Looking to expand her social circle, and to become more involved on campus, Allie E. Lewis two years ago decided to join The Good 5 Cent Cigar, a student-run newspaper at the University of Rhode Island.

Lewis, a Cranston native, studied biology at the time. But she quickly fell in love with writing stories, developing sources and meeting deadlines. Shortly thereafter, she switched her major to journalism and now wants to be a foreign correspondent or political reporter for a newspaper after graduating next year.

Her career choice has her family worried.

“My family is very concerned that I won’t be able to get a job,” she said.

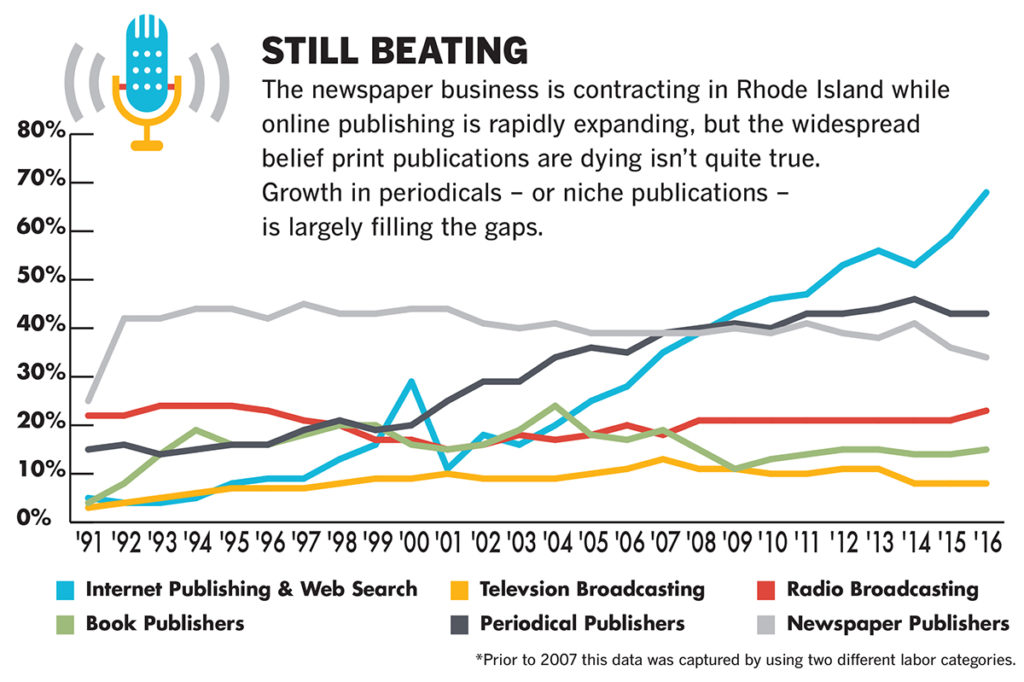

The concern is reasonable. Overarching trends for newspaper employment are gloomy. Since 1991, the number of newspaper jobs in Rhode Island fell 71.8 percent to 676. Since 2001, the state’s decline of 64.8 percent outpaces the national trend of 57.8 percent. Last year, the average newspaper salary in Rhode Island totaled $43,962, representing a 20.4 percent decline from its peak in 1997.

But if Lewis is really interested, she should find work here.

The widespread narrative that newspapers are dying isn’t quite accurate, as sharp declines are not necessarily indicative of death. And while many traditional and big-name newspapers suffer from entrenched and antiquated business models, some locally owned newspapers are adapting and in some cases growing.

“Everyone told me, ‘You’re dead,’ ” said Thomas V. Ward, owner of Breeze Publications Inc., which publishes several community newspapers in print and online, including its flagship paper, The Valley Breeze. “Last year, we had record revenue. Don’t tell me we’re dead after we have record revenue.”

There’s little evidence to suggest the newspaper model – especially at the local level – will ever return to its previous glory. Many outlets throughout Rhode Island do, however, offer proof that people and businesses – at least for now – are still willing to pay for and advertise in local newspapers.

But will they continue to do so if the publications are no longer locally owned?

Countless local newspapers have been shuttered across the country in recent years.

The number of family-owned newspapers has declined, a trend that continues today. Only 15 percent of America’s daily newspaper circulation is under independent control, a far cry from 59 percent in 1975 and 90 percent in 1900, according to a recent report in the Wall Street Journal.

