In one of the most historically intact neighborhoods in the United States, survival is measured in inches and feet.

The front line of the neighborhood in its battle with the rising ocean is Marsh Street. As the name implies, it originally faced an inlet and marsh, which were filled gradually for commercial purposes between 1860 and 1895.

As a result, not only does The Point, a more than 400-home, historic neighborhood on Newport Harbor, face flooding from the sea, but from its own surroundings. Sea-level rise, increasing intensity of storms and more than 200 years of upland development all contribute to the water infiltration that threatens it.

Already, a good soaker on a high tide sends water into its streets. And climate change-induced, sea-level rise doesn’t bode well for much of the neighborhood, according to maps compiled by the University of Rhode Island, through several affiliated organizations.

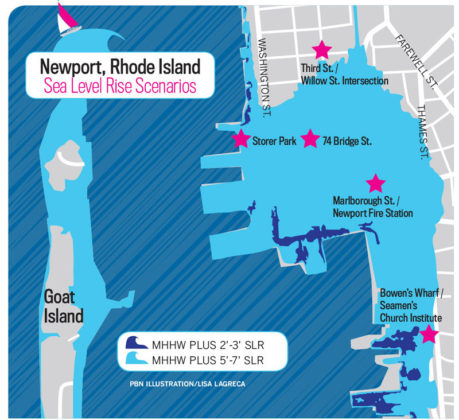

They predict that by 2100, much of the Colonial neighborhood could be submerged if recent models for sea-level rise come to pass. Under a sea-level rise scenario of 5-7 feet of higher high tides, almost half of the neighborhood would be underwater.

In December, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration came out with new projections for the Northeast, based on acceleration of ice loss in Antarctica and Greenland, said Grover Fugate, executive director of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council. On the high end, sea-level rise by 2100 could reach 9.8 feet for the Northeast, he said.

“It’s going to be underwater,” Fugate said, referring to the swath of blue on the projection map, which extends from the harbor up to Willow Street. “If it’s blue in color, it’s going to be underwater.”

And residents of The Point are not the only ones whose historically significant property is at risk.

Melissa Barker, a GIS coordinator for Newport, in August 2015 used the satellite technology to map all of the threatened historic properties for Newport, Bristol and other coastal communities in Rhode Island.

The project was partially funded by the R.I. Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, because state preservation officials are also concerned, and wanted to understand the extent of the problem.

Barker’s work indicates that 21 communities in Rhode Island are affected, including approximately 2,000 properties that are listed or eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. She did not consider sea-level rise projections, but the historical record for storms and rainfall contained in the Federal Emergency Management Agency mapping.

Of the communities she mapped, Newport has by far the most historical properties that are threatened by coastal flooding. It had 548, more than one-quarter of all inventoried in the state.

And many of those properties are hampered not only by their proximity to the water, but construction or renovation restrictions designed to protect the historic character of the properties and neighborhoods they are part of.

MAINTAIN OR PROTECT?

In any other neighborhood, homeowners might safeguard their property and investments by choosing to raise their houses by several feet above the flood line, defined as the “mean higher high water line,” or modify them to better protect them from flooding.

But in a historic district, physical alterations that change the exterior of a home are often discouraged, if not blocked, because they could ruin the historic integrity of the property, and surrounding neighborhood.

This is one of the central challenges facing the neighborhood, and all historic coastal neighborhoods, says Teresa Crean, coastal manager for the URI Coastal Resources Center, which with several partner organizations produced a series of inundation maps that reveal what scientists say the future holds for the neighborhood.

“What’s more important? Maintaining the historic integrity of your building or protecting it from flood damage?” she said. “And is there a happy medium where you … still recognize that these historic structures tell a story, and are part of our cultural fabric, but we’re also modernizing it, keeping up with the times and current risks?”

In recent months, the city has started the process of coming up with what might become a happy medium: design guidelines. The purpose is to advise owners of historic houses, as well as the Newport Historic District Commission, which makes decisions on requests to alter structures within the districts, said Helen Johnson, the historic-preservation planner for Newport.

“We want to maintain the historic integrity of these houses,” Johnson said. “We want to maintain the historic integrity of the streetscape. But we recognize homeowners want to protect their properties.”

The future of the neighborhood has come under increasing scrutiny. Last April, led by the Newport Restoration Foundation, city and federal officials, historical planners, preservationists and neighborhood residents participated in a conference, Keeping History Above Water, to draw attention to the issues of flooding and sea-level rise, and take steps.

One of the most dramatic responses is to elevate a structure, to literally raise it up above the flood line.

Since 2014, two property owners in The Point have received approvals from the city to do so, according to Johnson.

In one instance, the lot is large enough that the house can be moved back, away from the street to accommodate a new, elevated entrance. In another instance, the homeowner had requested a higher elevation for the house than was ultimately allowed by the Historic District Commission.

