The last time a U.S. census form arrived in the mail, Marcela Betancur helped her mother fill it out. As a 20-year-old, she had the advantage of eight years of U.S.-based education in English. But her mother still had limited understanding of the written language.

And despite Betancur’s understanding of English, the questions were challenging for her. “Even as a 20-year-old, I was confused about what I had to answer,” she said.

Now, Betancur, who spent much of her childhood in Colombia, is employed as an advocate for Rhode Island’s Latino community, as executive director of the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University. She’s committed to making sure Latinos are represented fully in the upcoming 2020 census.

No single census count may have as much impact locally. For the first time in a century, the state is threatened with a loss of a congressional seat. Prior to 1930, the last time Rhode Island lost a representative, it had a population that justified three seats. The new calculation is not exclusively an issue of Rhode Island’s population, which is stable if not growing, but the swelling size of other states.

To try to stave off the loss of representation and retain federal funds tied to census results, Gov. Gina M. Raimondo has tasked a committee with finding methods to reach individuals and communities that are historically “hard to count” in the official government tally.

These groups include college-age adults, immigrants, the homeless, children, residents with low incomes, and racial and ethnic minorities.

Complicating the challenge, however, is the relatively small amount of state money Raimondo has proposed for the committee in her fiscal 2020 budget – no more than $300,000 – and a potential census question on citizenship that faces a legal challenge due to concerns it could depress immigrant participation. The state and two local communities have joined a lawsuit challenging the question and the U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to decide the issue.

Whatever slim chance Rhode Island has of keeping its two House seats is dependent on ensuring all residents are counted, including documented and undocumented immigrants.

“It’s clear the limited growth we do have in Rhode Island is largely in immigrant communities,” said John Marion, executive director of Common Cause Rhode Island and a member of the committee set up by Raimondo. “It’s important for a lot of reasons, beyond maintaining two congressional districts, that immigrants and all Rhode Islanders be counted.”

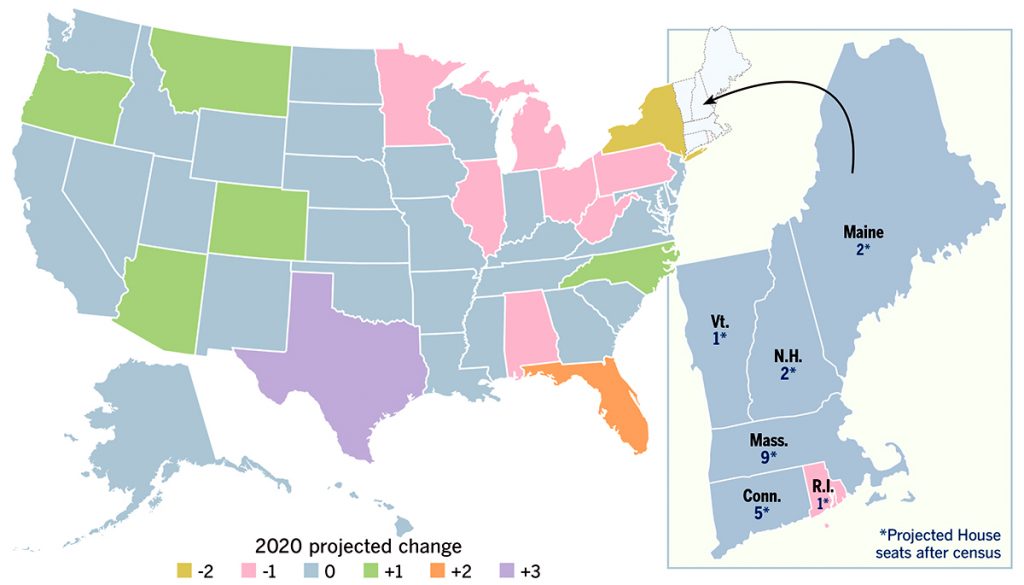

[caption id="attachment_257188" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

ANTICIPATED GAINS/LOSSES IN REAPPORTIONMENT

: Rhode Island is among nine states projected to lose congressional representation in the 2020 census,

based on population changes. New York could lose two seats. Fast-growing states,

such as Texas and Florida, are expected to add congressional seats. / SOURCE: ELECTION DATA SERVICES INC.[/caption]

FEDERAL AID

For the perennially cash-poor Rhode Island budget, federal money is essential for programs tied to state population, including Medicaid, the Head Start education program, school lunches and housing appropriations.

