Thomas Edison’s teacher said he was a bad student. His mother was angry at that characterization, took him out of school and taught him at home.

Edison gave this account of the incident in an interview published on Nov. 29, 1907: “One day I overheard the teacher tell the inspector that I was ‘addled,’ and it would not be worthwhile keeping me in school any longer. I was so hurt by this last straw that I burst out crying and went home and told my mother about it. Then I found out what a good thing a good mother is.

“She came out as my strong defender. ... She brought me back to school and angrily told the teacher that he didn’t know what he was talking about, that I had more brains than he himself and a lot more talk like that.

“In fact, she was the most enthusiastic champion a boy ever had, and I determined right then that I would be worthy of her and show her that her confidence was not misplaced.”

A positive word of encouragement can help change anyone’s destiny.

In many ways, Mrs. Edison was a genius herself, at least at motivating and encouraging her son. … She wasn’t going to risk limiting his potential the way his unfeeling teacher was willing to.

In the same vein, good managers have a responsibility to offer encouragement to workers to help them achieve at their maximum level.

Encouragement and motivation go hand in hand, but they are not the same. Motivation is more general – cheerleading, if you will, getting people excited and primed to take on or continue a project.

Encouragement means pointing out a person’s potential and challenging him or her to succeed at a specific goal or project. Encouragement means empowerment, according to Samir Nurmohamed, an assistant professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

“On the one hand, we know from research that people are much better at work when they feel empowered,” he told Entrepreneur magazine, “which consists of having meaning on the job, a sense of autonomy, a sense of confidence and also an impact on what you do and the people you’re trying to help.

“Yet you don’t want to feel so autonomous that you have no direction,” he continued. “It’s one thing to feel autonomous in terms of your motivation, but it’s another to be autonomous and go in the wrong direction.”

Top managers understand these basic truths about employee encouragement and motivation:

•

“I want to feel important.” No one wants to feel like a number, interchangeable or easy to forget. Get to know your employees as people. And show them you’re paying attention to their individuality.

•

“I need encouragement.” Let your employees know what they’re doing right and how they can keep performing at a high level.

•

“I want to believe in you.” Employees want to know they can trust you – your knowledge, your expertise and your word. Show that you are committed to helping them succeed and grow by listening, answering questions honestly and keeping your promises.

•

“I want to succeed.” Most employees want to do a good job, even if they don’t want to advance to upper management. Explain your expectations clearly and give them the training and support they need so they know you’re invested in helping them succeed.

•

“I want to be motivated.” Employees want to be clear about the job’s value to the organization, the benefits the employee will enjoy. Encouragement enhances enthusiasm and commitment.

Hall of Fame ballplayer Reggie Jackson put it in baseball terms, but I think it applies across the board: “A great manager has a knack for making ballplayers think they are better than they think they are. He forces you to have a good opinion of yourself. He lets you know he believes in you. He makes you get more out of yourself. And once you learn how great you really are, you never settle for playing less than your very best.”

Mackay’s Moral: Encouragement gives you the courage to try.

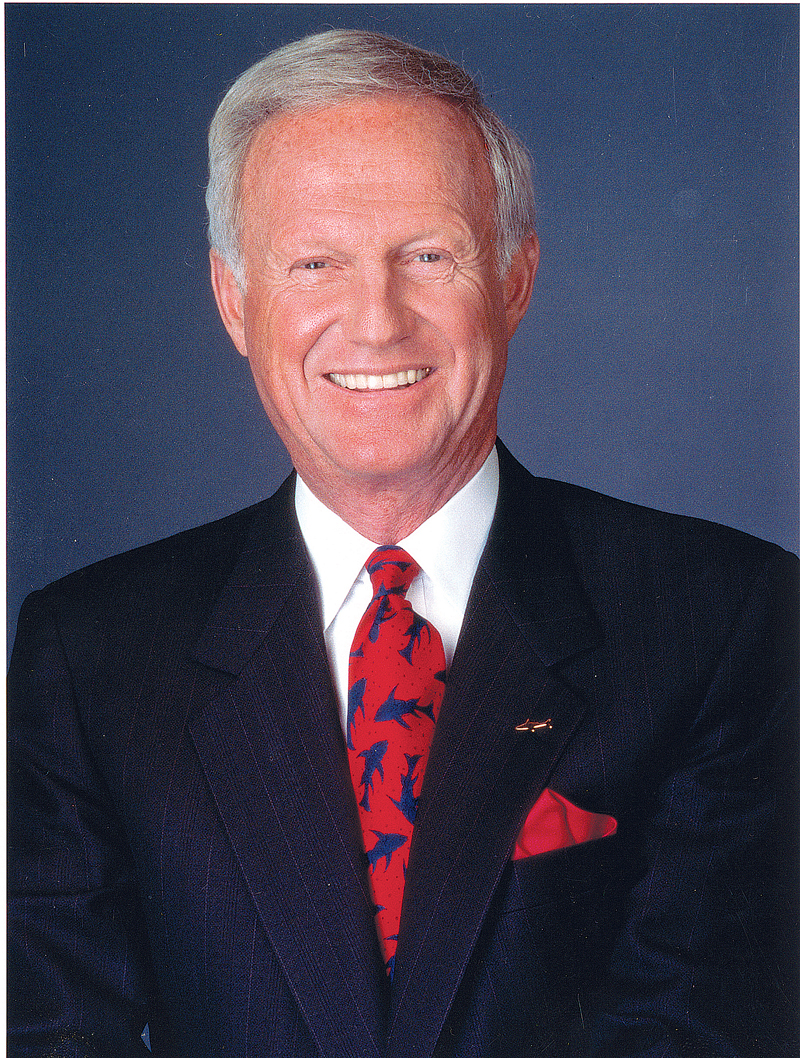

Harvey Mackay is the author of the New York Times best-seller “Swim With the Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive.” He can be reached through his website, www.harveymackay.com.