KEEPING ABOVE WATER

The Point was originally laid out by the Quakers about 1725. Its name refers to a point that once stuck out into Newport Harbor, when a coastal cove at the southern end of the neighborhood still existed.

That cove, filled for commercial development, is now roughly below the Newport Gateway Visitors Center.

Even today, the past revisits The Point when homeowners dig too deeply.

Bill Hanley, the city’s building inspector and director, recalls when a homeowner on Bridge Street tried to add a small addition to the property about eight years ago. “They ended up having to go 14 feet deep,” to find solid ground to set the foundation, he said. “They were pulling up chunks of old dock, pilings, things that were buried way under the ground; old piers and pilings and rotted wood.”

The entire Point neighborhood is located within the Newport Historic District, a National Historic Landmark District. The designation was made in 1968, the same year the Newport Restoration Foundation was established. The nonprofit preservation organization has since purchased and restored 83 homes in the city, many of them in The Point.

The compact lots and dense development of the neighborhood give it a consistent look. Many of the homes were relocated to the area after America’s Cup Avenue and Market Square were constructed in the 1960s, according to the foundation.

Houses that were moved to the area were often placed on higher foundations, at least several feet above the sidewalk. This typically wasn’t done to prevent water intrusion, but instead to provide more head room in basements, according to historians.

On houses in their original locations, the wooden-plank clapboards and shingles on many of the houses begin just inches from the ground.

What makes a consistent 18th- and 19th-century canopy, and contributes to the historical tourism of Newport, spells problems during storms.

Nowhere is this more apparent than 74 Bridge Street.

Owned by the NRF since 2014, the house was built about 1728 and originally owned by Christopher Townsend, the father of the noted Newport cabinetmaker John Townsend, according to a history of the property.

It sits at the lowest level of The Point, just two blocks from Newport Harbor – and 4 feet above sea level.

Without two sump pumps operating continuously in its basement, it would hold 9 inches of water on a daily basis, according to NRF.

It wasn’t always so. The sea level has climbed 11 inches in Newport over the past 100 years, according to the property history.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded the basement to the first-floor framing and put 7 inches of water into a kitchen addition that had been added in the 1980s.

What can be done to safeguard it?

Raising the house to current FEMA and state building codes would mean elevating it by 7 feet, according to the Newport Restoration Foundation.

This wouldn’t just affect the appearance of the house, but of the entire street and surrounding district.

Intermediate steps have been taken to handle daily flooding. They include the installation of sump pumps in the kitchen and basement, and elevation of its boiler and electrical wiring to the first-floor framing. Lighting fixtures in the basement have protective covers.

What will happen to safeguard the house from the future impact of storms and sea-level rise is uncertain. In preparation for the Keeping History Above Water conference last year, the foundation held a charrette over two days, taking suggestions and ideas from 45 people, according to Shantia Anderheggen, foundation director of preservation.

“It’s elevating. It’s floating. It’s doing nothing,” she said of options discussed.

The Rhode Island School of Design interior architecture program is now conducting a case study on the house and four nearby structures, Anderheggen said.

For homeowners, the costs of raising a house to a height above the flood elevation can be prohibitive, never mind whether it is permissible under Newport’s historic-district requirements.

Anderheggen said that beyond a few individual homeowners, the problem of flooding and the neighborhood character is such that people have recognized that this is not a problem individual homeowners can solve on their own.

“It’s exceedingly expensive,” she said, of raising a house. “We can’t expect that property owners can deal with this on their own.”

She feels the pursuit of design standards that address sea-level rise is, in some ways, premature.

“I think we have to recognize [typical] property owners absolutely cannot afford to do this. And don’t forget these are all now in a flood plain, where insurance rates are going to be skyrocketing,” she said.

From a financial standpoint, if not historical value, the Point neighborhood is worth saving. Just by tax base, an argument can be made that the city has a vested interest in maintaining its value.

Although The Point fell into a decline from the 1960s to the 1980s, when the NRF started buying the houses, it has since surged and is now among the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city, according to property records.

Even with its flooding issues, 74 Bridge Street is valued at $646,900, according to property records.

All told, the foundation owns 28 properties in the Greater Point neighborhood.

“Even our houses, we have millions of dollars of real estate down there,” noted Anderheggen.

Beyond the tax dollars collected from homeowners, the neighborhood is among the must-sees for visitors who descend on Newport for its historical tourism.

Although the Newport mansions remain the top draw for the city, the Colonial neighborhoods are also being showcased to tourists.

NO RETREAT

Some neighborhood homeowners have opted to protect their house systems by elevating furnaces, boilers and electrical systems to the first floors. Hanley’s office can recommend this when a renovation is permitted, but he can’t require it unless the property owner is pursuing a substantial renovation.

