Safety measure to cost medicine companies

In order to prevent more deaths due to medication errors, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is in the process of mandating bar codes on all packaging for human drugs and biological products.

The undertaking would mean an increase in cost for manufacturers and re-packagers who would now have to include a bar code on individual unit packages that include a product’s National Drug Code number or NDC. The NDC would help identify the manufacturer and the drug. Additional information including expiration date and lot number might also be part of the mandate.

In December 2001, the FDA proposed the rule to use a bar code that, when used in conjunction with bar code scanners and computer equipment, will help reduce the number of medication errors.

The announcement came after a 1999 report by the Institute of Medicine, which reported that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans die each year due to medical mistakes made by health care professionals, with nearly 7,000 deaths attributable to medication errors.

Because of the high number of deaths related to medication errors, the FDA plans to speak about the status of the FDA bar cod initiative, at the Bar Cod Implementations Strategies Conference later this month. Industry experts say the FDA was rumored to release the guidelines in mid-February, but never did.

Pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and biotech businesses are expected to gather to find out how this new rule will affect them.

Some of those groups include Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer.

Bar coding technology is likely to reduce the incidence of errors at the first stage of the medication use system, the system of administering drugs.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices, a Pennsylvania-based non-profit organization that works to provide education about adverse drug events and prevention, states that the reduction in errors using the technology occur in acute-care facilities such as hospitals.

In an acute-care setting, a medical professional would scan his or her identification badge. The professional would then scan the patient’s identification and the drug’s bar-coded label with a bar code scanner.

If there were a discrepancy between the patient, the patient’s medication record, and the drug packaging it would trigger a warning to the medical professional to investigate the mismatch before administering the medication.

If the regulation requires bar coding to the unit dose level with the NDC only, then there will be little cause for package modification, according to the FDA.

If the initial recommendation, however, requires more data than the NDC, then both the current and future packaging and processes may be affected.

Ultimately, it is the manufacturers that will be impacted the most.

Manufacturers will have to create unit-dose packaging because label space will become “more restrictive and cost issues prohibitive,” according to the FDA. A unit dose is a single dose taken by a patient at a specific time. Institutions will need the individual dosages or “blisters” in order to disperse them to patients.

Hospitals don’t have enough pharmacists to count out the drugs and disperse them to patients, so institutions rely heavily on unit dose packaging.

Although the cost to moving to such a system would be high – between $500 million and $1.4 billion over 10 years – the cost associated with such medication errors is higher.

Costs of preventable drug-related mortality exceed $177.4 billion annually, according to some industry reports. Hospital admissions accounted for $121.5 billion and long-term care admissions accounted for $32.8 billion.

This is why several pharmaceutical companies have jumped on the bandwagon, despite the cost associated with the change.

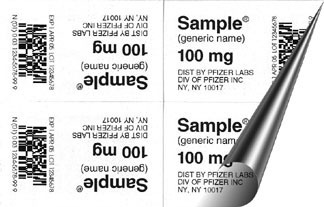

In January, Pfizer Inc., a New York-based pharmaceutical giant with offices in Connecticut and Massachusetts, said it would begin using bar code technology on its hospital unit dose products in an effort to decrease errors at hospitals and pharmacies.

Pfizer’s new bar code system, developed to fall under Reduced Space Symbology standards, a standard formed under the Uniform Code Council, will allow for each Pfizer unit to include the NDC, expiration date and lot number in both machine readable formats and human readable formats.

Pfizer’s 31 blister products will have the new bar codes by the end of the year.

Byron Bond, director of trade operations and customer service at Pfizer Pharmaceutical Group, said Pfizer was the first to introduce the bar codes – without any FDA regulations stipulating it do so.

“Hospitals were saying that the technology was out there, but no one has jumped on,” Bond said. “We too fell into the trap of saying there aren’t any regulations, no guidelines and no one is using them.

“We kind of felt that it was the right thing to do,” he said.

Putting the bar codes on is a major technological challenge, Bond said, but once Pfizer figured out how to do it – it wasn’t as costly as originally anticipated.

“We do it with off-the-shelf technology,” Bond said. “We used existing, old printing equipment because you can’t go out there and require capital investments of millions of dollars.

“Our capital investment was almost zero — that’s because we had good vendors.”

Time is one thing, but degree of difficulty is another.

Pfizer’s Bond said placing NDC on a unit dose package is only 80 percent of the solution.

“If you are just going to do the NDC on the bar code, that’s a piece of cake,” he said.

When you look at vaccines and biologicals, lot numbers and expiration dates become “critical,” according to Bond.

“Lot number and expiration dates become difficult because you have to do that on the production line and print at a high speed. You have to make sure that you verify it.”

Pfizer is hoping that its peers are on board and hope they move in the same direction when it comes to bar coding. Abbot Laboratories and Merck & Company are moving forward in its efforts in including bar codes.

Amgen, a California-based pharmaceutical giant, which has a manufacturing facility in West Greenwich, did not return calls made to its corporate office to discuss bar coding.

Some manufacturers, in order to avoid such regulations, will produce in bulk, say many experts including the FDA.

If individual manufacturers don’t adhere to the rules and instead produce the products in bulk, they run the risk of losing business to third-party businesses, according to Bond. Third-party businesses will see an opportunity to sell into the institutions by buying the product off the market, adding a NDC code, repackaging and reselling it.

“That will only hurt manufacturers, because there is a strong demand for blister

unit dosages,” said Bond.

For the complete current issue, visit our subscription Web site, or call (401) 273-2201, ext. 227 or 234.