Trinity Briceno, a senior at Cranston East High School, didn’t attend school between December and April.

She was hospitalized in November after students and teachers reported symptoms of carbon-monoxide exposure, including dizziness and nausea. Her mother, Pauline Belal, subsequently held her out of school, accusing officials of not properly testing for the odorless gas. She has since sued the city.

The incident was one of several health or safety issues in recent years at schools throughout the state, where the average age of public-school buildings is 56. The latter is consistent with the 54-year average age of public schools in the Northeast in 2012-13, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

“All of our schools are in deplorable, disgusting condition,” Belal said during a March 22 House Finance Committee meeting.

State lawmakers are considering whether to approve a $250 million bond referendum, which if supported by voters in November would go toward repairing the state’s dilapidated schools. A recent report examining the condition of schools found nearly 90 percent of the 306 buildings were below average or worse. Eighteen need to be replaced.

“We have to do it,” said Gov. Gina M. Raimondo, who has made the effort her top priority this year. “We can’t afford not to.”

[caption id="attachment_209335" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

NEEDED REPAIRS: Pictured are examples of school infrastructure in need of improvement throughout the state, including deteriorated seats and student lockers at Classical High School in Providence and damaged ceiling tiles at Rogers High School in Newport. / PBN PHOTOS/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

The state currently pays about $80 million annually toward school repairs, a piecemeal approach Raimondo likened to paying for Band-Aids. A longer-term answer is needed, she argued, and financing the effort with debt is how she’d like to accomplish it.

“We haven’t done [a school] bond in a long time. Massachusetts has done it seven of the last nine years,” Raimondo said. “We’re behind and we have to get going.”

Borrowing money with bonds is an effective way for a state – especially one with deficits – to make substantial upfront investments in massive infrastructure projects such as school repairs. In addition to the $250 million proposed for this year, Rhode Island is eyeing the possibility of borrowing another $250 million by 2022, bringing the total to $500 million.

The governor’s proposal appears popular with voters. In February, nearly two-thirds of respondents to a poll by the Hassenfeld Institute for Public Leadership at Bryant University said they favored the $250 million bond to fix schools.

But adding hundreds of millions of dollars to the state’s outstanding debt comes with consequences, namely limiting Rhode Island’s ability to use debt effectively to finance future projects.

“We can afford the additional debt, but what that means is that we’ll have to be much keener about setting priorities in the future,” said Gary S. Sasse, director of the Hassenfeld Institute. “If you buy a brand-new car this year, you may not be able to buy a brand-new TV next year.”

Meanwhile, the state in recent years has made strides toward alleviating its debt burden. But it’s historically carried a lot of debt in comparison to other states, and the current school-bond proposal could have some potentially damaging repercussions at the local level, where some communities are struggling with long-term debt and other unfunded liabilities.

“About 20 years ago, Rhode Island was one of the most heavily indebted states in the country,” said Seth Magaziner, Rhode Island general treasurer. “Since then, our level of debt as a percent of the budget and total economy has declined relative to our peers. … We’ve made progress, but we have more work to do.”

UNDERSTANDING DEBT

When a government wants to make big capital investments, such as building new highways or improving seaports, borrowing is a popular financing method.

So popular, in fact, more than 100 debt-issuing entities in Rhode Island had a total of more than $10.5 billion in accumulated debt in 2016, according to a state report.

There are different ways to borrow, but a common method in the public sector is to sell bonds to investors. The debt, plus interest, is repaid by taxpayers over time.

In Rhode Island, the state cannot take on any debt – with some exceptions – exceeding $50,000 without the consent of voters.

[caption id="attachment_209331" align="alignright" width="206"]

DELAMINATED WALL: Jeff Watts, plant engineer at Rogers High School in Newport, examines a problem area at the school, outside the gym, where water has delaminated the wall. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

This November, in addition to voting for governor, mayors and school committee members, Rhode Island voters also will likely be asked whether they want to pay toward millions of dollars in debt to finance big infrastructure projects, such as fixing schools and improving wastewater-treatment facilities.

