Over the past eight years, Providence Student Living Capital LLC has purchased and renovated more than 100 residential structures in Providence, mostly multifamily units.

And moving into those apartments, for the most part, are college students.

Dustin Dezube, the company owner, rents about 380 beds among his 120 units. Many of his apartments are expansive and newly renovated and are leased to four or more students living together. Are they bad neighbors? Dezube doesn’t think so.

“I can count on my hands the times that neighbors got upset. One time, the police were called,” he said. “I’ve been doing this for eight years. It’s just not a common thing.”

Yet in Providence and across the state, communities are looking at new ways to regulate where students can live and in what numbers, as well as imposing steep fines for throwing disruptive parties.

Providence has a three-student cap for single-family homes, in single-family zones, and is looking at expanding that to other kinds of structures in the same areas, even as the original ordinance is being challenged before the state Supreme Court.

Narragansett, which had a similar ordinance restricting rental houses to no more than four unrelated people, had its requirement overruled in court and is waiting to see what happens with the Providence case.

Over the years, the seaside town has become the home of choice for University of Rhode Island students, who occupy as much as one-third of the town’s housing stock, according to Town Manager James Manni.

Bristol, home to many Roger Williams University students, has a longstanding ordinance that limits households to four or fewer unrelated persons, but that hasn’t been challenged as similar language was in Narragansett. State law allows towns to regulate how many “unrelated” people can share a household, and Bristol has had that limit in its definition of household since 1986, as have many communities in Rhode Island, said Andrew Teitz, a partner at Ursillo, Teitz & Ritch Ltd., who is the assistant town solicitor for Bristol. His firm represents several communities, including East Greenwich, West Greenwich, South Kingstown and Barrington.

Bristol leaders have focused more effort in recent years on disruptive student house parties, or behavior, than on student-related zoning or housing issues.

“It comes down to the issue of what is the problem,” Teitz said. “In Bristol, the problem is more the ‘party house’ than the removal … of housing stock.”

[caption id="attachment_250660" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

STANDING UP: Attorney Leonard Lopes represents homeowners who want to limit the number of college students in Providence who can live in homes originally built for families. / PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

BAD NEIGHBORS?

In Providence, the idea is to hold out the single-family, middle- to upper-middle class neighborhood as something to be protected, specifically from undergraduates and from landlords who would add density to buildings.

First sparked in 2015 by house parties thrown by students living in Elmhurst, near Providence College, the current effort to limit the density of students in apartment buildings or homes originated on the East Side, near Brown University.

On Keene Street, a residential area of large, elegant homes, a landlord purchased two Victorian-era structures over the last two years, according to city real estate records. Each of them is a two-family home. By 2018, a copy of a lease for 13 students had been obtained by a neighbor for one of the houses. It isn’t clear if the students ever moved in.

Now the residents of this area are represented by Providence-based attorney and lobbyist Leonard Lopes, who for the past year has advocated a policy of stricter rules on how many students can move in together.

Lopes said the issue is about neighborhood character, and it’s happening across the city. The problem is that students are behaving in ways that are inconsistent with people who live in single-family, residential zones, he says.

“When you have young people living together for probably the first time without direct, parental supervision, at times their behavior can be disruptive to the neighborhood,” Lopes said.

Parking, noise, littering, increased activity – all can be problematic. “Which is outside the character of what the neighborhood contemplated,” Lopes said. “The reasons why the city has these zones is to provide a particular character, and what I call an owner’s expectation of the kind of neighborhood he or she wants to live in.”

His clients, organized as the Concerned Citizens of Providence’s East Side, want their city to enforce the zoning laws. In their case, on Keene Street, the structures that were purchased are legal, two-family homes, and so wouldn’t have had to comply with the existing city regulation capping student rentals at three people.

But the idea of 13 students in a house once occupied by a family or two, has mobilized neighbors. Several yards have blue protest signs that tell the city to enforce its zoning.

