[caption id="attachment_250655" align="alignleft" width="165"]

Edinaldo Tebaldi[/caption]

The end of the Great Recession has been followed by a slow but steady economic expansion that led to a significant drop in unemployment rates across the nation, particularly across New England states.

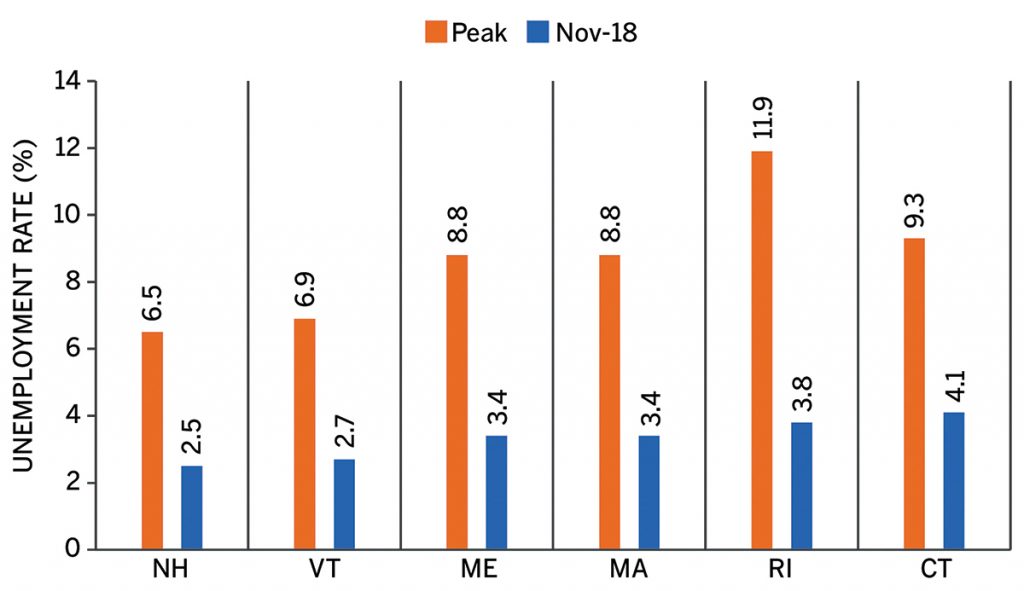

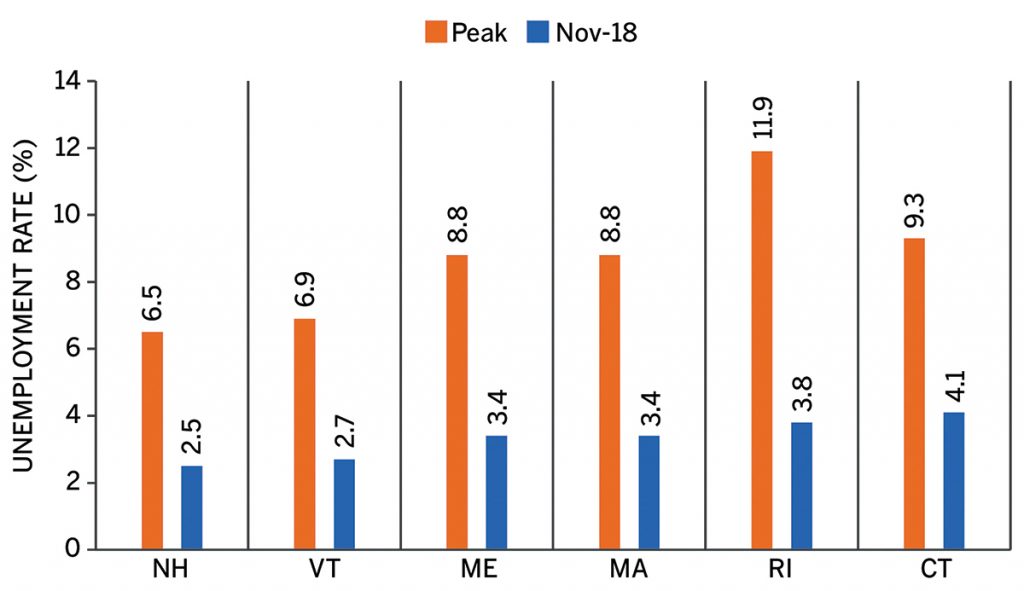

As of November 2018, the unemployment rate was 2.5 percent in New Hampshire, 2.7 percent in Vermont, 3.4 percent in Maine, 3.4. percent in Massachusetts, 3.8 percent in Rhode Island and 4.1 percent in Connecticut. These unemployment rates contrast with much higher peak rates during the economic downturn in which the unemployment rate peaked at 11.9 percent (March 2010) in Rhode Island, 9.3 percent (November 2010) in Connecticut, 8.8. percent (January 2010) in Maine and Massachusetts, 6.9 percent (June 2009) in Vermont, and 6.5 percent (August 2009) in New Hampshire (See Figure 1).

[caption id="attachment_250642" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

Figure 1: Current unemployment rates are significantly lower than those during the 2008-09 economic meltdown. / Source: Authors’ compilation using data

from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[/caption]

Unemployment rates are, however, made of three components: cyclical (due to business cycles), frictional (normal unemployment due to people changing jobs) and structural (long-lasting unemployment due to the structure of the economy).

Frictional and structural unemployment change very little during economic cycles. Cyclical unemployment, however, increases during recessions and becomes negative during economic booms that take the economy above its full-employment level.

[caption id="attachment_250641" align="alignleft" width="158"]

Hannah Sheldon[/caption]

Economists believe that when cyclical unemployment is zero, the labor market is in equilibrium and the economy has reached its natural unemployment rate, is at full-employment and is efficiently allocating resources.

If the unemployment rate falls below its natural level, employers will struggle to find new employees unless they increase wages, which increases costs that are passed on to prices, leading to inflation. Economists, thus, believe that an economy cannot sustain the unemployment rate below its natural level for extended periods of time.