Since 2008, Rhode Island voters have approved $946.6 million in general-obligation bonds.

These ballot questions, known as referendums, are the trigger to big building projects throughout the state. In recent years, voters have approved similar referendums to pay for improvements to ports, public higher education facilities and brownfield remediation.

With debt financing, however, the devil is in the details, and sometimes it takes years for projects to come together and much longer for the debt, plus interest, to be repaid.

Indeed, Rhode Island in April issued $149.4 million in bonds to pay for a slew of voter-approved capital-improvement projects. About $22.8 million of this year’s payment was earmarked for projects approved by voters dating back to the 2012 election, including $17.8 million for higher education facilities.

Projects get funded when ready, but the state also tries to avoid taking on too much new debt in any given year.

It’s a balancing act, as taxpayers each year pay back old debt, which over time comes entirely off the books. In 2016, Rhode Island taxpayers still owed $203.9 million for the R.I. Convention Center Authority, which oversees the convention center and Dunkin’ Donuts Center.

Debt is a useful method of financing, as it affords governments flexibility to spend more money than otherwise affordable upfront. But like any type of budgeting, if done poorly, it can cost taxpayers much more than what was anticipated.

[caption id="attachment_209336" align="alignleft" width="344"]

Voters approve! Rhode Island voters have approved nearly $1 billion in debt since 2008 and they could be asked to approve another $368.5 million this year. Rhode Island officials would like to borrow the money to pay for repairs of dilapidated schools throughout the state. / SOURCES: R.I. GENERAL TREASURER OFFICE, PBN RESEARCH[/caption]

Taxpayers in 2016 still owed $51.3 million for the Job Creation Guaranty Program, which in 2010 loaned $75 million to the now-defunct video game company 38 Studios LLC. The company went bankrupt in 2012, leaving taxpayers on the hook to pay back bondholders.

Nonetheless, debt as a means to finance is especially popular right now throughout the country because interest rates are historically low, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts.

The challenge for lawmakers – and subsequently Rhode Island voters – is trying to understand exactly how much new debt the government can afford.

“Gauging whether a state can afford to take on new debt … can be difficult,” according to Pew. “As state budgets recover from the effects of the Great Recession of 2007-09, lawmakers are looking for ways to prepare for the next downturn. At the same time, states are increasingly interested in taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow money for key infrastructure projects that may have been put on hold during the recession.”

CAN WE AFFORD IT?

The R.I. Public Finance Management Board last year released a biannual report measuring the state’s ability to assume new debt.

In broad terms, the state’s current level of debt is “generally affordable and within the acceptable levels,” according to the report. Nonetheless, Rhode Island had the 12th-highest debt-services-to-revenue ratio, at 6.4 percent.

The United States median was 4.3 percent, and Rhode Island had the third-highest ratio in New England behind Connecticut (No. 1 in the nation) and Massachusetts (No. 3 nationally).

The major takeaway from the report is that the state should be careful when considering new debt.

The PFMB urged state lawmakers not to take on more than $1.3 billion in debt over the next decade. If the state is successful in borrowing $500 million for school construction, nearly “half the state’s borrowing capacity over the next 10 years would go toward this purpose,” said Magaziner, who heads the PFMB.

In addition to the $250 million for schools this year, Raimondo has also recommended the state borrow $45 million for the University of Rhode Island Bay Campus, $25 million for the Rhode Island College Horace Mann Hall and $48.5 million for a so-called “green bond” for environmental purposes.

If approved by the General Assembly, each bond would be included on November’s ballot. Together, with school construction, voters would be asked to approve $368.5 million in new debt. The average amount approved each election since 2008 totaled $189.3 million.

“You have to look at this as a limiting factor on government spending,” said John C. Simmons, executive director of the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council.

