Many people have never heard of the Rule 12b-1 fee, but it took an $11.8-billion bite out of investors’ assets last year – and if you ever have invested in a mutual fund, you probably paid your share, too.

Now, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is considering overhauling or eliminating the fee, which was started in 1980 as a way for fund companies to cover their marketing costs when the industry was struggling to survive.

The problem, investor advocates say, is the now-thriving $11 trillion mutual fund industry has found different uses for the little-known fee, such as paying operating expenses and compensating brokers and financial advisers.

But the mutual fund industry says the fees are essential since they also pay for services provided to shareholders, such as financial advice and the distribution of prospectuses.

The SEC has spent recent months collecting public comments on the Rule 12b-1 fee, and an agency spokesman said last week that staff members are formulating a recommendation to be presented to SEC Chairman Christopher Cox by year’s end.

In the meantime, the SEC’s pending decision has sparked a debate in the financial planning world over the future of the fee, according to Hakan Saraoglu, a finance professor at Bryant University.

At the very least, Saraoglu said, mutual fund shareholders would benefit from better explanations of the 12b-1 fees, including a clear breakdown of where the money is going. “They need to have more transparency,” he said. “Right now, it’s almost like loads in disguise.”

Why should the average investor care?

Depending on the fund, the Rule 12b-1 fee typically ranges from 0.25 percent of a fund’s assets to 1 percent. In other words, on a $10,000 investment, the charge is between $25 and $100 a year.

But those small costs add up over time.

A $10,000 investment in a mutual fund with an expense ratio of 0.5 percent that has an 8-percent annual return will leave a shareholder with $60,983 after 25 years. The same investment with a 1-percent expense ratio would be worth $54,327, or about 11 percent less.

“There are real cost issues that people ought to be aware of and concerned about,” said Barbara Roper, director of investor protection for the Consumer Federation of America. “They ought to understand what they’re paying so they can make a judgment on whether they are getting the appropriate return on the investment.”

It was 1980 when the SEC enacted Rule 12b-1 fees as a way to let mutual fund companies use a small portion of their shareholders’ assets to market and advertise their funds. The thinking was that funds would grow, and that would benefit investors by improving the economics of scale.

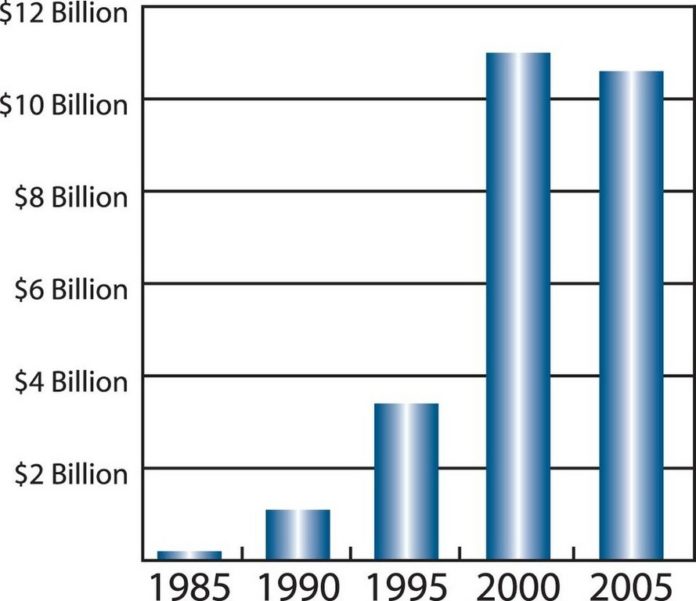

At the time, the mutual fund industry had about $44 billion in assets. In 1985, 12b-1 fees amounted to $200 million industrywide, according to the Investment Company Institute, a national association of investment companies. By 1995, the fees amounted to $3.4 billion, and in 2006, they were $11.8 billion.

As the industry expanded over the years, the use of the 12b-1 fee changed as well.

According to a study conducted by the Investment Company Institute, only 2 percent of the 12b-1 fees in 2004 were dedicated to promotion and advertising, while 92 percent of the money was used to compensate brokers and financial advisers for their initial assistance and ongoing shareholder services.

Saraoglu said many funds that already have upfront charges, called loads, to compensate brokers and advisers also have 12b-1 fees. Many times, shareholders of funds touted as “no load” are subject to 12b-1 fees as well. And some closed-end funds – ones that don’t accept new shareholders and would have little need to promotion – still have 12b-1 fees tacked on.

Not that the average investor has noticed, Roper said.

“The fees are essentially hidden from view, at least for the unsophisticated investor,” she said. “Even those who read a prospectus would have little clue what it was used for.”

Edward Giltenan, a spokesman for the Investment Company Institute, disagrees that the fees are hidden, noting that they are included in a mutual fund’s published expense ratio and are spelled out in fund literature elsewhere.

“If it’s hidden, it’s hidden in plain sight,” he said.

While the ICI supports a “refinement” of the 12b-1 fee, Giltenan said the fee is indispensable because it funds services that shareholders need: investment advice. “Most people need some kind of advice, whether it’s at the time of initial purchase, or ongoing handholding,” he said.

But Roper argued that it makes more sense for a fee to be paid by the investor directly to financial adviser. “Then the investor understands how much they’re paying and why,” she said.

That’s how Donald Clarke operates.

A financial adviser for Arlen Corp. in Providence, Clarke said he doesn’t accept 12b-1 fees, opting instead to charge clients through flat fees based on the amount of assets under management.

“We look at it as a differentiator,” he said last week. “The clients know what they’re paying, and it just adds another layer of trust.”

“It’s about time the SEC looked into the lack of transparency [of 12b-1 fees],” Clarke added. “I say do away with them.”

The Consumer Federation of America isn’t ready to advocate for that. Roper said the group is suggesting that the SEC take a broader look at reforming broker and adviser compensation methods because there are other financial products that have similar little-known fees.

“The mutual fund companies have a legitimate concern – that brokers will discriminate against their products if the compensation is made more transparent in that one area,” Roper said. •

No posts to display

Sign in

Welcome! Log into your account

Forgot your password? Get help

Privacy Policy

Password recovery

Recover your password

A password will be e-mailed to you.