PROVIDENCE – One year after former Gov. Gina M. Raimondo declared a state of disaster emergency over the COVID-19 pandemic, some have grown weary of the seemingly everlasting crisis and are pushing to lift the declaration and ease restrictions. The state emergency declaration, which has been renewed on a monthly basis since its March 9 start date, is currently set to expire on March 17.

Gov. Daniel J. McKee has not said publicly whether he will renew the declaration again, though in a March 4 press conference the state announced it would loosen rules around events and capacity at restaurants and gyms. Andrea Palagi, a spokeswoman for McKee, said in an emailed response to inquiries for comment, “while Rhode Island’s health numbers continue to trend in the right direction and we continue to ease restrictions on businesses – the state and country continue to remain in a public health crisis due to COVID-19.”

But some municipal leaders, many of whom followed Raimondo with their own emergency orders last March, are questioning whether the continued emergency state is necessary. Others have already done away with theirs.

Exactly how many cities and towns still have emergency declarations on the books is unclear. The Rhode Island League of Cities and Towns is not tracking that information, according to Executive Director Brian Daniels.

The city of Warwick does not. Mayor Frank J. Picozzi said the city emergency declaration ended in the summer, before he took office.

The city is still enforcing state restrictions on business capacities, social distancing and mask-wearing. But Picozzi saw little benefit to maintaining an emergency declaration, particularly as residents become increasingly tired of the rules.

“There’s a certain level of exhaustion for people if you’re in code red all the time,” agreed Narragansett Town Manager and Commissioner of Public Safety James R. Tierney. Narragansett in May also lifted its emergency declaration, simply because renewing the declaration and an ever-changing set of executive orders became too burdensome, he said.

Narragansett Town Council President Matthew Mannix last May introduced a resolution that would have exempted town police from enforcing state executive orders, but the proposal was withdrawn due to lack of support from fellow council members. Mannix did not respond to multiple emails for comment but Tierney was unaware of further discussions to defy state restrictions.

In North Providence, where an emergency declaration is still in place, the Town Council has started to push back on restrictions. The council on Feb. 25 approved a resolution urging the governor and state legislators to allow restaurants with bar licenses to resume normal bar hours, describing the 11 p.m. curfew as “arbitrary” and “without accompanying scientific or rational explanation.”

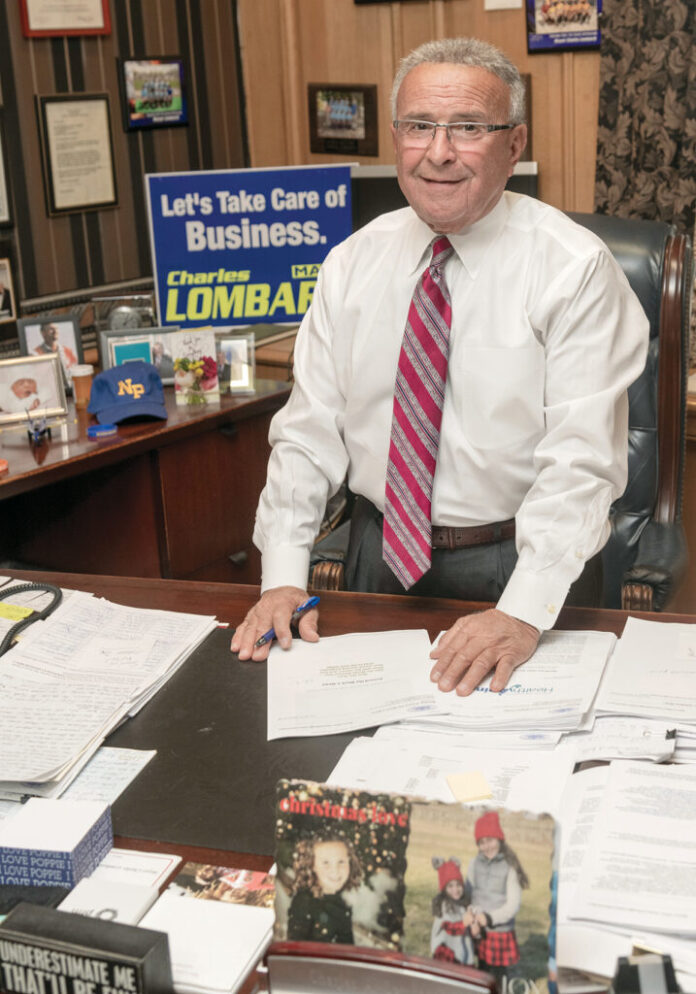

North Providence Mayor Charles A. Lombardi, who also serves as president for the R.I. League of Cities and Towns, said he anticipated lifting the city’s emergency order “very very soon.”

“Numbers are down and it seems like we’re heading in the right direction,” Lombardi said.

But decreasing case counts is not the only motivator.

Lombardi and other municipal leaders said they felt pressure from the business community to reopen, noting repeated noncompliance that suggests the emergency orders and restrictions are not being followed anyway.

“Some businesses have just about had it,” Lombardi said.

Striking the balance between supporting the hard-hit business community and following public health guidelines is difficult, Providence Mayor Jorge O. Elorza agreed. Providence was one of the first municipalities to declare an emergency, on March 12, and has renewed it ever since.

While Elorza, too, acknowledged that “COVID fatigue” is a real problem, the initial emergency declaration was actually supported by many businesses, particularly those in the hospitality industry who needed that declaration in place to get out of contracts or get reimbursed for losses by insurance companies, Elorza said.

After breaking from state guidelines in the early months of the pandemic – enacting stricter rules around park access, street closures and other topics – the city has largely tried to align its efforts with the state, Elorza said. He anticipated keeping an emergency declaration as long as the state. However, he also admitted that the higher case counts and lower vaccination rates in Providence compared to other municipalities may merit a more cautious approach.

“The worst thing we can do for the economy is open up too soon, have cases explode, and then have to pull back again,” Elorza said.

It’s important to distinguish the purpose of a state or municipal emergency declaration, said Kenneth K. Wong, a professor and director of the urban education policy program at Brown University. In addition to making the state or a city eligible for federal aid, the declaration grants an executive – the governor, or a mayor or town manager – power to act quickly in responding to a crisis: allocating personnel or funds and issuing executive orders without legislative approval.

In that sense, the declaration has not lost effectiveness over time; the same power still applies. But the societal and cultural perception of the crisis, and compliance with the rules enacted under a state of emergency, may wane, particularly during a year-long declaration the likes of which has never happened before, Wong said.

And as more residents get vaccinated, there’s little need for that kind of unilateral authority, according to R.I. House Minority Leader Blake A. Filippi, R-New Shoreham. Filippi, who has criticized the state for overly harsh restrictions, said the governor “must” end the state of emergency as soon as all people over 65 who want to get the vaccine are immunized.

He also faulted the R.I. General Assembly for “failure” to better oversee executive decisions during the year-long emergency state. Fellow Republican Representative George A. Nardone has introduced legislation to address this by creating a a joint legislative committee to oversee disaster declarations and requiring legislative approval for emergency declarations lasting more than 90 days.

“Without robust oversight, I can’t in good conscience say [a state of emergency] should continue,” Filippi said.

Only two states, Michigan and Alaska, have lifted their state emergency declarations, according to the National Governors Association. However, more than a dozen states, including neighboring Connecticut and Massachusetts, have announced plans to ease some or all restrictions, putting additional pressure on Rhode Island in Filippi’s eyes.

“We are a regional economy whether we like it or not,” he said.

Nancy Lavin is a PBN staff writer. Staff writer Cassius Shuman contributed to this story.