“My clients are respectfully clinging to the notion that rules and laws matter,” Lopes said. “What’s happened is this sort of activity has galvanized them. … They are not shrinking violets.”

The property owner who purchased the Keene Street properties, Walter Bronhard, declined through his attorney to be interviewed. His Cranston-based attorney, John J. Garrahy, of Garrahy Law LLC, also declined to be interviewed.

But Garrahy has attended all of the meetings of the City Plan Commission subcommittee, which met several times over the past year to determine how to expand the restrictions on student leases.

The subcommittee, after considering various forms of regulation, ultimately recommended that the same three-or-fewer prohibition now in place for single-family homes, in single-family zones, be extended to all dwellings in the city’s single-family zones.

On Jan. 15, the CPC agreed to recommend that the City Council adopt the new zoning standard.

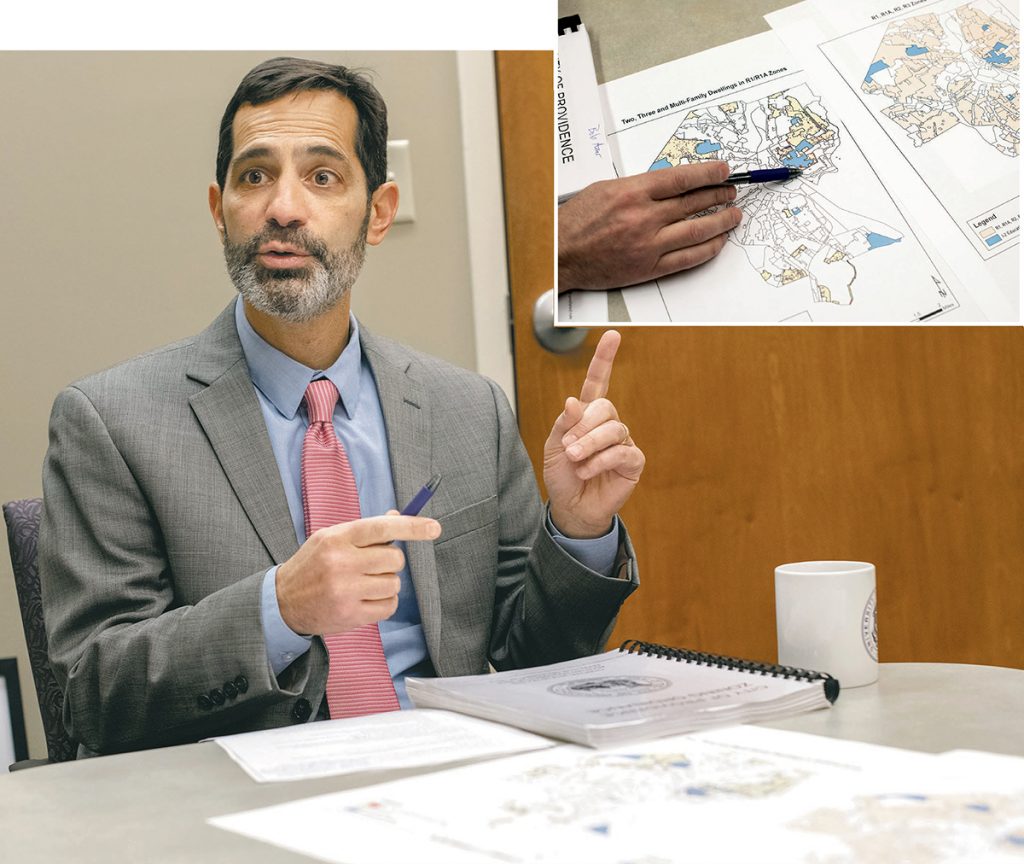

If approved, this would expand the current ordinance, which affects 7,000 single-family homes, to another 1,800 two-family, triple-family and multiunit structures, said Bob Azar, deputy director of planning and development for the city. The additional restrictions would be grandfathered in, so existing properties that already rent to students would not be affected.

