth (16) and CCRI (14).

Conversely, the schools with the largest decreases last year were RIC (121), Providence College (91 in 2017), Johnson & Wales University and the University of Rhode Island (both with 36).

A similar trend has occurred with education department faculty.

The nine schools that provided data for 2008, the height of the Great Recession, employed 143 full-time education faculty.

Ten schools provided data for 2018. Those schools employed 86 full-time education faculty last year, a 39.9 percent decline despite the inclusion of an additional school.

Part-time education department employment similarly fell, by 47 percent, from 168 at eight schools that provided data for 2008, to 92 employed by eight schools last year.

URI lost the most full-time faculty (five), followed by JWU (three) and Brown (two). The greatest part-time faculty losses were at RIC (15) and PC (four).

Wheaton College was the only school that managed to grow its full-time education department faculty last year compared with 2008, increasing by one staff member to a total of five.

Only four schools reported more part-time education faculty compared with 2008. URI employed eight more in 2018. Salve Regina University and RWU added three each compared with a decade earlier. UMass Dartmouth added seven in 2017 but did not provide data for last year.

It’s a similar story nationally. For almost a decade, the nation’s education programs have graduated fewer and fewer prospective teachers.

The number of education bachelor’s degrees conferred in the United States fell from 102,582 in 2007-08 by nearly 11,000, or 10.7 percent, to 91,623 in academic year 2014-15, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

NCES data paints a similar portrait regarding the number of master’s degrees conferred nationwide. The metric stood at 175,880 in academic year 2007-08 and fell more than 29,000, or 16.7 percent, to 146,561 in 2014-15.

If the number of education faculty continues to falter, it will be more difficult to find qualified teachers to replace those retiring.

“If you don’t have critical masses of students,” said David Byrd, director of the URI School of Education, “that can impact [a school’s] ability to put forward hiring requests … [and] the ability to offer robust programs” addressing shortages in certain specialty areas.

Locally, one measure of the teacher shortage in Rhode Island is emergency certificate applications. Awarded by the state, these certificates are given to prospective educators at a local district’s request when a fully certified educator cannot be secured. The latest data shows the volume of applications is on the rise, jumping from 249 in 2014-15 to 341 in 2017-18.

While “emergency certificates are the best source of information” the state can provide, said Lisa Foehr, R.I. Department of Education chief of teaching and learning, she cannot explain the increase in applications other than to say it is indicative of districts not being able to hire fully certified teachers. State education officials said that because statistics on local teacher counts are kept by individual school districts, they could not provide additional data measuring local demand.

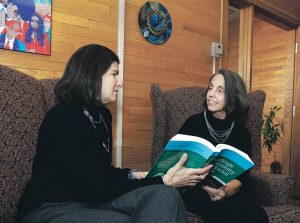

[caption id="attachment_247933" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

DOWNWARD TREND: Julie Horwitz, left, and Gerri August have served as co-deans of Rhode Island College’s Feinstein School of Education and Human Development for roughly 18 months. Horwitz said the attractiveness of the teaching profession has been “compromised by some of the pressures put on teachers.” August sees the decline in education graduates in Rhode Island as a “microcosm of what’s happening nationally in the industry.” / COURTESY RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE[/caption]

WHAT HAPPENED?

Most local schools see the decline in education graduates as merely a reflection of the national trend.

“The attractiveness of the profession has been compromised by some of the pressures put on teachers,” said Julie Horwitz, interim co-dean for RIC’s Feinstein School of Education and Human Development, listing advanced placement tests and teacher evaluation.

“Rhode Island is a microcosm” of what’s happening nationally in the industry, said Gerri August, the other interim co-dean of the education school, the state’s largest teacher-training school.

August feels teaching cannot compete with the draw of working directly in a student’s area of expertise.

“[Other] industries pay so much more and it’s hard to recruit … [when those opportunities] are so lucrative,” she said.

Faculty retention, explained August, is “driven by the needs of Rhode Island [schools] and enrollment.”

While RIC’s education graduate count dropped by more than 100 over the decade, the education faculty count has stayed roughly the same. Compared with 2008, only one full-time faculty member was added, while 15 part-timers were dropped as of 2017. RIC faculty data for 2018 was not available.

