Rhode Island audiences have many choices when it comes to small professional theaters: There are at least 10 scattered across the state, from Providence and Pawtucket, to Warren and Newport, to East Greenwich and Matunuck.

But not all are going strong. The Odeum Theater in East Greenwich, for example, shut its doors early this spring because it could not afford to pay the $200,000 it would have cost to install sprinklers to bring the building into compliance with the state fire code.

Though the 410-seat theater is slated to open again once the fire code issue is settled, Frank Prosnitz, president of the theater’s board of directors (and a former PBN editor), said the theater has had other financial struggles.

The Odeum couldn’t attract a consistent audience willing to pay the $10 to $25 per ticket it charged for most shows, and it didn’t qualify for some grants that could have helped because it’s located in an affluent community, Prosnitz said.

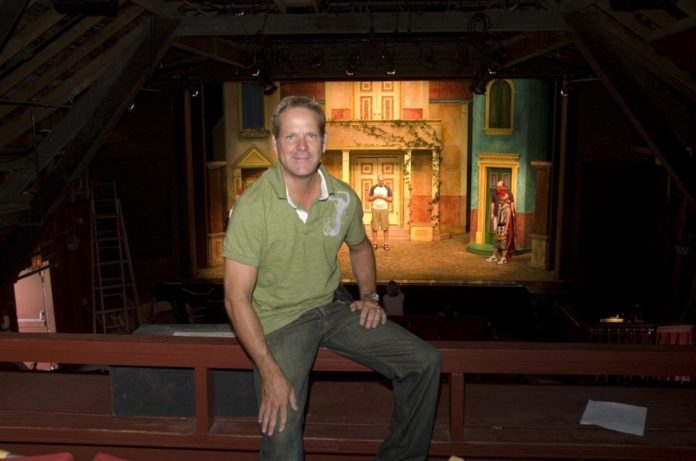

The Theatre By The Sea in Matunuck, meanwhile, reopened last week after a four-year hiatus and is doing well. Its first show, “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” which opened Aug. 10, and will end no later than Sept. 2, already has generated $100,000 in ticket sales, 60 percent of the total available tickets.

The previous owners closed the theater because they wanted to retire, said Bill Hanney, who purchased the 500-seat theater and adjacent restaurant two months ago.

“They retired at 93-percent capacity,” said Hanney, who is also president/CEO and founder of Entertainment Cinemas, which owns and operates nine movie theaters in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Connecticut. “[Seats] were almost full every night for the entire summer.”

And Hanney expects that the 93-percent capacity will continue because the theater is such “a Rhode Island institution” and because he and his partners, Amiee Turner and Joel Kipper, are dedicated to bringing the best performers and productions they can find, he said.

As Hanney sees it, the audience is there. Yet even so, he has decided to turn the longtime for-profit theater into a nonprofit in an effort to ensure its long-term survival.

“I want people to feel a part of the theater,” he added. “If you’re a nonprofit theater, it’s not just about buying tickets … [people can] make donations for whatever amounts and feel like [they are] keeping the theater alive.”

Other long-term benefits to nonprofit status, he said, include the ability to keep ticket prices below market value, explore educational programming and make structural improvements to the 70-plus-year-old building, which is a barn that was converted into a theater.

Bob Colonna, an actor/director and adjunct professor of theater at Rhode Island College who acted at the Trinity Repertory Company for 20 years and operated a small theater, the Rhode Island Shakespeare Theater, from 1971 to 1990, said being a nonprofit is almost crucial “if you want to stick around.”

“I think that the organizations that hang on and succeed and last, have to operate very shrewdly on all fronts,” Colonna said. “And they have to attract people to the board that know how to raise money. It’s a heck of a struggle.”

Colonna recalls making a salary of about $100 per week during the last two years his theater operated. He said its decline had to do with the “me generation” of the late 1980s and early 1990s not wanting to donate funds, but also with a lack of fund-raising skills among the staff and board members.

“We ran out of money,” he said. “We lost our support.”

But losing support isn’t a worry for all of Rhode Island’s small theaters. Some are doing very well, such as 2nd Story Theater in Warren, which earns 72 percent of its income from ticket sales, half of which involve consistent subscribers.

“I run this theater as a nonprofit with a for-profit mindset,” said Ed Shea, artistic director and founder of the 140-seat theater, which he re-established six years ago. “We don’t want to be overly dependent on grants.”

On that front, there are many reasons for 2nd Story Theater’s success.

One is keeping the plays to less than two hours at all costs. Shea said he made that decision because there are so many demands on people’s time these days, and he wants to make sure each moment they spend in the theater is as valuable and concise an experience as possible.

The second is keeping the price at a solid $25 per show or $20 per show for subscribers. It has incrementally increased since the beginning, when standard tickets cost $10 and Shea charged only $5 on Thursdays, just to get a large crowd through the doors, which in turn helped build an audience for the theater.

Another successful decision was the nonprofit’s purchase of the building in 2003, Shea said, because “it has really helped to establish the view of us as a formidable, permanent institution.”

In addition, he said, it has encouraged more consistent donations because people like to know exactly where their money is going. By owning the building, Shea can tell people the money is going to the sprinkler system or to fixing electrical problems or installing new windows.

“In that way, they are investing in the building,” he said. “They are investing in what is important to them.”

Shea also believes in the power of organic advertising. He asks people at the end of each show to tell four friends about the experience they had, and he said the results have been notable.

A typical production costs about $18,000 at 2nd Story Theater, and that doesn’t include administration costs, electricity, heating or printing of promotional materials.

At the Odeum Theater productions, including theatrical and musical performances, the cost per show ranges from $1,500 to $10,000. But even with more seats and a volunteer administrative staff and board, the theater had a tough time being profitable enough to pay for upgrades such as the fire sprinklers.

And though the theater will reopen, Prosnitz said, a lot of that will depend on “the matter of regaining an audience and the energy level of our volunteers.”

“None of us get a dime out of it,” he said. “All we got is the satisfaction of running a theater.” •