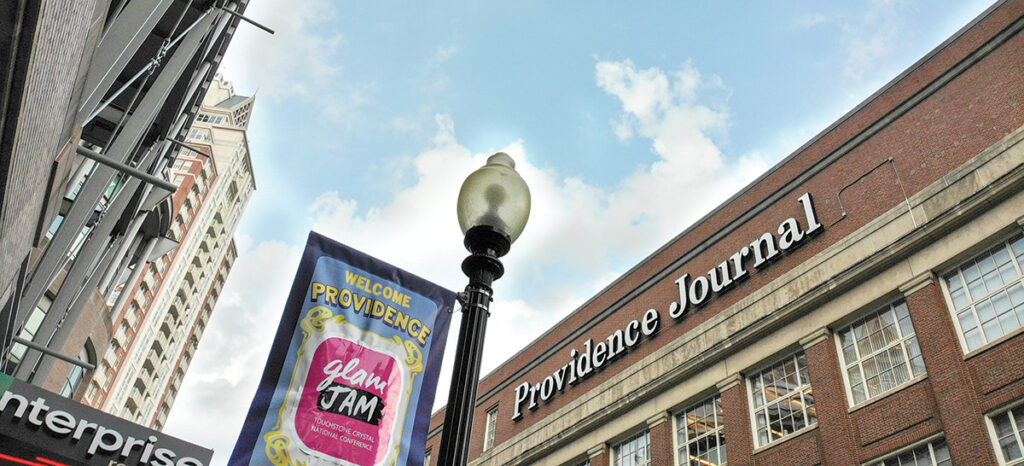

The sprawling four-floor, brick building with arched windows at 75 Fountain St. in downtown Providence still appears to be the quintessential American metropolitan daily newspaper of the 20th Century. In bold letters, the name across the top of the building reads “Providence Journal.”

But we are in the 21st century. Things inside the Journal building – and in the newspaper industry overall – are, to put it politely, a lot different. The newspaper once occupied the entire building. Today, it leases just part of the second floor.

By now, it’s a familiar national story played out locally, in this case in Providence and surrounding communities.

Disruptive technology has led to declining advertising revenue, falling circulation, drops in subscriber numbers and layoffs. The result is consolidation under ownership groups looking for economies of scale and the improved profit margins they are supposed to bring. But the bottom keeps falling out of the industry.

In southeast New England the ownership group of the moment is GateHouse Media Inc., or technically, its parent company, New York-based New Media Investment Group Inc. Listed on the New York Stock Exchange, New Media has grown into one of America’s largest newspaper chains in recent years, and according to The Wall Street Journal, it soon may become even larger as it attempts to swallow Gannett Co., the publisher of USA Today and many other newspapers.

[caption id="attachment_289147" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

SHRINKING PRESENCE: Steady declines in advertising revenue and circulation at The Providence Journal have led to a series of layoffs and increased competition from The Boston Globe. The Journal has been steadily shrinking since GateHouse Media bought it from A.H. Belo in 2014.

/ PBN PHOTO/PAM BHATIA[/caption]

HOW IT STARTED

New Media bought The Providence Journal in 2014 from Dallas-based media company A. H. Belo Corp. for $46 million, although New Media’s corporate structure makes any transaction it undertakes far from simple to understand.

For example, New Media’s largest shareholders are Blackrock Inc. and Vanguard Group Inc., two of the largest providers of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

Other investment management firms also own a piece of New Media. Fortress Investment Group LLC – a global investment manager for institutional and private investors – owns a fraction of the company, but a Fortress affiliate manages and advises New Media. In fact, Fortress created New Media as an investment vehicle coming out of GateHouse’s $1.2 billion bankruptcy in 2013. Fortress, meanwhile, was acquired in 2017 by Japanese multinational conglomerate SoftBank Group Corp. for $3.3 billion in cash.

So, the question remains: Will this network of corporate owners, stretching from New York to Tokyo, find a way to reinvent the Journal for success in New England in the new millennium? Or will they simply feast off the cash it spins off before leaving it to the next group of Wall Street bargain hunters?

Dan Kennedy, an associate professor of journalism at Northeastern University in Boston who has followed developments at GateHouse, said the company seems to be in it for the long haul.

“GateHouse’s cuts have hurt their journalism and harmed their ability to meet the informational needs of the community they serve,” Kennedy said.

“At the same time, I do think they’re in it for the long term, and I think they’re trying to find ways to solve the terrible problem that the newspaper business faces in paying for its journalism,” he added.

