So far, the 10 electric vehicle charging stations tucked away in the corner of the 200-space parking lot at Hexagon Manufacturing Intelligence Inc. haven’t gotten much use from the company’s employees since they were installed a year ago.

Still, Steven Ilmrud, Hexagon vice president of operations at the North Kingstown factory, doesn’t consider them a waste of money.

The company, which fabricates air bearings in the Quonset Business Park, ended up getting $80,000 worth of rebates through National Grid (now Rhode Island Energy) for installing the stations, so it cost Hexagon $30,000 in the end.

For Hexagon, the charging stations are symbolic, too, a nod to the company’s much larger sustainability plans that include the goal of generating enough energy from renewable sources – or purchasing credits – to offset the emissions it produces at each of its two dozen factories worldwide by the end of the decade.

“Being green and socially conscious is a good business decision,” Ilmrud said. “It’s something customers are looking for and expecting out of their supply chain and their vendors.”

Other local businesses might soon have little choice but to follow suit as state mandates around emissions reductions prompt major changes to the way they run machinery, heat buildings or transport goods.

The state’s Act on Climate law, passed in 2021, calls for incrementally cutting Rhode Island’s greenhouse gas emissions over the next 27 years, with the goal of hitting net zero by 2050. Though praised by lawmakers and environmental advocates as a landmark commitment to climate resiliency and economic development, the details – such as who needs to do what, how and with what money – are still being developed.

Meanwhile, preliminary modeling suggests the state might miss its upcoming target for 2030 – reducing emissions by 45% compared with the 1990 baseline.

And business leaders are anxiously waiting for what they believe might be an onerous – and expensive – set of changes to their operations.

“There is nothing in [the law] telling us how we are going to do this,” said David M. Chenevert, executive director of the Rhode Island Manufacturers Association. “We aren’t against what it stands for. But they have to come up with a way to cover those costs.”

Take the Cumberland machine shop, Swissline Precision LLC, which Chenevert used to own. It’s a 36,000-square-foot facility with 70 electricity-devouring computerized numerical control machines.

Chenevert looked into buying solar panels, but he determined they weren’t a good fit. And with surging power costs and snarled supply chains plaguing operations, Chenevert couldn’t fathom taking on the cost – and headache – of a project such as converting to electric heat pumps.

Not that anyone has asked him. Chenevert says no one from the R.I. Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council, a consortium of state agencies known as EC4 charged with laying out a plan for reaching the state emissions targets, has reached out to the manufacturing association.

“We’re one of the largest sectors in Rhode Island,” Chenevert said. “We employ a ton of people, and we are a huge consumer of electricity. But I’ve not seen any information about how this affects us.”

[caption id="attachment_434015" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

READY TO TALK: Terrence Gray, director of the R.I. Department of Environmental Management and chairman of the R.I. Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council, acknowledges that officials need to better communicate with the business community about what's ahead on carbon emissions restrictions.

PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

‘A HUNDRED HOOPS’

Terrence Gray, chairman of the EC4 and director of the R.I. Department of Environmental Management, acknowledges that some in the business community such as Chenevert are frustrated.

“We know we need to have better dialogue with the business community,” Gray said. “Not because they were complaining to us, but because their voices have not been reflected in the comments and participation.”

The council has spent the last year gathering input through more than two dozen public workshops and 400 written comments, analyzing spreadsheets of carbon emissions data and creating scenarios of how different actions – such as converting to highly efficient electric heat pumps – could decrease emissions. The result is a 114-page plan published in December that is intended to act as a baseline, updating 2016 data and defining in broad terms the main areas of focus for the Act on Climate.

“This wasn’t meant to be a giant directional document,” Gray said. “If we want to make this happen, we need to have good data, and a good understanding of where we’re at now.”

That baseline understanding is also critical to determining the best ways to spend the millions of dollars of federal funds being funneled into state coffers from COVID-19 relief aid and the Inflation Reduction and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs acts.

The $100 million in federal funds headed to the R.I. Office of Energy Resources marks the largest tranche in agency history, says Christopher Kearns, interim energy commissioner.

Nearly two-thirds of that funding is reserved for energy efficiency rebates for homeowners, but OER will also oversee programs for businesses, such as a $25 million heat pump incentive program included in the state’s fiscal 2023 budget. Gov. Daniel J. McKee proposed another $5 million in his fiscal 2024 budget to help small businesses pay for energy efficiency improvements.

