Starbucks customers swinging through the drive-thru on a June morning in Warwick were greeted by something many weren’t expecting: a group of baristas and others holding signs with messages such as “Grind coffee, not workers” and “I want my coffee union made.”

It was an informational picket line ahead of a crucial vote for the 17 employees of the Starbucks Corp. outlet in a busy shopping plaza off Route 2 – a vote on whether they should unionize.

Many drivers beeped horns in support, pumped fists or rolled down their windows to let out a cheer.

Cassie Burke, 23, a Starbucks employee and organizer of the union effort, was among those holding signs. And she wasn’t hiding her frustration.

“With this current generation, there’s a lot of people who do not feel represented through government and law,” she said. “They see this as a way to make change in their community aside from voting every two years.”

The runup to the early June vote was perhaps the most visible example of a new type of union movement rippling across Rhode Island and the rest of the country, one of self-organization that runs counter to traditional labor organizing that has tended to be led by seasoned union officials.

This spark of union activism has been led largely by determined, young rank-and-file workers who are seemingly emboldened in part by changes to workplaces and the economy brought on by COVID-19.

The vote at Starbucks in Warwick was close, 9-8 in favor of unionization. But two ballots have been contested and, as of July 20, the outcome remained under review by the National Labor Relations Board.

Still, the homegrown movement forges ahead, occurring at large companies, small shops and in nascent industries, too. In some cases, it’s putting owners in the position of making a decision of their own: fight unionization or accept it.

In June, when the owners of Providence-based Seven Stars Bakery were notified by employees at its five locations that they intended to unionize, owners Bill and Tracy Daugherty voluntarily decided to recognize the union.

And the Ocean State Cultivation Center in Warwick – which grows cannabis for the state’s licensed dispensaries – signed a labor peace agreement with the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union in 2019.

Other companies with deeper pockets, such as Starbucks and Amazon.com Inc., have launched campaigns to persuade employees to reject unions.

“From the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we are better together as partners, without a union between us, and that conviction has not changed,” Starbucks said in an emailed statement when asked for comment.

TRANSFORMATIVE?

The upswing in unionizing activities is a reversal of fortune for the labor movement, which has suffered from decades of declining membership and waning influence nationwide.

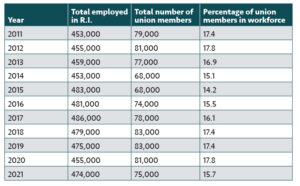

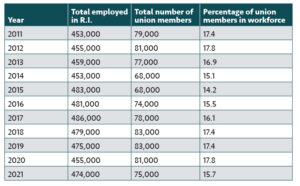

Even in Rhode Island, which remains one of the most unionized U.S. states, total union membership among its workforce dropped from 81,000 in 2020 to 75,000 last year, while the total number of people employed jumped from 455,000 to 474,000, according to data compiled by the New England office of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But now the labor activism that has hit prominent, modern U.S. businesses such as Starbucks, Amazon and Apple Inc. stores has the chance to be a revival on par with the formation of major labor unions in the early 20th century, says Erik Loomis, a labor history professor at the University of Rhode Island and author of “A History of America in Ten Strikes.”

“These companies are the Fords and General Motors and U.S. Steels of our age,” Loomis said. “To organize these places and to bring them under union contracts, where workers had a say in the conditions of their workplace, could be the equivalent of the United Auto Workers, United Steel Workers and other industrial unions.”

There are indicators that the momentum is growing.

The National Labor Relations Board says it has seen a 57% increase in the number of petitions for union representation filed by workers, jumping from 748 in the first six months of fiscal 2021 to 1,174 in the same period of 2022.

Loomis cautions that it’s too early to know whether the movement will have staying power.

“It could be transformative. It could fizzle out,” Loomis said. “But there’s absolutely every reason to believe this is going to grow and grow, and you’ll see more of this. Because when some unionization efforts succeed, it leads to others trying.”

[caption id="attachment_412467" align="alignright" width="300"]

FIGHTING ON: John Foley, a former employee at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick who reached out to employees about forming a union, has filed complaints with the National Labor Relations Board after the company informed Foley not to speak to Jay employees about unionizing.

PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY[/caption]

SELF-STARTERS

The efforts certainly inspired John Foley.

The 35-year-old Providence resident had been on the job as a supply chain and demand planner at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick for less than a year when he learned of the organizing activities at Starbucks and Amazon months ago.

Foley had never been affiliated with a union before, but he says it wasn’t long before he was reaching out to other employees about forming a union to demand better pay for new employees and to address other workplace frustrations.

“The real catalyst was seeing how my fellow co-workers dealt with what we’re dealing with day to day,” Foley said. “I had heard of Starbucks and Amazon unionizing. And if they could do it, we could do it.”

This type of independent initiative has much of the old guard of the union movement taking notice because it isn’t relying on experienced organizers from large, long-established labor groups to do the groundwork.

In the case of Starbucks, it started with a group of workers at a store in Buffalo, N.Y., voting to unionize in January and becoming the first Starbucks outlet represented by the Service Employees International Union-affiliated Workers United. Since then, workers at hundreds of other stores have filed to unionize, and similar actions have happened at places such as Amazon warehouses and Recreational Equipment Inc. – or REI – stores.

“This is self-started in many of these places,” said Scott Duhamel, secretary and treasurer for the Rhode Island Building and Construction Trades Council, a coalition of 16 craftsmen unions.

“No particular union has sought them out,” Duhamel said. “Traditionally, we’d have union representatives do visits, meet people at home or have everybody meet us off-site. This is certainly a new kind of movement.”

In some cases, Duhamel says, these independents seek assistance from well-established labor groups to help defray legal costs, and affiliations are formed that strengthen the overall union movement.

“We feel encouraged,” Duhamel said. “It’s been a long time since we’ve seen stuff like this.”

THE REACTION

Of course, not everybody’s happy about it.

For instance, Starbucks has fought against a union infiltration of its more than 15,000 U.S. stores and its CEO Howard D. Schultz has warned that unionization will prevent the multibillion-dollar company from implementing unilateral changes, including wage increases that were announced last year.

From the perspective of many business owners, union activities mean added costs and wasted time, and an added barrier between managers and their employees, says Timothy C. Cavazza, a management-side labor attorney at the Providence-based Whelan Corrente & Flanders LLP.

“It can be costly when dealing with contract negotiations every year or every three years, or when facing a strike that’s aimed at hitting production or affecting supply chains,” Cavazza said. “It’s the costs in terms of the legal fees and the consulting fees. It’s the management and supervisory time away, pulling people off an assembly line trying to get a product out the door, to engage in 12 hours of contract negotiations and trying to fill holes while workers are out striking.”

At Jay Packaging Group, Foley’s attempt to organize the workforce apparently didn’t go over well.

Foley says the company claimed he made statements indicating that he resigned from the job, but he denies that. Jay Packaging later offered him a severance agreement providing back pay and a small additional sum but refused to bring him back to work, Foley says.

Working with an organizer for Teamsters Local 251, Foley filed complaints with the NLRB accusing the company of unfair business practices when it informed other employees not to speak to him and told him he couldn’t contact colleagues to organize. Foley still hopes to be reinstated.

Jay Packaging did not respond to an email and a phone call seeking comment. But in a letter to Foley’s attorney, the company said it would not agree to bring Foley back, citing his “evident unhappiness” and questioning “why he would even want” to return.

Things have proceeded differently at Seven Stars Bakery.

Dozens of workers at the bakery’s five locations, in Providence, East Providence and Cranston, notified management by letter in mid-June that they were starting the unionization process, saying they were looking for better pay and benefits.

Days later, management had agreed to recognize the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 328 as the workers’ representative.

Co-owner Bill Daugherty declined to comment recently, saying both sides are “in a bit of a quiet period” as Local 328 gets “up to speed” before starting collective bargaining.

Cavazza says his workload has increased due to the recent rise in labor activism. His advice for companies: be proactive before finding themselves in the midst of a unionization campaign.

He also says it’s important for employers to remember “what not to do in these circumstances.” The NLRB states that employers may not discriminate in any way against a worker participating in union activities, such as threatening, interrogating, or spying on pro-union employees, or promising benefits if they drop unionization efforts.