“We don’t have the option of culling our faculty to respond to market needs … without any kind of egregious violation,” said August, citing the tenure system at RIC. So part-time faculty were curbed instead.

In his 15th year heading URI’s School of Education, Byrd attributed the declining number of education graduates to a “negative perception” of a teaching career but added the entrance requirements for URI’s program may also be too high to catch most of those interested. Students must be in the 60th percentile of SAT scores to enter any Rhode Island-based program, according to Byrd.

“That’s a pretty high bar,” he said.

In fact, the bar has steadily climbed. According to Byrd, the cutoff was the 50th percentile in 2016-17, rising to the 60th for the current academic year and was previously expected to jump to the 66th percentile for 2020-21.

However, on Friday, the R.I. Department of Education told PBN they had decided to put on hold the previously-schedule increase of the SAT admission benchmark from 60 to 66. They did not say how long the increase would be put off.

The face of the URI education department also has changed.

While five full-time positions have been eliminated in the past decade, eight part-time positions have been added.

‘I wish the environment was more supportive of people coming into teaching.’

DAVID BYRD, URI School of Education director

Byrd is unsure if URI’s reputation as a top teacher trainer has suffered.

“I wish the environment was more supportive of people coming into teaching,” he said.

Jennifer E. Swanberg, Providence College’s dean of the School of Professional Studies, feels low pay contributes to the negative perception many students have of teaching as a lifelong career.

At PC, she adds, the education program also places a lot of demands on students’ time.

PC undergraduates, in particular, enroll in a dual certificate program in which they study both elementary and special education or secondary education, with a concentration in a specific subject.

“Their time commitment … might be much more than a typical undergraduate not pursuing education,” she explained.

BUCKING THE TREND

Yet some local schools have managed to grow their programs after dips.

RWU and UMass Dartmouth have increased the number of education graduates compared to 2008, though both had higher graduation totals in the past decade.

‘We keep close watch, students know they won’t fall through the cracks.’

RACHEL MCCORMACK, RWU education department faculty chair

Starting with 30 graduates in 2008, RWU in 2018 graduated 62, after reaching a high of 74 in 2011. The success of the program, said Rachel McCormack, RWU education department faculty chair, comes down to intimacy and attention to the market.

There are nine full-time faculty educating roughly 200 students, she explained – “Students get a lot of personal attention.” RWU education courses range in size from 15 to 25 students. Each faculty member advises roughly 20 to 25 students a year.

“We keep close watch. Students know they won’t fall through the cracks,” said McCormack.

Paying attention to the market, analyzing the local and national education systems to determine which new education ideas to follow, keeps the faculty up to date, said McCormack.

For example, she said, department faculty are currently writing a proposal for a STEAM core concentration and minor that would allow education students to specialize in science, technology, engineering, arts and math, in addition to their education major.

Given Rhode Island’s size, and the fact that most RWU education graduates seek employment elsewhere, McCormack said the department is debuting a course that allows students to study for a Massachusetts certification.

Unlike some of her colleagues, who cite a negative perception of the industry, McCormack said: “For a lot of students coming into RWU, they’re seeing education as a career they can hold onto and in which they can thrive.”

From 10 in 2008 to nine in 2018, RWU full-time education faculty has held steady, while part-time educators rose from 16 to 19, after hitting a high of 21 in 2010.

“We’ve tightened our schedule so we’re not teaching a class with 11 students. We’re teaching classes with 25. … [We] prefer teaching classes with a sense of community” and 25 is better for that, she said.

UMass Dartmouth saw its program grow steadily in the first half of the past decade, reaching a high of 100 education graduates in 2014. But the number of education degrees conferred steadily declined in subsequent years to a low of 39 in 2017, before jumping up by more than 40 percent last year, to 55.

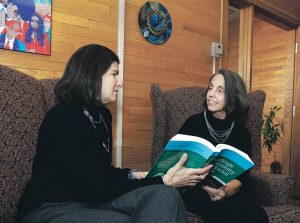

[caption id="attachment_247934" align="alignright" width="300"]

TEACHER TEAM: Julie Horwitz, left, and Gerri August have served as co-deans of Rhode Island College’s Feinstein School of Education and Human Development for roughly 18 months. In that time, RIC administrators have sought to recruit students from previously underrepresented socio-economic groups, so the state’s teachers reflect the regions in which they teach and the student demographics which they instruct. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

Receipt of $1 million in federal grants, and a “streamlining” of the program resulted in UMass Dartmouth reaching triple digits in 2014, explained Coordinator of Graduate and Admissions Licensure Traci Almeida. With an eye to “reducing time and cost,” the post-baccalaureate and master’s degree components were merged.