[caption id="attachment_250617" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

REGULATION GAPS: Bob Azar, deputy director of planning and development for Providence, points out on a few maps where the current city regulation of three students per single-family house in a single-family zone has gaps.

/ PBN PHOTOS/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

Azar initially recommended a stronger prohibition – expanding the three-student cap to all structures in single-family zones, as well as multifamily zones.

It would address the issue of student density in dwellings, because it is not unusual to have multifamily zones immediately around the universities and colleges, he said.

“If you think this issue of high density of students is problematic in the vicinity of campuses, then you have to consider the [multifamily] R2 and the R3 zones,” Azar said. “At the end of the day, where they ended up going, is they feel the [single-family] R1 zones should be treated differently.”

Harry Bilodeau, owner of Bilodeau Property Management Inc., is a City Plan Commission member. He said Providence has to protect its single-family neighborhoods.

He recommended an expansion of the restrictions to cover the various kinds of housing throughout the single-family zones, which are located in several neighborhoods but clustered around Brown and PC.

“I’m trying to protect middle-class housing,” Bilodeau said. “I want to make sure that upper-class and middle-class housing and the population that lives in those houses continues to live in Providence.”

Bilodeau lives in a multifamily unit. He is not anti-student, he said. But the single-family areas are under pressure from landlords who want to maximize profits by renting to students, a growing population in Providence. If a large house is cut up into rooms for 10 students, he said, using a theoretical example, that property could generate up to $1,200 a month from each of those students, or $144,000 annually.

“And suddenly you’re sitting there saying holy mackerel,” Bilodeau said. “It can really distort things.”

‘Warehousing 13 students in a one-to-two-family home … puts profits over people.’

LEONARD LOPES, Providence attorney

For Lopes, the issue is about striking a balance that allows landlords to rent to people but doesn’t unduly burden residential areas.

“I would certainly say that warehousing 13 students in a one-to-two-family home and making in excess of, let’s say, $200,000 annually in rent, puts profits over people,” he said.

In addition to putting a limit on student density, the city wants to require greater accountability from the universities and colleges.

As part of the ordinance, the Providence-based schools would be required to inform the city of how many students are living off-campus each year and explain how they are communicating the city’s zoning regulations to them. In addition, universities would have to have a clear process for city residents to file a complaint about off-campus behavior.

That information is not required to be supplied now, said Azar, although some universities have done so.

According to his data, Providence had about 3,000 undergraduates living off-campus last year. About half were enrolled at Brown.

Providence College reported it has 679 students living off-campus this year, which is an increase over the past decade, when the numbers averaged at slightly more than 600, but a marked decline from the 1980s.

In 1988, the peak year, PC had 1,298 students living off-campus. A sudden drop in the mid-1990s probably reflected the opening of on-campus housing, according to Azar.

Providence isn’t the only community in Rhode Island struggling with how to manage off-campus student populations.

‘VERY POLARIZING’

[caption id="attachment_250616" align="alignright" width="212"]

EXPANSIVE APARTMENTS: Dustin Dezube is the owner of Providence Student Living Capital LLC, which has purchased and renovated more than 100 residential structures in Providence, mostly consisting of multifamily units that are leased to four or more college students living together.

/ PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY[/caption]

Narragansett has waged among the most sustained efforts to control off-campus housing choices.

After URI students started moving in greater numbers into single-family developments in the 1990s, Narragansett adopted an ordinance that sought to limit the number of “unrelated people” living in rental houses. The most recent definition, of four or fewer, was rejected as unconstitutional in a recent Superior Court challenge.

Although the town could appeal, to be efficient it is waiting to see what happens in the Providence court case, which is pending before the state Supreme Court, because the legal issues are similar, said Manni, the town manager.

The issues around students living in communities originally developed as single-family suburbs have been divisive. “It’s a very polarizing issue in town,” Manni said.