Five of the six newspaper sales nationally in the first quarter of 2017 involved a larger media group buying out a family-owned paper, according to the report.

Rhode Island isn’t immune. The state’s newspaper of record, The Providence Journal, has been owned by an outside group since the 1990s. A handful of suburban newspapers, including the Woonsocket Call, the Kent County Daily Times and the Pawtucket Times, were purchased by an Illinois-based company in 2007.

In both cases, operations and staffing have seen deep cuts.

“There’s a danger with [nonlocal ownership] because if big companies grab up local newspapers, they become part of a formula and are no longer connected to the local community,” said John Howell, owner of Beacon Communications, which owns the Warwick Beacon, the Cranston Herald and the Johnston Sun Rise.

“It’d be a shame if it happened here,” he added.

There is a sense among some in the industry, however, that local newspapers can hold on to their independence simply because many enjoy near-blind reader loyalty. The dynamic is at least partly due to the parochial nature of a state where many call the 30-mile drive from Providence to Narragansett a “road trip.”

“For our core newspapers, about 82 percent of homes tell our auditor they pick up the paper,” Ward said.

INDUSTRY IN FLUX

The R.I. Department of Labor and Training counts 34 newspaper publishers in Rhode Island, marking five fewer newspapers than the state’s number of cities and towns.

The total includes daily and weekly newspapers scattered throughout the state. It’s five fewer than a decade ago, and 10 fewer than 15 years ago. But where traditional newspapers are declining, other publications are growing.

Periodical publishers, including magazines and trade journals, have nearly doubled to 43 since 2001, bucking the trend nationally, which is in decline. At the same time, internet publishers – a category somewhat skewed to include a variety of nonnews organizations – has grown from 11 outlets to 68.

“The whole industry is in flux,” said John Pantalone, chair of the journalism department at URI. “Nobody seems to have come up with a fool-proof model. Everybody’s got a theory. A model, I’m not so sure.”

The digital age has hurt newspapers, especially subscription-based outlets. Content was suddenly made available for free online, and newspapers were slow to charge for it. Publishers are still torn by the prospect.

“We do not have a pay wall on our website,” said Howell, who admits free publications have done better since the rise of the internet. “But we may go that way, because if you’re going to put more effort into the web stuff, people are going to expect it.”

Online readership has soared for most publishers contacted by Providence Business News. But with the lion’s share of revenue still tied to print subscriptions, sales, legal notices and – most importantly – advertising, the net result has largely been depressed top-line figures squeezed by the fact that digital ads cost much less than print ads.

Such uncertainty has pushed and pulled publishers in different directions.

“When the dawn of digital really started ramping up, every publisher was rushing to do everything. … It was like lemmings running off a cliff,” said John Palumbo, owner of Rhode Island Monthly Communications Inc., whose flagship publication is Rhode Island Monthly.

The digital age, however, hasn’t been all bad for newspapers. Online capabilities have expanded market reach. A Woonsocket resident no longer needs a physical copy of the Westerly Sun to know the scuttlebutt in South County. Snowbirds in Florida can visit Newportri.com to learn the latest on Aquidneck Island via The Newport Daily News.

Digital has also opened the door to new web- and mobile-based platforms, which pose new challenges – and opportunities – for local publications to reinforce the bonds with communities they serve and depend on.

“A lot of newspapers that will survive are going to be niche newspapers,” Pantalone said. “The smaller local newspapers are surviving, somehow, because they’re the only ones who are covering local news.”

FINDING A NICHE

Breeze publications – comprising five free weekly newspapers – averaged circulation of 61,458 in 2013, representing nearly a 20 percent increase from 2007, according to a 2013 audit, the most recent available, by Circulation Verification Council, a third-party community newspaper audit company.

Last year’s revenue exceeded $3 million, according to Ward.

“We do what nobody else does,” Ward said pointedly.

The Breeze publications, albeit successful by themselves, have also benefited from the shrinking of The Providence Journal. Known as the Projo, the state’s biggest newspaper started closing its once widespread community bureaus in the 1990s, a trend that accelerated through the 2000s.

Today the newspaper operates mostly out of a single building in downtown Providence. The Projo – like most daily newspapers – has sustained major drops in circulation, which fell from more than 200,000 in the 1990s to a daily average of 70,780, according to its media kit for advertisers.