The steady decline between 2015 and 2017, said Almeida, reflected a nationwide enrollment slump in teacher preparation. A second redesign of the program, in 2018, helped counter the decrease. Knowing many UMass Dartmouth-trained teachers are hired by Fall River and New Bedford districts, the school pivoted its focus to those who had reacted to the shortage and, without prior teacher training, sought open education positions locally. Today, between 50 percent and 60 percent of UMass Dartmouth education students are currently working in classrooms, said Almeida.

“General pre-service preparation [of students] wasn’t cutting it,” she said. “We had to change [our program] and we’ve seen an uptick ever since.”

‘COMING BACK’

According to Learning Policy Institute 2018 data, the state has a way to go to attract top teaching candidates.

Smack in the middle of the 1-5 range, Rhode Island has a teacher-attractiveness rating of 3.03 – a gain of 0.3 percentage points from 2016, but still the lowest in New England. Wyoming had the highest rating in the nation, at 4.57.

The decline in education graduates and contraction of some education departments in the region provide an opportunity for self-analysis, said Dan Egan, president of the Association for Independent Colleges and Universities of Rhode Island.

He feels teaching will become more popular if it becomes more lucrative.

“Post-recession, we see a trend in decisions made [regarding] course of learning tied to higher income,” said Egan.

He suggested schools emphasize “greater residency and hands-on [time] aligned with traditional coursework” as a way to “attract new candidates.”

RIC is already “in the midst of a comprehensive redesign,” according to August.

For the past 18 months, since she and Horwitz were appointed, RIC administrators have sought to recruit students from previously underrepresented socio-economic groups. Their goal is for the state’s teachers to reflect the regions in which they teach and the student demographics that they instruct.

In addition, August noted certain programmatic requirements “have been very difficult to complete in four years.”

She and the department are looking to trim the math and sciences and special-education programs in particular, until they are “much more reasonable in terms of the number of credits required, without compromising the content knowledge.”

URI’s Byrd believes the state’s flagship research institute is already on the rebound.

“We’re coming back,” said Byrd, recounting URI’s education graduate count hit a low of 116 in the 2013-14 academic year and is on the upswing.

One reason, he said, is because focus on student experience has increased. For example, URI special-education students must file as dual majors and complete two semesters of student teaching, extending their on-campus tenure by a semester. He hopes to streamline this process.

Byrd also feels the education program has “stabilized” thanks to enrollment perks, including additional certificates, direct admission and a program to prepare students for standardized testing.

‘PC can’t change the hiring cycle, but the state can [help].’

BRIAN M. MCCADDEN, PC dean of graduate programs

Local schools are also doing what they can to reverse the declining interest in education careers.

However, administrators warn this won’t be easy.

“There has been some improvement over a few years and the data shows that,” said Byrd. However, he added, “It will be a long-term problem supporting education in Rhode Island.”

Noting the national decline in students graduating with education degrees, Swanberg called on state government to lend a hand.

“To offset these trends, there is a need for federal and state policymakers to develop innovative policies to promote the recruitment, retention and development of quality teachers,” she said.

State-level loan forgiveness, prioritization of professional-development opportunities for local teachers, investment in “quality work environments” for teachers and “strengthening licensure reciprocity to ease the burdens of cross-state mobility” are all ways Rhode Island’s government can increase teacher retention, according to Swanberg.

Brian M. McCadden, PC’s dean of graduate programs, said the state should be more involved because, “It’s a good idea to have the different stakeholders in the process.”

Schools “can address [the teacher shortage] in some ways, but not all,” he said. For example, many open teacher positions in Rhode Island are not posted until June, whereas graduating seniors are looking for jobs months earlier, before their leases run out and they return to out-of-state homes, he said.

“We produce teachers,” said McCadden. “PC can’t change the hiring cycle, but the state can [help].”

Emily Gowdey-Backus is a staff writer for PBN. You can follow her on Twitter @FlashGowdey or contact her via email, Gowdey-backus@PBN.com.