[caption id="attachment_209332" align="alignleft" width="300"]

BETTER SHAPE: General Treasurer Seth Magaziner speaks at a Rhode Island Jump$tart Coalition event at the Statehouse. Magaziner said 20 years ago, Rhode Island was one of the most heavily indebted states in the country. But since then, the level of debt as a percent of the budget and total economy has declined relative to its peers. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

Magaziner, an enthusiastic advocate of the school-construction project, said the PFMB’s original $1.3 billion debt estimate may be conservative, as the state has benefited from locking in lower interest rates over the last few years.

“We have more capacity today than we thought we did a year ago,” Magaziner said.

On balance, the state has paid a sizeable chunk of its money toward interest on general debt in the past. In November, RIPEC released a report examining the state’s spending and measured it against other states. When it came to interest costs on general debt, Rhode Island stood out.

In 2005, general-debt interest costs totaled $294.91 per capita, a common measure to make spending more comparable to other states. The expenditures that year were 15th highest in the country, according to the analysis. A decade later, the cost on debt interest more than doubled to $594.93 per capita and Rhode Island ranked the highest in the country.

The state has since done well to lower its debt payments, and another $1.4 billion is expected to come off the books in the next couple years, but Magaziner acknowledged a need for improvement.

“I’d like to see the overall level of debt moderate in real terms, while still maintaining the ability to issue some bonds to invest in capital projects,” Magaziner said.

According to documents shared by Magaziner’s office with Providence Business News, if the state is successful in adding the school bonds to its debt portfolio, the remaining debt capacity totals about $67.5 million each year beginning in 2020. The amount falls short of the $189.3 million voters have authorized each election and the $149.4 million the state issued this year.

In addition to limiting how much the state can borrow responsibly in coming years, the additional debt could also potentially limit debt already authorized but not yet issued. That is, projects voters approved in past years but that still haven’t received funding.

Additionally, whatever general-obligation bonds state voters approve in the future could potentially be held up for years.

The grand effort to put so much funding toward schools makes clear the Raimondo administration is serious about fixing deteriorating school buildings. It also makes clear the state is willing to forgo – to some degree – future funding flexibility.

“It’s a perfectly legitimate decision to say our priority is fixing up schools,” Sasse said. “When you do that, you just want to make sure your eyes are open. By authorizing this amount of debt, you’re saying that you’re going to forego the opportunity to make debt investments on future and unexpected things.”

[caption id="attachment_209334" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

PRIORITIZING SCHOOLS: General Treasurer Seth Magaziner at a Rhode Island Jump$tart Coalition event at the Statehouse with, from left, Charon Rose, director of outreach, and Nikhol Bentley, financial literacy teacher at Gilbert Stuart Middle School in Providence. Magaziner says the health and safety of students and school buildings have not been prioritized. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

Raimondo and Magaziner stand by the decision.

“For too long the health and safety of our students and school buildings hasn’t been enough of a priority,” Magaziner said. “We are saying K-12 needs to be among the highest priorities for how we use our bond capacity because it has been neglected.”

The effort has also earned the support from some in the business community. Elizabeth A. Suever, a lobbyist for the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, said the Chamber supports the efforts because the workforce is demanding modern workers – who aren’t currently learning in modern spaces. The improved infrastructure also looks good from the outside.

“We believe that investment in school buildings improves the economy and the business climate,” she said. “When businesses are looking to bring workers in from out of state or are thinking about relocating their business from out of state, one of the questions that comes up fairly frequently is, ‘How are your schools?’ We want to make sure we have a great answer for them.”

For policy wonks such as Douglas Hall, director of economic and fiscal policy at progressive-leaning The Economic Progress Institute think tank in Providence, this type of investment into schools makes sense because it’s long overdue.

“I’m not alarmed at the prospect of exhausting 50 percent-plus of bonding capacity for investment in education infrastructure, especially in the wake of decades of neglect,” Hall said.