But declining print readership of the state’s biggest newspaper has created opportunity for some community newspapers, especially with local advertisers.

“It has certainly been useful for us, because before – as a free newspaper – [advertisers] wouldn’t talk to you,” said Barry Fain, publisher of East Side Monthly and part owner of Providence Media Group Inc., which owns various news outlets, including Providence Monthly.

Providence Media Group – which Fain owns with Howell and Richard Fleischer – made a bid to buy the Projo from Dallas-based A.H. Belo Corp. in 2014. The deal would have brought the newspaper back under local ownership, but it never materialized. A.H. Belo eventually sold the paper to Gatehouse Media Inc., which is owned by New Media Investment Group Inc., a national media conglomerate.

Providence Newspaper Guild President John Hill says the number of Projo union employees fell from about 500 in the 1980s to roughly 100 today, including 20 reporters. Janet Hassen, the newspaper’s publisher, did not respond to a request for comment.

Local community newspapers, likewise, have absorbed their own declines and cut staff either through attrition, buyouts or layoffs. But being hyperlocal has protected them in some ways from the sting of steadily declining revenue suffered at larger outlets.

“I think our niche is being in that local space,” Howell said.

The Beacon, a subscription-based newspaper, has seen its circulation fall from about 11,000 to 7,000, he said. “I don’t think the core of the business in terms of providing community and local information has changed. There’s still demand for that. The mechanism for delivering it is changing, and the expectation that you get it sooner has changed,” he said.

A lot of other local niche publications, including Rhode Island Monthly, Providence Monthly, Providence Business News, and even some digital-only organizations, are finding some success diversifying business lines.

The approach, which includes hosting community events, awards ceremonies and other types of community gatherings, has helped relieve some of the downward pressure in print sales.

“With circulation, there’s no fast and easy way,” said Roger Bergenheim, owner and publisher of Providence Business News. “It’s a grind.”

PBN does about 7,000 print newspapers each week, earning the company about 52 percent of its total revenue. Another 35 percent comes from monthly events, and the remaining 13 percent comes from digital revenue, according to Bergenheim. PBN’s business-readership base has remained loyal, Bergenheim says, keeping circulation relatively stable. In the long term, he believes market forces will demand people pay for original content and new information, which bodes well for the news industry.

“You can’t run a business that’s losing money over an extended period of time. But people still want information,” he said. “I don’t care how we provide that information, whether it’s electronically, or in print, the market will make it right. Ultimately, those who do it right and don’t cut corners and provide something that’s needed will survive.”

At the moment, most signs point toward readers across the board moving to digital platforms for news consumption.

“I can’t remember the last time I bought a newspaper,” said Travis Escobar, president of Millennials Rhode Island, a young-professionals group based in Providence. “I’ve never really had a desire to pick up the physical copy.” Escobar, 26, reads a lot of news.

Part of his job each day requires him to scour for headlines and aggregate top stories both locally and nationally. He finds those headlines and stories on social media.

“Personally, I’ll go to Twitter,” Escobar said. “I follow a bunch of journalists locally and nationally, and my Twitter feed [has] become my news feed.”

DIGITAL EMERGENCE

The digital trend is reflected in research, as a 2016 Pew Research Center study shows most adults – 62 percent – get some news on social media, representing an increase from 49 percent in 2012.

Good news for newspapers is that 51 percent of people who read newspapers still do so in print form, according to another Pew study. But that number is down 4 percentage points from the previous year, and print revenue continues to decline.

For local newspapers, selling ads based on being local is also becoming more competitive. Social-media outlets, including Facebook, have developed geolocation capabilities, meaning it can track users’ locations and target ads accordingly, an attractive prospect to advertisers in search of a targeted audience.

“Facebook has made a big difference,” Ward said. “It’s coming after the advertisers.”

But Ward also points to evidence showing his print newspapers still have traction with younger readers, bucking the perception that millennials are only reading news online. A survey of his readership shows that 17 percent are aged 25-34, 24 percent are 35-44 and 25 percent are 45-54, according to an audit.

Digital-only news outlets, which don’t have traditional overhead costs of newspapers, are also challenged in the realm of advertising.

“We’re looking to grow our donor base because we see the writing on the wall with ads,” said Joanne Detz, co-founder of ecoRI News, an environmental news outlet. “There’s less and less space.”