“Try to keep employees happy and don’t give them a reason to seek out that representation,” Cavazza said. “Keep supervisors and managers trained on how to effectively respond when faced with this kind of activity. And just run a good business. Don’t derail everything simply because this activity is going on.”

[caption id="attachment_412470" align="alignright" width="300"]

Rhode Island has historically been one of the most unionized states in the country, but total union membership fluctuates with the local economy. Data shows that union membership plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[/caption]

SEARCHING FOR A CAUSE

Cavazza, who’s also an adjunct professor at Roger Williams University School of Law, says the increased union activity shouldn’t come as a surprise “when you look at the current legal landscape and the economic instability” marked by sky-high inflation and the Great Resignation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, the administration of President Joe Biden is widely viewed as strongly supportive of unions, and progressive politicians have been outspoken in backing labor.

“You have a perfect storm for union organizing,” Cavazza said.

Loomis notes that the high cost of housing, along with the number of college graduates with student debt working at places such as cafes, has also fueled the movement.

“You have people coming out of places like [Johnson & Wales University] and Roger Williams and they’re not exactly stepping into great jobs,” Loomis said. “They figure they should have more and they’re trying to figure out how to get that.”

Chloe Chassaing says the rising calls for racial justice in the summer of 2020 also played a role.

[caption id="attachment_412468" align="alignleft" width="300"]

BOLD MOVE: Chloe Chassaing, a White Electric Coffee employee and member of the worker-owned cooperative that bought the business when it was put up for sale by the former owner after the employees formed an independent union.

PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

That’s when Chassaing and other employees at White Electric Coffee formed an independent union after writing a letter to the owner airing grievances, including the lack of employees of color. Amid tensions, the owner put the business up for sale, and it was bought by a worker-owned cooperative called CUPS Cooperative Inc. The business still operates as White Electric.

“People were kind of questioning existing structures, including their workplaces,” Chassaing said. “There was a spirit in the air with people ready and willing to put in the effort to make many aspects of their lives more sustainable and just. There’s more general societal agreement that all jobs should have some sort of dignity. That’s hopefully a baseline we’re all coming to agree on.”

Cavazza said several “nontraditional” industries, including legalized marijuana operations, have also faced union drives.

In April 2021, workers at the marijuana dispensary Greenleaf Compassionate Care Center Inc. in Portsmouth voted to join UFCW Local 328, then two months later held a one-day strike to protest the firing of one of the organizers. The worker was reinstated after an investigation by the NLRB.

Greenleaf did not return a message seeking comment.

Cavazza expects more attempts at unionizing workers in Rhode Island’s cannabis industry as it undergoes a rapid expansion with the legalized use and sale of recreational marijuana. “The grow operations in California and across the country are being hit with organizing activity at all levels,” he said.

UPPER HAND

So far, the Starbucks off Route 2 in Warwick remains the only one in Rhode Island to file for unionization.

Burke, one of the organizers, says she and her co-workers were motivated to protect job benefits, advocate for pay increases and address subpar working conditions, such as scheduling issues that have left workers short-staffed on certain shifts.

Laurie White, president of the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, says she believes this union movement will ebb eventually. For now, unionization efforts are in part an outgrowth of labor shortages that have given qualified workers the upper hand in the workplace. “The talent is ratcheting up the pressure on employers to prove [their company is] a good fit,” she said. Workers “are being more assertive.”

At the same time, White doesn’t see the recent unionization efforts as “organic,” but more about large labor organizations “trying to find areas where they can dip their toe in the water” now that the pandemic has altered workplaces and inflation is pushing the cost of living higher.

“There’s a more receptive workforce now,” White said.

That said, as many companies struggle to hire and retain qualified workers – what White calls “the No. 1 issue today” facing businesses – she says some unions could assist in alleviating some of those problems by providing a stable pipeline of trained workers.

“[Unionization] doesn’t have to be antagonistic,” White said.

FIGHTING ON: John Foley, a former employee at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick who reached out to employees about forming a union, has filed complaints with the National Labor Relations Board after the company informed Foley not to speak to Jay employees about unionizing.

PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY[/caption]

SELF-STARTERS

The efforts certainly inspired John Foley.

The 35-year-old Providence resident had been on the job as a supply chain and demand planner at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick for less than a year when he learned of the organizing activities at Starbucks and Amazon months ago.

Foley had never been affiliated with a union before, but he says it wasn’t long before he was reaching out to other employees about forming a union to demand better pay for new employees and to address other workplace frustrations.

“The real catalyst was seeing how my fellow co-workers dealt with what we’re dealing with day to day,” Foley said. “I had heard of Starbucks and Amazon unionizing. And if they could do it, we could do it.”

This type of independent initiative has much of the old guard of the union movement taking notice because it isn’t relying on experienced organizers from large, long-established labor groups to do the groundwork.

In the case of Starbucks, it started with a group of workers at a store in Buffalo, N.Y., voting to unionize in January and becoming the first Starbucks outlet represented by the Service Employees International Union-affiliated Workers United. Since then, workers at hundreds of other stores have filed to unionize, and similar actions have happened at places such as Amazon warehouses and Recreational Equipment Inc. – or REI – stores.

“This is self-started in many of these places,” said Scott Duhamel, secretary and treasurer for the Rhode Island Building and Construction Trades Council, a coalition of 16 craftsmen unions.

“No particular union has sought them out,” Duhamel said. “Traditionally, we’d have union representatives do visits, meet people at home or have everybody meet us off-site. This is certainly a new kind of movement.”

In some cases, Duhamel says, these independents seek assistance from well-established labor groups to help defray legal costs, and affiliations are formed that strengthen the overall union movement.

“We feel encouraged,” Duhamel said. “It’s been a long time since we’ve seen stuff like this.”

THE REACTION

Of course, not everybody’s happy about it.

For instance, Starbucks has fought against a union infiltration of its more than 15,000 U.S. stores and its CEO Howard D. Schultz has warned that unionization will prevent the multibillion-dollar company from implementing unilateral changes, including wage increases that were announced last year.

From the perspective of many business owners, union activities mean added costs and wasted time, and an added barrier between managers and their employees, says Timothy C. Cavazza, a management-side labor attorney at the Providence-based Whelan Corrente & Flanders LLP.

“It can be costly when dealing with contract negotiations every year or every three years, or when facing a strike that’s aimed at hitting production or affecting supply chains,” Cavazza said. “It’s the costs in terms of the legal fees and the consulting fees. It’s the management and supervisory time away, pulling people off an assembly line trying to get a product out the door, to engage in 12 hours of contract negotiations and trying to fill holes while workers are out striking.”

At Jay Packaging Group, Foley’s attempt to organize the workforce apparently didn’t go over well.

Foley says the company claimed he made statements indicating that he resigned from the job, but he denies that. Jay Packaging later offered him a severance agreement providing back pay and a small additional sum but refused to bring him back to work, Foley says.

Working with an organizer for Teamsters Local 251, Foley filed complaints with the NLRB accusing the company of unfair business practices when it informed other employees not to speak to him and told him he couldn’t contact colleagues to organize. Foley still hopes to be reinstated.

Jay Packaging did not respond to an email and a phone call seeking comment. But in a letter to Foley’s attorney, the company said it would not agree to bring Foley back, citing his “evident unhappiness” and questioning “why he would even want” to return.

Things have proceeded differently at Seven Stars Bakery.

Dozens of workers at the bakery’s five locations, in Providence, East Providence and Cranston, notified management by letter in mid-June that they were starting the unionization process, saying they were looking for better pay and benefits.

Days later, management had agreed to recognize the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 328 as the workers’ representative.

Co-owner Bill Daugherty declined to comment recently, saying both sides are “in a bit of a quiet period” as Local 328 gets “up to speed” before starting collective bargaining.

Cavazza says his workload has increased due to the recent rise in labor activism. His advice for companies: be proactive before finding themselves in the midst of a unionization campaign.

He also says it’s important for employers to remember “what not to do in these circumstances.” The NLRB states that employers may not discriminate in any way against a worker participating in union activities, such as threatening, interrogating, or spying on pro-union employees, or promising benefits if they drop unionization efforts.