The borrowing, however, doesn’t end with the state, as cities and towns will be expected to leverage state funds and borrow at the local level to also pay toward school construction. The Rhode Island School Building Task Force last year identified $2.2 billion in deficiencies across the state’s 306 public schools, and more than $600 million was needed immediately to ensure “warm, safe and dry” learning environments.

Some communities have already begun issuing their own debt for school repairs, and most are hoping to take advantage of the state funds when they become available. But unlike the state, Rhode Island municipalities have varying levels of indebtedness. For the ones already struggling, the debt is exacerbated by untenable, long-term liabilities related to retirement benefits.

“When people talk about broken pension systems in cities and towns, they often think about dramatic events [such as] Central Falls [which declared bankruptcy in 2011] and Detroit, but in most cases that’s not what it looks like,” Magaziner said. “In most cases, it’s about pension costs slowly … squeezing out other priorities.”

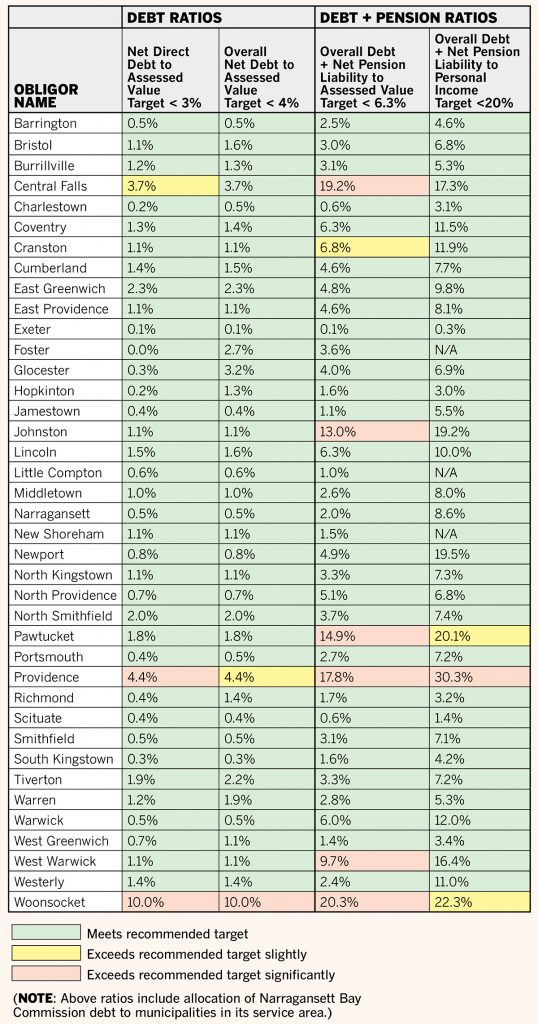

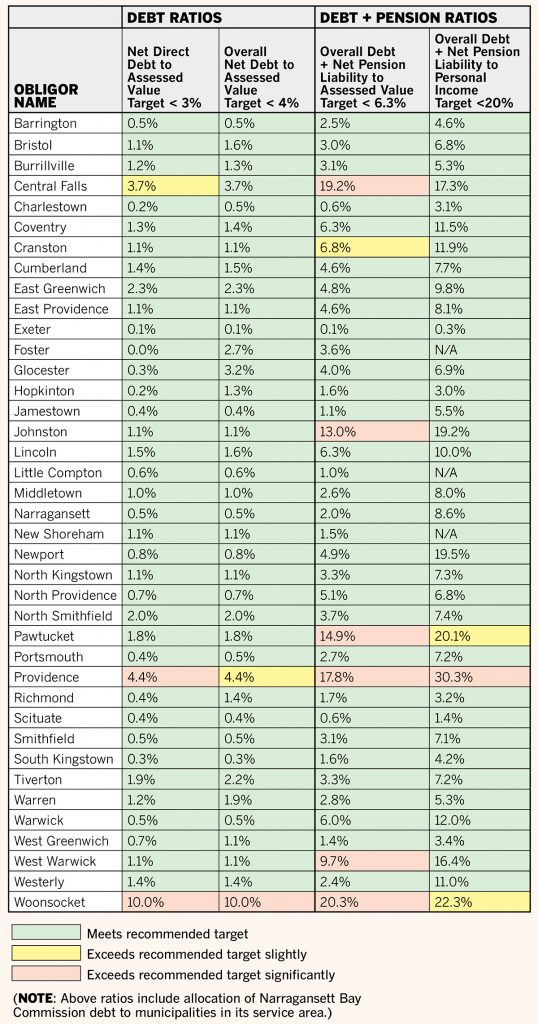

[caption id="attachment_209337" align="aligncenter" width="538"]

Debt and Pension Affordability Ratios for Municipalities: Seven Rhode Island communities exceed recommended targets for indebtedness and pension liabilities. Providence and Woonsocket are among those in the worst shape. / SOURCE: R.I. PUBLIC FINANCE MANAGEMENT BOARD DEBT AFFORDABILITY STUDY[/caption]

CROWDING OUT

For every $100 of taxes in Providence last fiscal year, nearly $22 went toward funding the capital city’s woefully underfunded pension plan.

The $78 million spent on the pension plan last fiscal year is expected to grow to $116 million annually over the next decade, according to a “Report of the Pension Working Group” released by city officials in April. The gap between funding and how much is promised in pension benefits exceeded $1 billion in 2017.

“The unfunded pension liability is Providence’s version of the global warming crisis, an existential threat looming on the medium-term horizon that becomes more difficult to solve with each successive year of inaction,” according to the report.