Detz and her husband, Frank Carini, started ecoRI News in 2009. The duo is a good example of how digital-only can work. But it’s not easy, and the margins are tight. A lot of funding is tied up in grants and donations, which can come and go. The nonprofit outlet employs three full-time and five part-time employees.

But it is growing – both in readership and revenue. EcoRI News last year earned about 50 percent of its revenue through grants and advertising, 40 percent from donors and about 10 percent from events.

Bob Plain, publisher of RI Future, a progressive, online-only news outlet, splits his time working between the website and another job. RI Future employs two full-time contributors, but Plain estimates about 1,000 people write for the site throughout the year, ranging from state inmates to Gov. Gina M. Raimondo.

“Corporate-owned journalism [decries] the end of newspapers, but this is actually just journalism born again,” he said.

But there’s some evidence social media could become a partner, rather than a competitor, of traditional news organizations. In the wake of heavy criticism for its role in perpetuation of so-called “fake news,” or hoax content published online, Facebook recently announced a new initiative: “The Facebook Journalism Project.”

The social-media giant is looking to partner with news organizations to educate readers and support news outlets through its platform.

“There is more we must do to support the news industry to make sure this vital social function is sustainable – from growing local news, to developing formats best suited to mobile devices, to improving the range of business models news organizations rely on,” said Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook.

The announcement has yielded mixed reactions from the newspaper industry, which is caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to Facebook. The platform helps media outlets disseminate content, which boosts online readership numbers used to sell to advertisers. But they also compete with Facebook for advertising dollars.

In Rhode Island, though, who owns the news organization will likely continue to be a factor in reader loyalty – and long-term survival, says Pantalone.

“People prefer newspapers to be locally owned in Rhode Island,” he said. “Especially for the smaller newspapers in Warwick and Cranston, and the Valley Breeze and the papers in South County and Newport. It means something to them that there are local owners.”

In some ways, he added, it’s emblematic of Rhode Island.

“It’s part of Rhode Island’s culture that there are all of these small, locally owned papers,” he said. “People have begun to understand that absentee owners and reduced staffs is a problem because it’s much harder to find out what’s going on in the community where you live.”

VALUE OF PLACE

Finding new ways to further solidify that bond with local readers is the challenge many news organizations now face, according to Damien Radcliffe and Christopher Ali. The scholars are currently finishing a report about U.S. newspapers with circulation under 50,000 for Columbia University.

“To help them solidify their place in local communities, small-market newspapers are slowly beginning to commoditize one of their most unique selling points: the value of place,” the duo wrote for The Neiman Journalism Lab at Harvard University. “By bringing people together – both literally and figuratively – newspapers can help create and reflect a sense of community that larger publications may struggle to replicate.”

Howell, who started with community newspapers in the 1960s, largely agrees.

“People want to know their neighbor, go to their local park and see the same person,” he said. “Creating that kind of connection is what I see us doing through some combination of digital and print, and as a root and foundation of the community.”

But the long-term viability of Howell’s news outlets, which employ 18, isn’t clear. For now, the 75-year-old publisher says he controls his own destiny, and he’s happy with his business – even though he’s “certainly not getting rich on it.” He’s also bullish about the millennial generation coming up with new methods of providing local news, and believes budding entrepreneurs will eventually carry the torch for locally owned newspapers, although he wasn’t quite sure how.

“I just figured I’d live forever and I’d be all set,” he quipped.

Similarly, Ward doesn’t have a clear plan for his flagship newspaper’s future. He’s content for now, and has a tough time seeing himself ever fully retiring. Ward said he looks forward to the day when he can be the “80-year-old publisher doddering through the newsroom, telling everyone about the old days.”

And while he’d never say “never” to the prospect of an outside media company buying him out, he doesn’t want it to happen and doesn’t like the idea of outside ownership.

“Wall Street doesn’t belong in this industry because local news needs local people, making local decisions, about local stuff,” he said. “You can’t parachute a publisher in from outside.”

Ward has even flirted with the idea of an employee-owned model, known technically as an employee stock-ownership plan, which gives employees a stake in the company.

“If I get to be 80 years old and have millions in the bank, and had some really good people, I’d be ready to turn it over and say, ‘Good luck, manage it,’ ” he said.

Eli Sherman is a PBN staff writer. Email him at Sherman@PBN.com, or follow him on Twitter @Eli_Sherman.