Nationally, $700 billion is distributed annually based on population counts, with funds heading to state, local and tribal governments, said Meredith Brady, associate director of the R.I. Division of Planning. The division handles census data for the Ocean State.

How much Rhode Island could lose, if anything, remains unclear, she says, because the funding is partly tied to the population counts for other states.

But the Ocean State pulls in several billion dollars annually in federal funds based on census counts. A George Washington University analysis found Rhode Island in fiscal 2015 received $3.1 billion in federal funds derived from census statistics. Nearly $2 billion of that was for Medicaid grants.

Neither of Rhode Island’s sitting congressmen, Democratic Reps. David N. Cicilline and James R. Langevin, were available for interviews in recent weeks to discuss the upcoming census and what is at stake for Rhode Island. If the state loses a seat, at least one would be out of a job.

Instead, they issued a joint statement affirming the census count’s importance and potential effect on federal funding.

If the state loses a congressional seat, “one would expect the political landscape to change a lot for 2022,” noted Wendy Schiller, professor and chair of the political science department at Brown University, including an election that year for an open governor’s seat.

“No one wants to stake out their territory on [the 2020 census] just yet because the set of opportunities for 2022 is not yet clear,” she said.

Beyond politics and issues of funding, Rhode Island needs to understand who lives within its boundaries, to better direct services to communities, Brady said.

“One of the issues we really need to understand is how that impacts things. What services may be offered, what is the composition of the population?” she said. “This is all really important to us. It’s not just what is the number. It’s who are the people.”

HARD TO COUNT

Providence Mayor Jorge O. Elorza is worried about the accuracy of the upcoming census. Already, he’s spoken to immigrants – including those here legally – who say they’re afraid to fill out the form. Although he believes the information cannot be shared with other government agencies – such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement – he’s heard both indirectly and directly from immigrants who say they are fearful of participating.

‘We are not declining in population but there is a very real risk that the census will say [that].’

JORGE O. ELORZA, Providence mayor

“I’ve heard it from folks in my own family,” he said. “I have a cousin who is a legal resident, but he heard a lot of noise about this [citizenship] question, at the same time the census form arrived at his house. Never before would he think twice about filling this out. It’s clear it’s making people hesitate on whether it’s the right thing to do or not.”

Elorza is a first-generation American whose parents were undocumented immigrants from Guatemala. He says they later attained citizenship through an amnesty program under the administration of former President Ronald Reagan.

He said while he understands that for immigrants the safest course might be to ignore the census, he’s trying to convince people that it’s in everyone’s interests to be counted. “We’re working against this, in convincing people that no, indeed you are safe and go ahead and fill it out,” he said.

For Providence, a potential undercount of the immigrant population could be significant. The city is disproportionately affected because it is home to many of the people who are considered historically hard to count, but Elorza says no one group, including immigrants, is critical for turnout. Everyone needs to participate, he added, because it’s in everyone’s interest.

“We know from the state of the housing market that people want to live in Providence,” he said. “I know for a fact that we are not declining in population, but there is a very real risk that the census will say we have declined.”

According to the 2010 census, Rhode Island had 1,052,567 people.

That population number has remained relatively flat, according to annual updates. A July 1, 2018, update, based on a community survey, put the Ocean State at 1,057,315 – or 4,748 more people.

About 20 percent of the state population is under age 18. Another 17 percent are age 65 or older.

The ethnic and language diversity of the population is also apparent from the numbers.

The Latino/Hispanic population was 15.5 percent in July 2018. And 13.7 percent of the state residents were foreign-born. Twenty-two percent said they spoke a language other than English at home.