The pension obligations don’t even include the hundreds of millions of dollars promised for future health care costs, which grow at an alarming rate each year. The soaring expense limits local decision-makers from spending money on other city services, such as school investments.

“You’re absolutely seeing where pension costs are eating up more of the budget and crowding out other priorities,” Magaziner said.

The dynamic is widespread, but more severe in some of Rhode Island’s most populated areas. The PFMB report, for the first time, considered pension liabilities as part of its assessment for how well municipalities could afford debt.

Credit-rating agencies in recent years have also assigned more weight on unfunded liabilities when assessing the credit worthiness of governments, which ultimately affects the total cost of borrowing.

For the most part, Rhode Island municipalities are OK when it comes to assuming new debt, and the statewide effort will be manageable. But some municipalities, including Cranston, are walking a fine line. Cranston’s overall debt and pension liability totaled 6.8 percent of the city’s total assessed value. The PFMB recommends a target rate of 6.3 percent.

Some municipalities, including Central Falls, Johnston, Pawtucket, Providence, West Warwick and Pawtucket, are in rough shape and exceed recommended targets for indebtedness and pension liabilities.

Mike Stenhouse, founder and CEO of the Rhode Island Center for Freedom and Prosperity, a right-leaning, free-market-advocate think tank, says municipal leaders have been careless.

“We believe that localities have been negligent in keeping up the condition of their schools,” he said. “They’ve had plenty of money, in our view, and they’ve not used it wisely. Now they’re going to rely on state taxpayers to solve a local issue.”

Nonetheless, cities and towns throughout the state are moving ahead and issuing new debt to pay for schools.

Providence Mayor Jorge O. Elorza in April unveiled his fiscal 2019 budget, which included a proposal to issue $20 million in bonds to pay for school infrastructure projects. Debt payments, meanwhile, were expected to total $61.8 million in fiscal 2019.

“It’s amazing what you find inside our schools: kids wearing jackets, sometimes you see buckets in the middle of the hallways [catching water],” Elorza said, testifying before lawmakers. “The message we’ve been sending as a city and state is that we’re not investing in our kids the way we should. … This is about taking a quantum leap forward to invest in our kids.”