“Try to keep employees happy and don’t give them a reason to seek out that representation,” Cavazza said. “Keep supervisors and managers trained on how to effectively respond when faced with this kind of activity. And just run a good business. Don’t derail everything simply because this activity is going on.”

[caption id="attachment_412470" align="alignright" width="300"]

FIGHTING ON: John Foley, a former employee at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick who reached out to employees about forming a union, has filed complaints with the National Labor Relations Board after the company informed Foley not to speak to Jay employees about unionizing.

PBN PHOTO/RUPERT WHITELEY[/caption]

SELF-STARTERS

The efforts certainly inspired John Foley.

The 35-year-old Providence resident had been on the job as a supply chain and demand planner at Jay Packaging Group Inc. in Warwick for less than a year when he learned of the organizing activities at Starbucks and Amazon months ago.

Foley had never been affiliated with a union before, but he says it wasn’t long before he was reaching out to other employees about forming a union to demand better pay for new employees and to address other workplace frustrations.

“The real catalyst was seeing how my fellow co-workers dealt with what we’re dealing with day to day,” Foley said. “I had heard of Starbucks and Amazon unionizing. And if they could do it, we could do it.”

This type of independent initiative has much of the old guard of the union movement taking notice because it isn’t relying on experienced organizers from large, long-established labor groups to do the groundwork.

In the case of Starbucks, it started with a group of workers at a store in Buffalo, N.Y., voting to unionize in January and becoming the first Starbucks outlet represented by the Service Employees International Union-affiliated Workers United. Since then, workers at hundreds of other stores have filed to unionize, and similar actions have happened at places such as Amazon warehouses and Recreational Equipment Inc. – or REI – stores.

“This is self-started in many of these places,” said Scott Duhamel, secretary and treasurer for the Rhode Island Building and Construction Trades Council, a coalition of 16 craftsmen unions.

“No particular union has sought them out,” Duhamel said. “Traditionally, we’d have union representatives do visits, meet people at home or have everybody meet us off-site. This is certainly a new kind of movement.”

In some cases, Duhamel says, these independents seek assistance from well-established labor groups to help defray legal costs, and affiliations are formed that strengthen the overall union movement.

“We feel encouraged,” Duhamel said. “It’s been a long time since we’ve seen stuff like this.”

THE REACTION

Of course, not everybody’s happy about it.

For instance, Starbucks has fought against a union infiltration of its more than 15,000 U.S. stores and its CEO Howard D. Schultz has warned that unionization will prevent the multibillion-dollar company from implementing unilateral changes, including wage increases that were announced last year.

From the perspective of many business owners, union activities mean added costs and wasted time, and an added barrier between managers and their employees, says Timothy C. Cavazza, a management-side labor attorney at the Providence-based Whelan Corrente & Flanders LLP.

“It can be costly when dealing with contract negotiations every year or every three years, or when facing a strike that’s aimed at hitting production or affecting supply chains,” Cavazza said. “It’s the costs in terms of the legal fees and the consulting fees. It’s the management and supervisory time away, pulling people off an assembly line trying to get a product out the door, to engage in 12 hours of contract negotiations and trying to fill holes while workers are out striking.”

At Jay Packaging Group, Foley’s attempt to organize the workforce apparently didn’t go over well.

Foley says the company claimed he made statements indicating that he resigned from the job, but he denies that. Jay Packaging later offered him a severance agreement providing back pay and a small additional sum but refused to bring him back to work, Foley says.

Working with an organizer for Teamsters Local 251, Foley filed complaints with the NLRB accusing the company of unfair business practices when it informed other employees not to speak to him and told him he couldn’t contact colleagues to organize. Foley still hopes to be reinstated.

Jay Packaging did not respond to an email and a phone call seeking comment. But in a letter to Foley’s attorney, the company said it would not agree to bring Foley back, citing his “evident unhappiness” and questioning “why he would even want” to return.

Things have proceeded differently at Seven Stars Bakery.