As a state police trooper, he sat on a task force that looked into student disruptions statewide. Among the communities, Providence and Narragansett had the most issues.Narragansett, which has 15,000 residents, has as many as one-third of its properties being used as rentals. In the winter, many are occupied by students.

Short of enforcing the number of occupants per home, police are using a $500 ticket and a bright orange sticker to put a damper on student parties. If students have a house party that is disruptive and draws police, the front door has to carry an orange sticker.

Police issued 74 stickers for disruption in 2018, Manni said, adding student disruptions appeared to have leveled off. “Over the last several years, the issues with students have become better,” he said.

In Providence, in 2015, after a series of disruptive house parties near Providence College, the city used the term “students” in its ordinance and limited them to three to a house in single-family zones.

Challenged by an attorney on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island, the zoning regulation was upheld in Superior Court in 2018 but has been appealed to the state Supreme Court.

‘[Student housing] is a very polarizing issue in town.’

JAMES MANNI, Narragansett town manager

While the city celebrated the ordinance being upheld in Superior Court, residents say it has not been enforced.

Critics of the ordinance say it’s difficult to enforce.

Jeffrey Levy, a cooperating attorney for the ACLU who filed the lawsuit against the city in 2016 on behalf of a property owner and four tenants, said the city is discriminating against students. It is treating them as second-class citizens, he said.

“Do we want to make it easier for kids to go to college and afford to live in Providence? Or do we want to make it harder?” Levy said.

Other cities are moving in the opposite direction and encouraging development of multifamily housing. Minneapolis, Levy said, has removed single-family zoning.

The proposal to identify only undergraduates, for example, removing the “graduate students” from the definition, is arbitrary as well, he said.

“It all is very arbitrary,” he said. “What if I’m 43 and decide to go back to get my degree?”

The prospect of restrictions expanding to multifamily houses has sent a chill through landlords who are active in the Providence market.

Dezube, for example, said once the subcommittee agreed to pull back from the multifamily zones, he felt some relief. But he’s still nervous, because the policy is in play.

Most of his units are in multifamily buildings. “That would have had significant ramifications for my business,” he said, of the broader approach. “I’m very apprehensive. … It would really impact anyone who wants to rent to students.”

That broader issue – of regulations that chill future investment – is something the city should be wary of, said Nicholas Hemond, a partner at DarrowEverett who represents the owners of 02908 Club, a Providence company that owns and leases 125 properties near Providence College.

Most of the 02908 holdings are in a multifamily zone, and most are multifamily structures, Hemond said. The aesthetic appearance of the areas where the company has invested is “a world away” from where they were 20 years ago, said Hemond, who lives in and grew up in Elmhurst.

As a company, 02908 Club has not packed students into buildings. “His practice is to limit it on his own, to one student to one bedroom,” he said of Robert McCann, one of the principals.

His client favored a regulation that would have reflected how many bedrooms are in the units. “It seemed crazy to say to someone, you own a house with five bedrooms, but you can only have three people living there.

“Restricting the number of people who live in a house does absolutely nothing at midnight on a Friday, when 4,000 kids who live on campus pour into the neighborhood for parties,” Hemond said.

‘It’s fundamentally wrong to discriminate against people on the basis of their status.’

SETH YURDIN, Providence city councilman

Seth Yurdin, a Providence city councilman who represents student-heavy Fox Point and other East Side neighborhoods, said he hasn’t received pressure from property owners to rein in students.

He hasn’t seen the City Plan Commission’s recommended zoning change but is opposed to any regulation of student housing via zoning.

The Fox Point neighborhood is filled with students, he observed. Universities have become more responsive and behavior can be managed through other means, he said.

“I think it’s fundamentally wrong to discriminate against people on the basis of their status,” he said. “Whether it’s constitutionally protected or not … I don’t see that it makes sense looking at what people do and deciding where they can live.”

Mary MacDonald is a staff writer for the PBN. Contact her at Macdonald@PBN.com.