How these programs might work is still being ironed out. But Kearns was confident the funds will help make “significant” progress in key emissions areas such as residential and commercial heating and transportation, which accounted for 30% and 40%, respectively, of state greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available.

Electricity is the other big contributor to gas emissions, responsible for just under 20% of state emissions.

Some businesses have balked at the prospect of replacing furnaces with energy efficient electric heat pumps.

Joseph Andrade, president of home and commercial services for Gem Plumbing & Heating Services LLC, didn’t think the state’s $25 million heat pump incentive program would go far, given the $300,000 heat pump projects he’s completed for some Rhode Island firms.

“Especially not if they make you go through a hundred hoops to get it,” he said.

Indeed, understanding where to go for help (federal or state government or the utility company itself?) or how the finances work (grants, rebates, tax credits?) is enough to confuse many business people. Small-business owners often don’t have the time or staff to figure it out.

“Is the money out there? Yes. Is it easy and simple to get? Right now, it’s not,” said Harry Oakley, director of energy and sustainability at Ocean State Job Lot Inc. and chairman of the R.I. Energy Efficiency and Resource Management Council, which is responsible for overseeing Rhode Island Energy’s energy efficiency program planning and budgeting.

Oakley has expertise in helping his company and ratepayers across the state piece together the puzzle. There’s a lot of confusion, and not a lot of coordination right now, he acknowledges. But he’s optimistic.

“We’re starting to put money in the right places,” he said, referring to the $4.5 million McKee has proposed for EC4 in his fiscal 2024 budget, which would be the first dedicated funding for the council.

[caption id="attachment_434014" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PANEL DISCUSSION: Harry Oakley, director of energy and sustainability at Ocean State Job Lot Inc., stands among solar panels on the roof of the company’s Johnston store. In the confusion around net-zero goals, Oakley is hoping Ocean State Job Lot can lead the way for other businesses.

PBN PHOTO/ELIZABETH GRAHAM[/caption]

LEADING THE WAY

Oakley also thinks Job Lot can be an example for other businesses on sustainability.

The North Kingstown discount retailer in 2021 partnered with solar developer Ecogy Energy to put together rooftop solar panels on 10 of its Rhode Island stores. Once finished later this year, the 2.5-megawatt solar portfolio will be the largest rooftop array participating in Rhode Island Energy’s Renewable Energy Growth Program, which offers long-term, fixed-rate tariffs to incentivize green energy projects.

Job Lot doesn’t actually get the energy credits – they go to the solar developer – but makes money for leasing its roof to Ecogy.

The company also gets to count the power from the solar panels toward its net-zero emissions goal. Job Lot plans to publish an action plan later this year outlining how – and when – it will achieve net-zero emissions, tentatively aiming for 2050, according to Oakley.

In 2021, the company achieved net-zero waste, meaning it recycles more waste than it adds to landfills each year.

Like Ilmrud, Oakley sees corporate emissions targets as philosophically and financially beneficial.

“We feel we have a responsibility to be providing a positive impact to the communities we serve,” Oakley said. “It enhances the idea of a brand that customers can trust.”

Leading by example is also the state’s approach.

In February, the R.I. Department of Transportation became the first state agency to fully convert to LED lightbulbs, including changing out more than 9,000 streetlights that will save an estimated $1 million in annual electricity costs and cut 55,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions, according to the state.

Meanwhile, the R.I. Public Transit Authority is gradually replacing diesel-powered buses with electric vehicles. The quasi-public agency will be launching its first, fully electric fleet this spring along the R-Line between Providence and Pawtucket. Another $23 million federal grant will pay to electrify the 25 buses serving Aquidneck Island by the summer of 2024.

At $1 million a bus, it’s not cheap. Especially with 75% of the 200-bus fleet still running on diesel, according to Scott Avedisian, RIPTA CEO.

“These are very expensive, and it’s not easy to just get rid of a bus and buy a new one,” Avedisian said. “We’re applying for all sorts of grants and moving forward cautiously based on the funding we have available.”

RIPTA hasn’t set a goal year for reaching net-zero emissions, and it might end up incorporating other types of technology such as hydrogen fuel-cell-powered buses, according to Sarah Ingle, RIPTA’s director of long-range planning.

RIPTA buses only account for a tenth of a percent of state emissions, which is why the transit agency is also focused on wooing people out of their cars and onto buses to make a bigger dent in state greenhouse gas emissions.