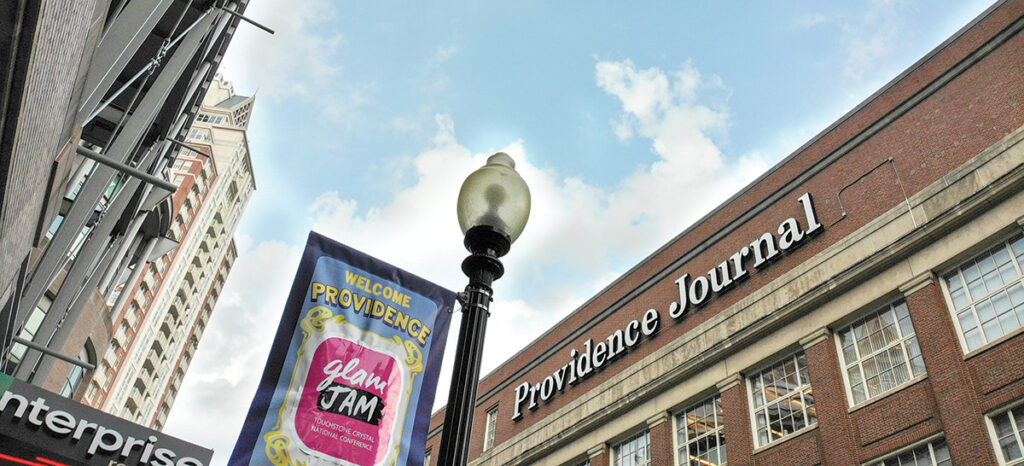

[caption id="attachment_289148" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

FIT TO PRINT: Creative Circle Media Solutions founder and President Bill Ostendorf says print publications are still where the profits are for newspapers. A former editor at The Providence Journal, he says the most stable newspapers are those not owned by investment banks.

/ PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

Bill Ostendorf, a former Journal editor who left the paper nearly 20 years ago and started a media consulting business, Creative Circle Media Solutions in East Providence, is less optimistic about GateHouse’s intentions.

“GateHouse is not interested in reinventing the Journal or making it better. Their only interest is preserving their investment returns,” Ostendorf said. “I know plenty of family-owned newspapers. Most are doing fine – if they’re owned by people who care about the community.”

BAD BLOOD

For Michael Lederman of Little Compton, his support of the Journal ended last November when the self-described loyal and longtime Journal reader canceled his subscription. It happened because of a dispute over the terms of his subscription.

‘Today I canceled my subscription.’

Michael Lederman, Former subscriber to The Providence Journal from Little Compton

His plight may sound trivial, but it’s indicative of the dire challenges that Rhode Island’s flagship news outlet and many others around the country face under ownership by corporate chains or private-equity investors under pressure to maximize profit in an era of rapidly evolving media platforms.

“Today I canceled my subscription,” Lederman wrote in a letter to the Journal. “I did so after learning that you had shortened my subscription period by periodically including with my daily paper certain special inserts that I had neither requested nor had any interest in receiving.

“In other words,” he continued, “The paper has me pay for a subscription lasting a certain period of time and then unilaterally shortens that period because the paper chose to send me some special inserts. Sounds good for the paper, not so good for its subscribers.”

The insert booklets have included cooking recipes, games and puzzles, a Boston Red Sox season preview and a retrospective of Providence in photos.

Lederman wasn’t the only one complaining about it. In 2017, GateHouse agreed to settle a class-action lawsuit in Massachusetts brought by subscribers to its newspapers there over the company’s practice of charging for “premium” inserts and supplemental publications that subscribers hadn’t asked for.

However, according to the plaintiffs, instead of billing them for the inserts, GateHouse simply shortened their subscriptions to cover the costs of the supplements, so subscribers who bought a one-year subscription might end up getting only 30 weeks of a paper. The plaintiffs claimed GateHouse failed to properly disclose that.

GateHouse, meanwhile, disputed the allegations and was not required to admit any liability under the settlement.

Representatives for GateHouse and the Journal did not respond to requests by Providence Business News for comment on the paper’s current subscription practices and other matters.

Kennedy said he doesn’t like the use of special sections and inserts to enhance revenue.

“If I want the paper, I want the paper. Raise the price and maybe I’ll pay for it. And if I don’t want the paper, I won’t pay. This gamesmanship with crappy supplements is not anything that appeals to me,” Kennedy said. “So just charge [for] them.”

WHERE IS THE BOTTOM?

One way the industry has responded is by raising subscription and newsstand prices to boost circulation revenue.

