NEW YORK – This summer American teenagers should find it a little easier to get a job—if they want one.

The U.S. unemployment rate fell to 4.3 percent in May, the lowest in 16 years, so teens started looking for summer jobs in the best labor market since the tech boom of the early 2000s. The May unemployment rate for 16- to 19-year-olds was 14.3 percent, but teens usually find it harder to find jobs than their more experienced elders. Back in 2009, the teenage jobless rate hit 27 percent.

A CareerBuilder survey of 2,587 employers released last month found that 41 percent were planning to hire seasonal workers for the summer, up from 29 percent last year.

But the unemployment rate measures joblessness only among people who are actively looking for work. And many American teens aren’t.

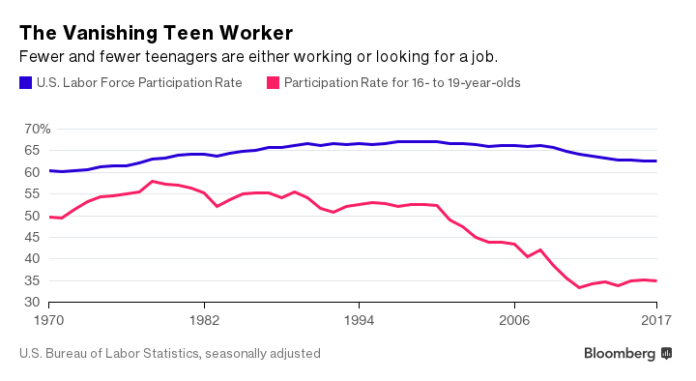

For Baby Boomers and Generation X, the summer job was a rite of passage. Today’s teenagers have other priorities. Teens are likeliest to be working in July, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that’s not seasonally adjusted. In July of last year, 43 percent of 16- to 19-year-olds were either working or looking for a job. That’s 10 points lower than in July 2006. In 1988 and 1989, the July labor force participation rate for teenagers nearly hit 70 percent.

Whether you’re looking at summer jobs or at teen employment year-round, the work trends for teenagers show a clear pattern over the last three decades. When recessions hit, in the early 1990s, early 2000s, and from 2007 to 2009, teen labor participation rates plunge. As the economy recovers, though, teen labor doesn’t bounce back. The BLS expects the teen labor force participation rate to drop below 27 percent in 2024, or 30 points lower than the peak seasonally adjusted rate in 1989.

Why aren’t teens working? Lots of theories have been offered: They’re being crowded out of the workforce by older Americans, now working past 65 at the highest rates in more than 50 years. Immigrants are competing with teens for jobs; a 2012 study found that less educated immigrants affected employment for U.S. native-born teenagers far more than for native-born adults. Parents are pushing kids to volunteer and sign up for extracurricular activities instead of working, to impress college admission counselors. College-bound teens aren’t looking for work because the money doesn’t go as far as it used to. “Teen earnings are low and pay little toward the costs of college,” the BLS noted this year. The federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour. Elite private universities charge tuition of more than $50,000.

Or maybe, as cranky old people have asserted for generations, teenagers are just getting lazy.

A recent BLS analysis offers another theory, backed up by solid data. It appears that millions of teenagers aren’t working because they’re studying instead.

Over the last few decades, education has taken up more and more of teenagers’ time, as school districts lengthen both the school day and the academic year. During the school year, academic loads have gotten heavier. Education is also eating up teenagers’ summers. Teens aren’t going to summer school just because they failed a class and need to catch up. They’re also enrolling in enrichment courses and taking courses for college credit.

In July of last year, more than two in five 16- to 19-year-olds were enrolled in school. That’s four times times as many as were enrolled in 1985, BLS data show.

Students have more to learn in their four years of high school. In 1982, fewer than one in 10 high school graduates had completed at least four years of English classes, three years of math, science, and social science, and two years of a foreign language. By 2009, the most recent data in the U.S. Digest of Education Statistics, the share of grads taking those classes was almost 62 percent.

High school students aren’t just taking more classes. They’re taking tougher ones. What’s happened in math reflects trends in other areas. Calculus is up threefold since the early 1980s, while precalculus is up more than fivefold, and statistics and probability courses are up tenfold. Almost a million students graduated in 2009 having taken an advanced placement (AP) class, up 39 percent from four years earlier.

All this studying has obvious benefits, but a single-minded focus on education has disadvantages, too. A summer job can help teenagers grow up as it expands their experience beyond school and home. Working teens learn how to manage money, deal with bosses, and get along with co-workers of all ages.

A summer job can even save lives. In a study released last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, researchers analyzed the effects of two Chicago programs providing students with part-time jobs along with mentors for the summer. The programs had little apparent effect on the teens’ later employment or education—a big concern in itself—but arrests for violent crime plunged, by 42 percent for one program and 33 percent for the other, an effect felt for at least a year after the programs ended. If teens got nothing else out of the jobs programs, the researchers suggested, they were at least “learning to better avoid or manage conflict.”

Ben Steverman is a reporter for Bloomberg News.