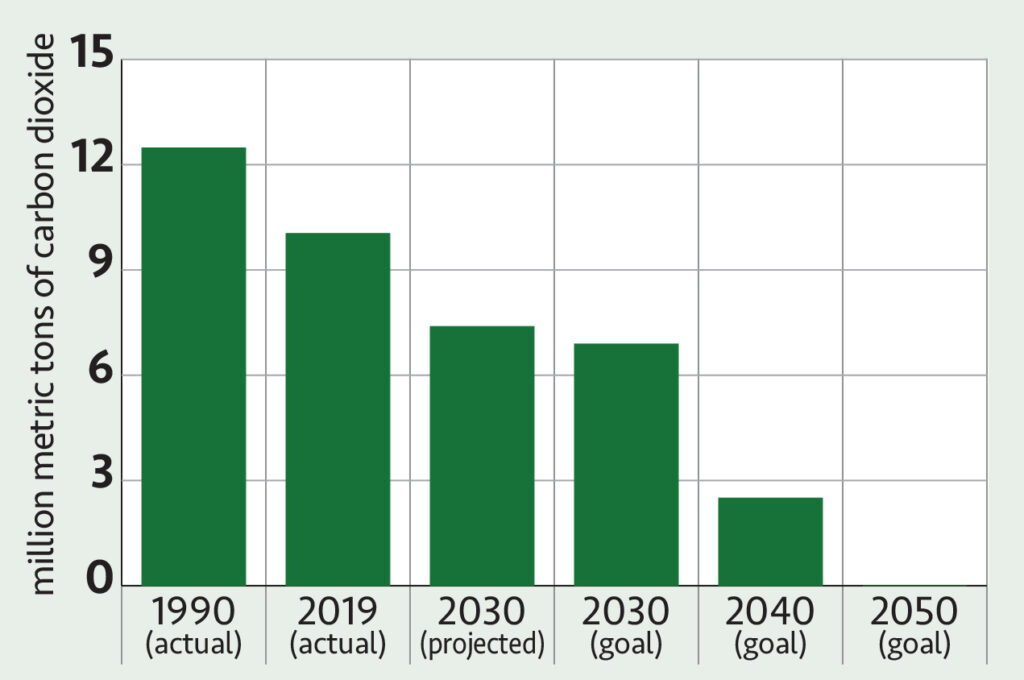

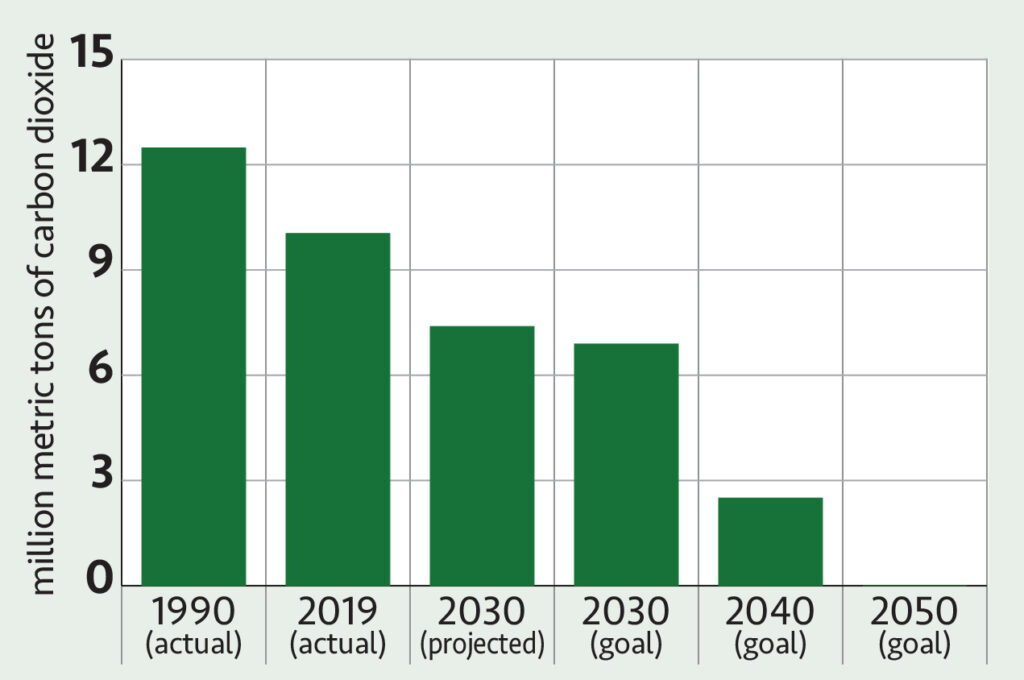

[caption id="attachment_434017" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

TARGETS FOR R.I.’S NET EMISSIONS Rhode Island’s Act on Climate sets goals to reduce greenhouse gases in 2030, 2040 and 2050. However, projections indicate that the state might miss the target for 2030. The goal for that year is 6.89 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. Current estimates are that emission levels will be 7.39 million metric tons.