For instance, in 2015 the Journal increased its single-copy newsstand prices from $1 to $2 for the Monday through Saturday editions, while the price for its Sunday edition remained at $3.50. Today, the Journal costs $3 Monday through Saturday and $4 on Sunday.

Industrywide, however, that strategy has not been enough to offset the loss of its traditionally strongest source of revenue, advertising.

In 2000, for example, advertising revenue among U.S. newspapers totaled nearly $46.3 billion, while circulation revenue totaled nearly $10.5 billion, according to the Pew Research Center.

By last year, advertising revenue had fallen to an estimated $14.3 billion, while revenue from circulation grew to an estimated $11 billion.

‘GateHouse’s cuts have hurt their journalism and harmed their ability to meet the informational needs of the community they serve.’

Dan Kennedy, Northeastern University associate professor of journalism

Adjusting for inflation from 2000 to 2018, however, that $10.5 billion of circulation revenue in 2000 would have been worth $15.3 billion last year. The adjusted advertising picture is even more stark. Just to generate the same inflation-adjusted advertising revenue in 2018 from $46.3 billion in 2000, newspapers would have had to generate $67.5 billion in ad revenue.

In the past, print advertising and classified ads accounted for 80% of revenue for newspapers, Kennedy said, but much of that ad money now goes to online platforms such as Craigslist, Google and Facebook. And, he said, digital ads on newspapers’ websites haven’t come close to making up for the losses.

New Media reported a $9.4 million loss in the first quarter of 2019, impacted by the company’s ongoing acquisition costs. The loss came despite a nearly 14% increase in first-quarter revenue, compared with the first quarter of last year. That revenue increase, however, was driven by strong performance from GateHouse Live, the company’s events business, and UpCurve, the company’s marketing business, as well as the increased revenue coming from newly acquired properties. One additional growing source of revenue is commercial printing, something that many newspaper companies have been adding for this reason (at the same time that their client newspapers have shed their printing presses to cut costs). New Media saw this revenue stream grow 19.4% year over year in the first quarter.

Despite the overall loss, however, New Media was able to pay out $23.2 million in dividends to investors.

Other services, such as GateHouse Live and UpCurve “make a great deal of sense,” Kennedy said. “You want to try to generate revenue that can support the newspapers that also have some tie to the newspapers. The [publication] is kind of the community hub, and the other businesses exist as spokes to that.”

But it is unclear if the gains being made will offset the drops in circulation at the Journal. In the first quarter of this year, the paper’s print circulation had dropped to an average of 51,248 on Sundays, 40.4% less than an average of 85,984 in the first quarter of 2015, based on data supplied by the Alliance for Audited Media (the company reports Sunday circulation including print, digital replica and digital nonreplica as 56,272, but it is not clear how many of this number are duplicates of the print subscriber figure). Meanwhile, print circulation for Monday through Friday dropped to an average of 39,536, 40.1% less than the average of 65,962 four years earlier.

And what’s been happening at the Journal has been happening more or less across the industry. Total circulation for U.S. newspapers on weekdays fell 29% during the four-year period from 2014 to 2018. Total Sunday circulation fell 28%, according to statistics from Pew.

As a result, layoffs at newspapers have become common, including at the Journal. The most recent local round came in May. Across the nation, about one-third of large U.S. newspapers suffered layoffs during the 16-month period from January 2017 through April 2018, according to a Pew analysis.

Nationwide, New Media owns 156 daily newspapers and 328 weekly newspapers, according to the company’s website. That includes two dailies in Rhode Island – the Journal, The Newport Daily News and The Independent in South Kingstown. In Massachusetts, the company owns 119 papers, mostly weeklies, including nine papers in nearby Bristol County.

In May, however, GateHouse announced to its New England division staff that it would merge 50 of its Massachusetts papers into 18 new publications. In Bristol County, that includes lumping the Raynham Call, the Easton Journal, and the Mansfield News in with the Bridgewater Independent to create one new paper called the Journal-News Independent, according to an internal GateHouse memo.

[caption id="attachment_289151" align="aligncenter" width="696"]

DECLINING NUMBERS The Providence Journal has been shrinking since GateHouse Media bought it from A.H. Belo in 2014. Recurring cycles of layoffs and circulation drops have occurred regularly since then. Print-only circulation averages are for the first quarter for Sunday, weekday and Saturday newspapers from 2015 through 2019, continuing an already ongoing trend.

Note: Circulation figures include print figures only, since print and digital numbers may include duplicates.

Source: Alliance

for Audited Media / PBN PHOTO/PAM BHATIA[/caption]

GateHouse executives said individual communities would get the same local news coverage. There was no mention of staff reductions, though they said the consolidation would reduce production expenses.