“That will buy them time anyway,” said Hanley, of moving up systems out of the basement.

In his office, he comes across property owners who are fairly inventive in trying to keep their homes dry. He has had to reject a few requests. Someone wanted to dig around the foundation, and attach a heavy rubber membrane to the concrete, then secure it so it wouldn’t take on water in a flood, he recalled. He had to explain to the property owner that concrete floats, Hanley said.

“I can’t let you do that,” he told him. “What you’ve just done is make a boat. That’s going to float up in the air and go down the street.”

In new construction, the homeowners have the opportunity to skip the basement and design for flooding. A house on 3rd Street constructed in the 1990s has an elevated front stoop and entrance, which indicates its first level of living space is above the flood plain. The siding on the house extends almost to the ground, a requirement of the Historic District Commission intended to make it seamlessly blend into the neighborhood.

Across the street, the clapboard-sided house occupied by Ilse Buchert Nesbitt and her family looks much as it did in 1835.

Nesbitt, a woodblock print artist, owns The Third & Elm Press print shop, which operates from a ground-level space on the corner of the house. Before she and her husband bought the structure, in 1965, the business space was occupied by a penny-candy store, and before that, a shoemaker and barber.

She guesses the lower level of the house, occupied now by the business, was created at some point before the 1938 hurricane.

“Once you experience that [type of storm], you don’t lower the floor,” she said.

For the more than 50 years that Nesbitt has owned the property, the printing-press business has escaped flooding, although sometimes just barely.

Nesbitt recalled placing stacks of sandbags outside her shop in 2012 for Hurricane Sandy. In another, more recent storm, she watched from the business doorway, as water poured into the basement windows of many of her neighbors on 3rd Street, a few hundred feet closer to the harbor.

Under the URI sea-level-rise scenarios, the shop, along with all of the neighborhood up to Willow and 3rd streets, could be flooded with up to 5 feet of water at high tides, by 2100.

The same scenario will take place in a 100-year coastal storm, comparable to Hurricane Carol, if combined with just 2 feet of sea-level rise by 2050, or with 1 foot of sea-level rise by 2035, if it hits at an astrological high tide.

The scenarios make it seem that almost half of The Point could be lost to inundation.

But what action to take?

Property owners who want to improve their historic structures face a dilemma, Barker said.

Under the state building code, historic buildings in flood zones have an exemption on the design of improvements through grandfathering. But if the architectural or historical integrity is altered, the property owner could lose that exemption. Specifically, if an owner spends more than half of the value of the building on an improvement, within one year, they would have to bring the entire structure into compliance with current flood-plain requirements – an elevation above the higher high water line.

Yet, if they don’t alter the structure’s integrity, they may lose the property entirely, says Fugate.

The options, he said, amount to fortifying an area around the neighborhood, such as a sea wall, elevating the entire neighborhood, or raising individual properties. All are expensive. Relocating houses entirely is another possibility, provided the city has suitable sites.

“You either try to adjust and deal with what’s going on at the site itself, or you relocate,” Fugate said.

But moving the houses out of harm’s way isn’t a solution to many stakeholders.

The Point homes are so close to the water, along with much of the historical assets of Newport, because the city was founded on maritime industries.

“Ideally, we would hope not to lose any [houses],” Barker said. “It is tough. These are such distinct neighborhoods, and the character of the neighborhoods is different. The Point is different from The Hill,” she said, referring to the broader sweep of Colonial homes located above Newport’s downtown.

Anderheggen said “retreating,” the term for relocating a structure, would be the least-favorable option for The Point.

“If we’re retreating, the neighborhood doesn’t exist anymore, does it? I don’t think anybody wants to imagine that NRF or any other property owner would retreat,” she said.

Part of the reason why the foundation initiated the Keeping History Above Water conference was to start the discussion among all the stakeholders, including the city, the state and individual owners, about what positive steps can be taken to protect the neighborhood, she said.

Is the encroachment of the sea inevitable?

“I don’t think we’re even near to answering that question,” she said. “We’re in our infancy of understanding what the problem is, and how each constituency – homeowners, neighborhoods, state, city – what kind of role each of these constituencies play in helping to solve the problem.”

For Fugate, the solutions offered as potential salves – the placement of flood vents, installation of rain gardens, even higher and anchored foundations – may prove to be futile.

“The volume of water overwhelms everything over there,” he said of The Point. “They’re already seeing water infiltrate into that area. The forces that are in the ocean, they’re pretty difficult to battle.”

Over the last 90 years, from 1929 to 2017, Newport has had roughly 10 inches measured of sea-level rise, Fugate said.

“Right now, we’re looking at 10 feet, in the same time period,” he said. “If you have kids today that are young kids, they’re going to see that in their lifetime.” •