/ Source: R.I. Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council[/caption]

INCENTIVES VS. PENALTIES

But reaching net zero will also require the private sector to get on board – with electric vehicles, solar panels, heat pumps and even more-efficient thermal insulation.

Right now, most state policies and programs are incentive-based. At some point, there might have to be penalties, not just rewards, Gray says.

“We have aggressive targets, and we know there will be some folks that lag behind that need a little push,” Gray said. “That’s the model in any regulatory setting.”

David Caldwell, vice president of North Kingstown-based homebuilder Caldwell & Johnson Inc. and past president of the Rhode Island Builders Association, disagrees.

“Consumers don’t react positively to mandates,” Johnson said. “They do better with incentives and education.”

Before imposing penalties on consumers and companies, Johnson urges the state to turn the microscope on itself. According to Johnson, the state has not adhered to a 2009 law requiring large public building and renovation projects to be built to high-performance green standards.

Caldwell doesn’t have much confidence the Act on Climate law won’t fall by the wayside the way the 2009 Green Buildings Act has.

“We support aspirational goals, but you have to put the details behind it,” Caldwell said. “Act on Climate seems largely aspirational right now.”

One potential motivator: starting in 2026, the attorney general or any resident or company can sue the state for failing to meet its incremental planning goals or emissions benchmarks.

Ahead of the looming litigation deadline, R.I. Attorney General Peter F. Neronha is leveraging a state settlement with Rhode Island Energy to help ensure the state is on track to meet its incremental benchmarks. As part of the settlement reached when parent company PPL Corp. bought utility operations in 2022, the company agreed to monetary and reporting commitments related to the Act on Climate law.

Based on this agreement, Neronha in February sought to challenge the company’s gas infrastructure improvement plan, arguing in filings to the R.I. Public Utilities Commission that the company “fails to adequately account for Act on Climate mandates to reduce and eliminate greenhouse gas emissions.”

Rhode Island Energy is also proposing a $529 million, 20-year plan to modernize the electrical grid, which includes upgrades to accommodate the two-way flow of power from home battery storage systems, rooftop solar panels and other “distributed energy resources.”

Carrie Gill, head of the electric regulatory strategy for Rhode Island Energy, says the company is “absolutely committed” to achieving state emissions mandates. PPL has touted its expertise and recognition received for grid modernization in Pennsylvania.

However, PPL’s lack of offshore wind experience was a concern for some environmental advocates at the time of the sale, especially because the utility operator is being tasked with overseeing and awarding a bid to develop another 1,000 megawatts of offshore wind for the state. The power generated by that project, on top of the 400 megawatts coming from the Revolution Wind project planned off Block Island, is going to move the state “a long way” toward its net-zero goals, Gray says.

But offshore wind projects have faced delays, tied up in lengthy federal reviews and post-pandemic supply chain woes.

TAKING AIM

To hit the state’s 2030 target, the EC4 report recommended stricter emissions standards for new cars sold in the state and an “aspirational target” that 15% of buildings in Rhode Island switch to electric, energy efficient heat by 2030.

As of late February, no legislation has been introduced based on these recommendations.

“The pace at which we are going right now is insufficient to meet our goals, but that doesn’t mean we can’t,” said Stephen Porder, Brown University’s associate provost for sustainability and an ecology and evolutionary biology professor. “This is not a scientific challenge. It’s a political will challenge.”

Gray said he was confident the state would hit the 2030 benchmark, noting that preliminary modeling suggesting that the state might fall short was too abstract to put much weight in.

As for hitting net zero?

“I am not here to declare victory or defeat in 2050,” Gray said. “We are treating them as final targets, but that could change over time. It could become more, or less aggressive.”

Ilmrud, meanwhile, was focused on hitting net zero for the company’s 110,000-square-foot North Kingstown factory.

Hexagon is reviewing proposals to install 500 megawatts worth of solar panels, either on the roof or in the parking lot, which could generate enough power to fill half of the Quonset factory’s electricity use. The rest of its emissions will have to be offset through renewable energy credits and battery storage systems, Ilmrud says.

“It’s a challenging goal, but we’ve committed to it as a corporation,” Ilmrud said. “We want to continue acting as a leader.”