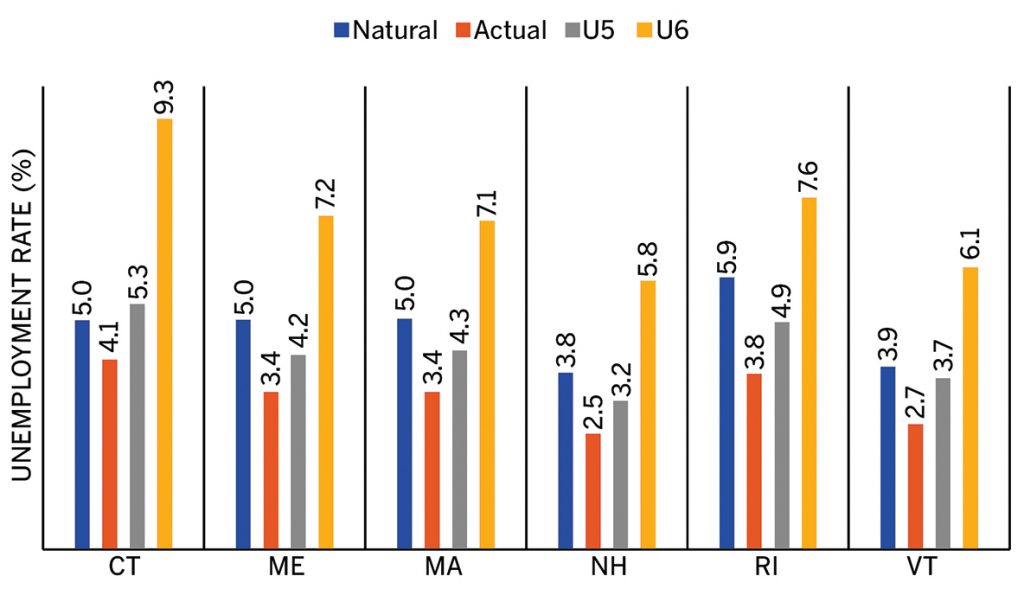

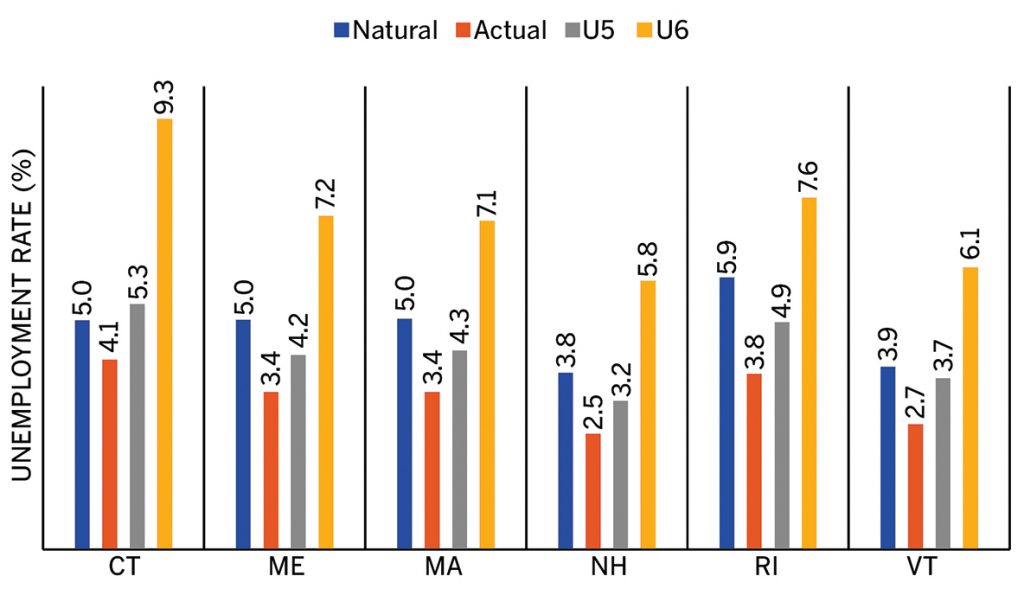

The U.S. economy is operating below its natural unemployment level. According to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, the natural rate of unemployment for the United States is 4.6 percent, compared to a current unemployment rate of 3.9 percent. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office does not provide estimates of the natural unemployment rate for states. We estimate the natural unemployment rate for all New England states utilizing standard methods.

We also find that the current unemployment rate is below its natural level for all new England states. The natural unemployment rate is estimated at 5.9 percent in Rhode Island, 5 percent in Connecticut, Maine and Massachusetts, 3.9 in Vermont and 3.8 in New Hampshire.

In principle, this indicates that the unemployment rate is below sustainable levels in all New England states. That means it will either eventually increase to bring the labor market to equilibrium, or if the unemployment rate remains lower than its natural level, wages and prices will increase, leading to inflation.

There is, though, another possibility: the labor market is neither too hot nor on the brink of reversing course because the standard measure of unemployment underestimates unemployment.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics provides several alternative measures of unemployment, including the U5, which includes the unemployed, plus discouraged workers and marginally attached workers, and the U6, which comprises U5 plus workers who are employed on a part-time basis because of economic reasons (are usually not counted as unemployed).

The chart below (Figure 2) shows that the U5 is also below the natural unemployment rate for most New England states, except Connecticut. The U6, the most comprehensive measure of unemployment, however, is higher than the natural unemployment rate for all New England states. Current U6 rates are lower than those the rates observed in 2006-07 (except in Connecticut).

[caption id="attachment_250643" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

Figure 2: Alternative measures of unemployment, November 2018, New England states. / Source: Authors’ compilation using data

from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[/caption]

All measures of unemployment clearly show that the labor market has improved significantly in New England. There is also a high probability that the unemployment rate has reached a trough (lowest observed level) and is below its natural or full-employment level. The key implication from this observation is that unemployment is likely lower than the rates that can be sustained without causing wage and price inflation. This does not imply that the labor market will quickly deteriorate, but instead that corrections will likely take place in the near term, including wage increases that could trigger inflation and a hiring slowdown.

The ghost of cost increases is already here: according to the Labor Department’s employment cost index for civilian workers, wages increased 2.9 percent from September 2017 to September 2018, the biggest increase since 2008. n

Edi Tebaldi is a professor of economics at Bryant University. Hannah Sheldon is an economics student at Bryant.