Dozens of workers at the bakery’s five locations, in Providence, East Providence and Cranston, notified management by letter in mid-June that they were starting the unionization process, saying they were looking for better pay and benefits.

Days later, management had agreed to recognize the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 328 as the workers’ representative.

Co-owner Bill Daugherty declined to comment recently, saying both sides are “in a bit of a quiet period” as Local 328 gets “up to speed” before starting collective bargaining.

Cavazza says his workload has increased due to the recent rise in labor activism. His advice for companies: be proactive before finding themselves in the midst of a unionization campaign.

He also says it’s important for employers to remember “what not to do in these circumstances.” The NLRB states that employers may not discriminate in any way against a worker participating in union activities, such as threatening, interrogating, or spying on pro-union employees, or promising benefits if they drop unionization efforts.

“Try to keep employees happy and don’t give them a reason to seek out that representation,” Cavazza said. “Keep supervisors and managers trained on how to effectively respond when faced with this kind of activity. And just run a good business. Don’t derail everything simply because this activity is going on.”

[caption id="attachment_412470" align="alignright" width="300"] Rhode Island has historically been one of the most unionized states in the country, but total union membership fluctuates with the local economy. Data shows that union membership plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[/caption]

SEARCHING FOR A CAUSE

Cavazza, who’s also an adjunct professor at Roger Williams University School of Law, says the increased union activity shouldn’t come as a surprise “when you look at the current legal landscape and the economic instability” marked by sky-high inflation and the Great Resignation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, the administration of President Joe Biden is widely viewed as strongly supportive of unions, and progressive politicians have been outspoken in backing labor.

“You have a perfect storm for union organizing,” Cavazza said.

Loomis notes that the high cost of housing, along with the number of college graduates with student debt working at places such as cafes, has also fueled the movement.

“You have people coming out of places like [Johnson & Wales University] and Roger Williams and they’re not exactly stepping into great jobs,” Loomis said. “They figure they should have more and they’re trying to figure out how to get that.”

Chloe Chassaing says the rising calls for racial justice in the summer of 2020 also played a role.

[caption id="attachment_412468" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Rhode Island has historically been one of the most unionized states in the country, but total union membership fluctuates with the local economy. Data shows that union membership plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[/caption]

SEARCHING FOR A CAUSE

Cavazza, who’s also an adjunct professor at Roger Williams University School of Law, says the increased union activity shouldn’t come as a surprise “when you look at the current legal landscape and the economic instability” marked by sky-high inflation and the Great Resignation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, the administration of President Joe Biden is widely viewed as strongly supportive of unions, and progressive politicians have been outspoken in backing labor.

“You have a perfect storm for union organizing,” Cavazza said.

Loomis notes that the high cost of housing, along with the number of college graduates with student debt working at places such as cafes, has also fueled the movement.

“You have people coming out of places like [Johnson & Wales University] and Roger Williams and they’re not exactly stepping into great jobs,” Loomis said. “They figure they should have more and they’re trying to figure out how to get that.”

Chloe Chassaing says the rising calls for racial justice in the summer of 2020 also played a role.

[caption id="attachment_412468" align="alignleft" width="300"] BOLD MOVE: Chloe Chassaing, a White Electric Coffee employee and member of the worker-owned cooperative that bought the business when it was put up for sale by the former owner after the employees formed an independent union.

PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

That’s when Chassaing and other employees at White Electric Coffee formed an independent union after writing a letter to the owner airing grievances, including the lack of employees of color. Amid tensions, the owner put the business up for sale, and it was bought by a worker-owned cooperative called CUPS Cooperative Inc. The business still operates as White Electric.

“People were kind of questioning existing structures, including their workplaces,” Chassaing said. “There was a spirit in the air with people ready and willing to put in the effort to make many aspects of their lives more sustainable and just. There’s more general societal agreement that all jobs should have some sort of dignity. That’s hopefully a baseline we’re all coming to agree on.”

Cavazza said several “nontraditional” industries, including legalized marijuana operations, have also faced union drives.

In April 2021, workers at the marijuana dispensary Greenleaf Compassionate Care Center Inc. in Portsmouth voted to join UFCW Local 328, then two months later held a one-day strike to protest the firing of one of the organizers. The worker was reinstated after an investigation by the NLRB.