Many of these subgroups are considered hard to reach by the census.

Betancur, who sits on the state’s census committee, said immigrants have historically been undercounted for a variety of reasons. They include educational barriers that make a written form – even in Spanish or another native language – difficult to understand.

If someone doesn’t understand it, they are unlikely to fill it out. “Not only is it their instinct with the census. It is their instinct with most documents or information that comes through the mail,” Betancur said.

Unlike the U.S., many South American and Central American countries have no universal education system for children, or immigrants now living in Rhode Island may have attended school as children but were forced to leave because of economics or violence. It is not uncommon for immigrants to not be able to read the language they speak fluently.

“While they may speak Spanish, the education and linguistic barriers are still there,” Betancur said.

Beyond the issue of literacy, the 2020 census could include a question that asks all respondents whether they are U.S. citizens.

In Rhode Island, Central Falls and Providence, along with the state, have joined in a lawsuit against the U.S. Census Bureau in the Southern District of New York, challenging the inclusion of the question. The suit argues the U.S. Constitution requires a full count of residents, not just citizens, and that the question will depress participation in immigrant communities.

If an immigrant sees the form ask about citizenship status, they may assume the form should only be filled out by U.S. citizens, said Mario Bueno, executive director of Progreso Latino, a nonprofit that provides comprehensive social services to Latin Americans in Rhode Island.

“It just gives the impression that only citizens should respond,” he said. “It’s like, OK, just as if I’m not a U.S. citizen, I shouldn’t vote, maybe I shouldn’t fill out the census as well.”

The organization will help the state’s effort, he said, but for many immigrants, the issue of the census is not front and center, as much as pressing concerns about working, housing and other issues.

At this point, it is not clear if the question will appear on the 2020 census. Although it was ordered removed from the census in a decision in federal court, the office of U.S. Secretary of Commerce has appealed the decision, and five other cases challenging the legality of the question are pending. The U.S. Supreme Court stepped in and plans to hear arguments in April, according to The New York Times.

For other “hard-to-count” groups, the barriers are varied.

College students who live away from home are expected to participate in the census where they live. So, for example, if they live in an apartment off-campus, that is their official location. Similarly, prisoners are counted at the site of the jail.

Because college students move frequently, they are often undercounted in the U.S. census. And Rhode Island, which has 12 universities and colleges, had nearly 80,000 college students last year.

Homeless individuals, by definition, are frequently moving and difficult to count.

[caption id="attachment_257274" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

GRASSROOTS EFFORT: Central Falls Mayor James A. Diossa, left, speaks with Samuel Ogundare, business outreach and public relations coordinator. Diossa said the onus is on communities to help residents understand the importance of filling out the 2020 census, adding that canvassing and a grassroots response may be more effective than a media campaign. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

RAMPING UP?

Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Health, along with Central Falls Mayor James A. Diossa, are leading the state’s efforts to get a complete count, as co-chairs of the Rhode Island Complete Count Committee.

The body, created by an executive order, is among dozens created by states and cities in the U.S. in the past several months. New York, Seattle and Salt Lake City are among the cities. California, which faces the prospect of losing a congressional seat for the first time in its history, has created a statewide committee.

The Rhode Island committee, which started meeting in February, is tasked with developing and coordinating an outreach program to reach the traditional, hard-to-find populations, increase awareness of the need to participate and motivate residents to do so.

The structure is by design a public-private partnership, according to the committee leaders, with funds coming from the state and private contributions. Under Raimondo’s proposed budget, Rhode Island is expected to commit $300,000 to the census effort, with about half going to salary and benefits for an additional data analyst.

Though this is the first time a Rhode Island governor has recommended spending money on the census, according to Marion, other states are expected to spend much more. California, for example, has already appropriated $100 million for its Complete Count effort, with nearly half of it scheduled to go to a public media and marketing campaign. In 2000, California allocated $25 million toward assuring a complete census count.

A calculator created by the Center for Urban Research at The Graduate Center/City University of New York, the Fiscal Policy Institute, State Voices, and The Leadership Conference Education Fund indicates that, based on the Rhode Island population and its “hard-to-count” communities, the state should be spending more than $1 million.