“Our readers will continue to receive the same in-depth local news coverage of their town plus additional reporting from nearby communities, giving them up-to-date news on what’s happening in their region. Our advertisers will receive increased print market reach, simplified buy execution and enhanced digital opportunities,” reads a company memo.

The memo came from Peter Meyer, the newly named president and publisher of The Providence Journal, who came aboard when the southeastern New England consolidation took place, and Lisa Strattan, the vice president of news in New England for the company. She also serves as the general manager of the company’s southeastern Massachusetts publications.

GateHouse and other newspaper chains “are aiming for certain economies of scale,” Kennedy said. Gatehouse has taken the concept further by moving editing and design duties at many of its newspapers, including the Journal, to one design center in Austin, Texas.

“I really don’t think that corporate chain ownership of newspapers works, because I think that the profit demands really exceed what community newspapers are capable of earning,” Kennedy said.

“I don’t think it is a good model. The problem right now is that it doesn’t look like much of anything is an especially good model,” he added. “The few independent newspapers are struggling as well.”

SEEING AN OPENING

One company’s layoffs can be another’s opportunity. The significant layoffs at the Journal have opened a path for The Boston Globe to come in and start competing in Rhode Island.

David Dahl, the Globe’s deputy managing editor of print and operations, said the Globe plans to open a Providence bureau this month to support its reporting in the Ocean State. The three reporters the Boston-based organization hired in the spring have been working from home and public places.

The Journal layoffs were a factor, Dahl said. “We see an opportunity to provide Globe-level journalism to Greater Providence. … We can tell our stories and find new readers, and that’s exciting.”

Kennedy said that, “If the ‘ProJo’ had another half dozen more reporters, it would have been less attractive for the Globe to try to do this.”

Ostendorf called the Journal “a shell of what it used to be. It used to be one of the best newspapers in the country, and now it’s mediocre.”

He said a mistake made by many newspapers, including the Journal, is not putting enough resources into their newsrooms.

“People who say print is dead don’t have any sense of history or the research to back it up,” he said. “Print is where the profits are. You can’t just shift it to digital. That’s failure mode. Even with most digital [news] companies, 80% of the money comes from print. When was the last time you clicked on a digital ad?”

[caption id="attachment_289150" align="alignright" width="250"]

MORE IS LESS?

The Providence Journal has tried to slow declining circulation by increasing the number of special inserts included in the newspaper. The sections, which subscribers pay for, include cooking recipes, games, puzzles and a retrospective of Providence in photos. Some subscribers have complained the inserts shortened the length of their subscriptions without their knowledge.

/ PBN PHOTO/ANNE EWING[/caption]

Loss of “ad revenue is not the [only] reason newspapers are sliding back,” Ostendorf said. “It’s because they’re dull and boring. [Our firm tries] to keep newspapers from making self-inflicted wounds.

“Newspapers are in trouble because of what they started doing 40 years ago,” he added. “They have to stop cutting the wrong things. Many newspapers are doing quite well and are stable, as long as they’re not owned by investment banks.”

Renowned news media critic and University of Illinois communications professor Robert McChesney, author of books such as “Rich Media, Poor Democracy” and “The Death and Life of American Journalism,” has argued that democratic societies should subsidize news production to keep the public properly informed about government and private-sector power.

“First of all,” McChesney wrote in a 2016 essay, “Journalism is a requirement for a democratic society or a free society; any sort of quality society requires credible, independent, powerful journalism.

“You need a system that will assess people in power and people who want to be in power so that those outside of power know who the players are and what they are doing,” he added. “You need journalism that provides what is called an early-warning system, which will alert you to the problems, so you can nip them in the bud and address them before they get more difficult, or far more expensive, to deal with.”

John Howell, publisher at Beacon Communications, in Warwick, which prints three weeklies – The Warwick Beacon, The Cranston Herald and The Johnston Sun Rise – and some specialty publications, was part of a group consisting of two other local newspaper publishers and a local real estate developer that tried to buy the Journal several years ago from Belo, but GateHouse outbid them.

“We wanted to keep it locally owned,” Howell said about his group. “The feeling was there would be an advantage to that [for Rhode Island’s community] rather than having the Journal be something driven by the stock market.”

Though the Journal is “a shadow of what it was,” Howell said, the editorial staff there does a good job with the resources it’s given. “They have good reporters. They do good stories. They dig in. They investigate. They are working to make it a good paper.”

Scott Blake is a PBN staff writer. Contact him at Blake@PBN.com.