Greenleaf did not return a message seeking comment.

Cavazza expects more attempts at unionizing workers in Rhode Island’s cannabis industry as it undergoes a rapid expansion with the legalized use and sale of recreational marijuana. “The grow operations in California and across the country are being hit with organizing activity at all levels,” he said.

UPPER HAND

So far, the Starbucks off Route 2 in Warwick remains the only one in Rhode Island to file for unionization.

Burke, one of the organizers, says she and her co-workers were motivated to protect job benefits, advocate for pay increases and address subpar working conditions, such as scheduling issues that have left workers short-staffed on certain shifts.

Laurie White, president of the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, says she believes this union movement will ebb eventually. For now, unionization efforts are in part an outgrowth of labor shortages that have given qualified workers the upper hand in the workplace. “The talent is ratcheting up the pressure on employers to prove [their company is] a good fit,” she said. Workers “are being more assertive.”

At the same time, White doesn’t see the recent unionization efforts as “organic,” but more about large labor organizations “trying to find areas where they can dip their toe in the water” now that the pandemic has altered workplaces and inflation is pushing the cost of living higher.

“There’s a more receptive workforce now,” White said.

That said, as many companies struggle to hire and retain qualified workers – what White calls “the No. 1 issue today” facing businesses – she says some unions could assist in alleviating some of those problems by providing a stable pipeline of trained workers.

“[Unionization] doesn’t have to be antagonistic,” White said.

BOLD MOVE: Chloe Chassaing, a White Electric Coffee employee and member of the worker-owned cooperative that bought the business when it was put up for sale by the former owner after the employees formed an independent union.

PBN PHOTO/MICHAEL SALERNO[/caption]

That’s when Chassaing and other employees at White Electric Coffee formed an independent union after writing a letter to the owner airing grievances, including the lack of employees of color. Amid tensions, the owner put the business up for sale, and it was bought by a worker-owned cooperative called CUPS Cooperative Inc. The business still operates as White Electric.

“People were kind of questioning existing structures, including their workplaces,” Chassaing said. “There was a spirit in the air with people ready and willing to put in the effort to make many aspects of their lives more sustainable and just. There’s more general societal agreement that all jobs should have some sort of dignity. That’s hopefully a baseline we’re all coming to agree on.”

Cavazza said several “nontraditional” industries, including legalized marijuana operations, have also faced union drives.

In April 2021, workers at the marijuana dispensary Greenleaf Compassionate Care Center Inc. in Portsmouth voted to join UFCW Local 328, then two months later held a one-day strike to protest the firing of one of the organizers. The worker was reinstated after an investigation by the NLRB.

Greenleaf did not return a message seeking comment.

Cavazza expects more attempts at unionizing workers in Rhode Island’s cannabis industry as it undergoes a rapid expansion with the legalized use and sale of recreational marijuana. “The grow operations in California and across the country are being hit with organizing activity at all levels,” he said.

UPPER HAND

So far, the Starbucks off Route 2 in Warwick remains the only one in Rhode Island to file for unionization.

Burke, one of the organizers, says she and her co-workers were motivated to protect job benefits, advocate for pay increases and address subpar working conditions, such as scheduling issues that have left workers short-staffed on certain shifts.

Laurie White, president of the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, says she believes this union movement will ebb eventually. For now, unionization efforts are in part an outgrowth of labor shortages that have given qualified workers the upper hand in the workplace. “The talent is ratcheting up the pressure on employers to prove [their company is] a good fit,” she said. Workers “are being more assertive.”

At the same time, White doesn’t see the recent unionization efforts as “organic,” but more about large labor organizations “trying to find areas where they can dip their toe in the water” now that the pandemic has altered workplaces and inflation is pushing the cost of living higher.

“There’s a more receptive workforce now,” White said.

That said, as many companies struggle to hire and retain qualified workers – what White calls “the No. 1 issue today” facing businesses – she says some unions could assist in alleviating some of those problems by providing a stable pipeline of trained workers.

“[Unionization] doesn’t have to be antagonistic,” White said.