“We’ll be advocating for additional monies,” Marion said. “We think there is a strong argument to be made there is a big return for the state.”

‘The limited growth we do have in Rhode Island is largely in immigrant communities.’

JOHN MARION, Common Cause Rhode Island executive director

Alexander-Scott said private funds will also be used, from the Rhode Island Foundation and other philanthropies, but she could not say how much would be needed.

Among others, the United Way of Rhode Island and the Grantmakers Council of Rhode Island are involved in the local census count.

“This will absolutely be a public-private partnership,” Alexander-Scott said. Through private contributions, the Rhode Island Foundation has hired a consultant, Christine Harley, of 2020 Consulting, to work with the committee.

POWER SHIFTS

Rhode Island has a daunting deficit to overcome if it wants to retain its seat. By the calculations of one Washington, D.C.-area apportionment expert, the state will need to count as many as 38,000 more residents in the 2020 census to keep its second congressional seat.

When asked if the state has a chance, with its Complete Count effort, Kimball Brace, president of Election Data Services Inc. of Manassas, Va., said the issue is more complex.

It isn’t just who Rhode Island turns out and counts. It’s how well the state fares against other states with the same mission.

In addition to Rhode Island, as many as eight other states could lose representation based on anticipated census counts. In the Northeast, they include New York and Pennsylvania. Midwestern states of Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota also face losses.

States seen gaining power include Arizona, Colorado, Florida, North Carolina and Oregon. Texas could gain three more seats.

The apportionment is completed with a mathematical formula, which factors in a state’s population as the 435 total seats in the U.S. House are distributed. Initially, every state gets one seat. Thereafter, the districts are assigned on a rotating basis, depending on the remaining population once the seat has been taken.

Rhode Island, which started with one seat after the first census, in 1789, then grew to two representative seats for the next century. In 1910, the swelling population of the state pushed it briefly to three. Rhode Island went back to two representatives in 1930 and has remained so since.

‘You are looking at 50 percent-less representation [in the House].’

KIMBALL BRACE, Election Data Services Inc. president

The shifting sands reflect movements in American population, and general trends over time. The movement of population away from the Northeast and Midwest to the sunnier climates of the South and West began in the 1930s, Brace observed.

For political impact, going from two seats in Congress to one is significant for Rhode Island, he said. While California may lose a seat, it still has 52 people in the House.

“You are looking at 50 percent-less-representation capability,” he said.

And will the remaining office be granted more funds, to add staff for a statewide office? “Nope,” Brace said. “It’s just gone.”

Marion says it is unlikely Rhode Island will hang onto the second seat, based on growth in other parts of the country. But beyond that, participation in the census is critical for proper allocation of local representatives and understanding of the state’s demographics.

“Imagine that immigrant communities in Central Falls, Providence and Pawtucket are undercounted,” he said. “That is going to shift political power to suburban and rural communities.”

Diossa, whose city is among the most diverse in Rhode Island, said the onus is on communities to help residents understand why the census is so important to fill out. A media campaign may not be the answer, he said, but rather old-fashioned canvassing and a grassroots response.

“Because previous census counts have happened, we’re aware that there are some hard-to-count populations in the state that are going to need special strategies to get these folks – the LGBTQ, the homeless population, college students, the immigrant population – to fill out the questionnaire,” he said.

Through his contacts with the community – he’s a son of Colombian immigrants – Diossa said that, like Elorza, he knows many immigrants are skeptical of sharing any information with the U.S. Census Bureau.

“That’s the role of mayors and councils. Because we have a close connection to our communities, they trust us more,” he said. “Our push is going to be that this is important to fill out because it will impact school aid for the kids, health care funding and infrastructure. And for me, as mayor, it’s critical to know how many residents are living in our city, to assure I’m providing the right allocations in our budget to meet the basic needs of our constituencies.”

Mary MacDonald is a staff writer for the PBN. Contact her at Macdonald@PBN.com.